The buzz surrounding AI-generated art is getting louder and louder; new thinkpieces come out on the regular, mostly orbiting around the question of whether or not AI will replace human artists. The takes range from “no big deal” to “existential crisis”: the Oxford Internet Institute released an 80-page paper arguing that we don’t need to be worried, but Erik Hoel is very concerned about AI replacing creators, considers AI “an affront to human dignity”, and wonders if it might be time for a Dune-style war against AI research. The editorial board here at RUINS tasked me with evaluating how AI art generators correspond with the parameters of traditional artistic practice. Here’s what I came up with. But first, let’s define the playing field a little bit.

There are many kinds of AI art generators on the internet, but the text-prompt generators are getting the most notice, with Wombo, Night Café, and Hotpot leading the pack. Lurking in the background is DALL·E, which hasn’t yet been released to the general public but which is causing some serious head-turning on Twitter and Instagram.1

The open-to-the-masses text-prompt AI art generators can reliably produce swirls of pretty colors and interesting patterns, similar to what you would expect to see in a hospital corridor or a bank lobby. So far, so good—unless you work as an artist creating such images, in which case your livelihood might become uncertain.2 But what else can AI art generators do? What can’t they do?

Well . . . I’ve been trying very hard to get Wombo to scare me, and it can’t do it. When I type in “frightening monster” or something like that, I reliably get an image that looks more like an animal than it doesn’t, occasionally with traces of eyes, teeth, or fur. Some of the images it gives me have the same feel as certain paintings by Max Ernst, such as The Triumph of Surrealism.

However, the Ernst painting relies on its internal composition for much of its expressive power. Ernst’s monster is stomping around, roaring, and waving its arms; Wombo’s monsters don’t have the anatomy necessary to look menacing in the same way. That’s too bad, because if AI art is going to be the next big new thing, it will have to be able to be disturbing. Monsters and other frightening and creepy imagery have been a staple of artistic expression for centuries, from the enormous prisons of Piranesi to Saturn Devouring His Children to Grateful Garfield, the Engorged. AI art just can’t do that kind of scary.

What’s even harder to produce than scary art is beautiful art. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, as they say; what I might think is beautiful might not be beautiful to the next person. Yet the AI can’t deal with abstractions like “beautiful”; it has been trained to recognize and duplicate imagery of a more concrete kind. I can get an AI to make images that are reliably “beautiful” in the sense of having intriguing textures and pleasant colors, or even things like flowers and sunsets; but it is a very randomized, clichéd, lowest-common-denominator type of beauty: “we’ll put flowers in there because everyone thinks flowers are beautiful”, etc. Just like scary art, beautiful art requires a sense of composition. The sense of space, rhythm, and drama in such paintings as, for example, Millais’ Lorenzo and Isabella or Vermeer’s The Art of Painting or even Thomas Kinkade’s Candlelight Cottage is something that AI can’t yet do. When I tried to get Night Café to create a beautiful image, it just got confused.

The most formidable obstacle to AI art being useful in the artist’s toolkit is that it lacks the ability to effectively communicate. The swirling, slightly blurry, nondescript images are profoundly intriguing, but only in an “interesting” way: there is no real communication going on. A human artist has, by definition, thoughts and feelings that can be expressed in their art; an AI, by definition, does not.

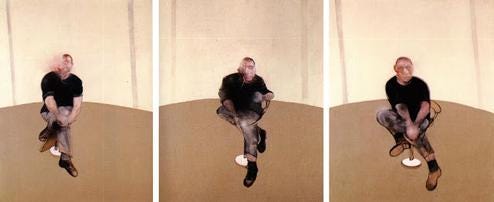

Consider this Francis Bacon self-portrait.

Of his self-portraits, Bacon was fond of saying things like “people have been dying around me like flies and I've had nobody else to paint but myself . . . I loathe my own face, and I've done self-portraits because I've had nothing else to do” and “One of the nicest things Jean Cocteau said was ‘each day in the mirror I watch death at work.’ That is what one does to oneself.”3

The style of Bacon’s self-portraits is highly reminiscent of the distorted, smeared renderings produced when an AI is commanded to make a portrait. But the difference is that, when we look at a Bacon self-portrait, we can appreciate the anguish of soul that motivated him to express himself in that way, to distort his own features and blur them into near-unrecognizability. Francis Bacon is speaking a language, and was able to use the medium of paint to relay his feelings and ideas. Does Night Café do that? I’m afraid not. We know, objectively, that there is no conscious choice-making behind the smeariness in an AI image. If it looks like it might be communicating something—if an AI portrait’s blurriness makes us think about mortality and self-loathing the way Bacon’s blurriness does—we can be assured that we, and we alone, are bringing that to the AI artwork. This is certainly an appropriate response to the AI artwork; but we ought to harbor no illusions about its significance.

Some people have expressed concern about the inherent biases revealed by AI art generators. Joseph Schneider entered prompts of traditionally male names into Wombo, and got pictures of faces; when he entered female names, he got images of bodies, many of them implicitly sexualized. Fawzi Ammache, is his excellent write-up of DALL·E, points out that the program “defaults to Western culture, customs, and traditions when generating images of things like weddings, restaurants, and homes.”

But the bias isn’t the fault of the AI. What they are doing is reflecting the biases inside of ourselves. The AI will only ever show us our preconceptions of how things ought to appear; an image from an AI art generator will “look just like” something only because that is what we expect the thing to look like. Consider this image by DALL·E, generated using a prompt of “Antique photo of a knight riding a T-Rex.”

Does this look realistic? I hope you didn’t say yes. No one has ever seen a live T-Rex, let alone one with a knight4 riding it. So how do you know what it would look like? What if I try to get the AI to show me something that would be impossible to visualize, such as “men’s fashion in 500 years”?

Imagine you are a professional artist, and you have been invited to produce a work for an exhibition centered around a specific theme—such as, for example, last year's show at Omaha's Bemis Gallery organized around the idea of empathy. Your method of work will probably be to break out your notebook and start brainstorming. Once you have some good ideas, you start sketching or otherwise filling out the concept. Once you have something promising, you go into the studio and start making art; maybe you're a painter so you start painting—but maybe you're a maker of video installations, or you work with textiles—I don't know, but you start making art.

Eventually, you will have a piece that you think is finished. It expresses what you want to say, and it does it in an artistic fashion; elements of your own personality and style are inherent in the work, and there might be ambiguities in the piece, prompting the viewer to puzzle over the meaning, and bring something of themselves to the artwork. Perhaps there is more than one meaning implied in the piece, and it will act as a catalyst for discussion and further reflection by the gallery patrons. You are pleased with your work, and you send it on to the gallery or museum with a satisfied feeling of accomplishment.

What happens when you work with an AI art generator to produce your piece? You would have to start with a description of the finished piece—and the more detailed, the better. Then, you would start pounding that text description into the AI, and saving the results. Perhaps you accumulate twenty images corresponding to your prompt; you would them evaluate them and pick the one you like the most.

This isn't artistic practice—this is curatorial practice. Of course, good curating is an art of its own, but that verges into Seth Godin-style, “everything is art” territory, and we won't cover that here (although it is a good point, and worthy of discussion). I strongly doubt that an AI would ever produce something like Stephanie Syjuco’s I AM AN . . . (the first piece visible when you click on the Bemis show link above). Syjuco’s piece has all that the AI can’t give: ambiguity, multivalence, and a sense of the artist’s concerns and preoccupations. You might personally dislike it, but you can’t deny that it is a work of art with a definite purpose, significance, and expressive power. I am not convinced that AI can do those things . . . yet.

If you want to play around with some of the other kinds, you might be intrigued by Artbreeder, which takes two preexisting images and mingles them together to create a third image. or Generated Photos, which creates very realistic pictures of faces.

Or maybe not—maybe your job might become much easier.

I got these quotes from the Wikipedia article about this painting.

More like a jockey? Or a master of hounds?