Notes from what I guess counts as the bleeding edge of artistic possibility these days

Please tell me I’m not the only person who has a hard time staying abreast of what’s going on in the AI art space?! I can’t keep up—I just can’t keep up! Events transpire at a dizzying rate! The models continue to be calibrated and refined by the techno-wizards down in Silicon Valley, in pursuit, apparently, of the ever-unrealizable but nearly-within-reach goal of replacing all human activity with stuff done by robots. Previously on this blog I ranted about their lack of ability to draw human hands; that problem has been solved. I questioned their ability to produce truly disturbing and horrifying imagery; that goal has been accomplished too. AI images are now winning awards in photography contests, as we will see later in this essay. Charles Babbage was criticized for his word choice when he said of his difference engine that it was able to “know” the answer to a math problem; but it certainly does seem that the latest cohort of AI models is able to “interpret” text prompts and, crucially, to “imagine” the outcome when making a drawing or image. What should we think of all this?

Some readers may recall the AI project I did a while back—a set of illustrations complementing the spoken-word lyrics to Radiohead’s song “Fitter Happier” from OK Computer. For the original project I used the Nightcafé AI image generator’s “Artistic” model. However, this was back in August of 2022; with all the new developments it feels to me that an update is in order. What would be the result of revisiting the project using the new level of AI image generation capability? Let’s find out.

Unfortunately, Nightcafé’s “Artistic” model is no longer supported by the site’s current interface. So I had to use one of their newer models. Here’s the result of running the first line of the song—Fitter happier more productive—through some of Nightcafé’s popular models.

So we can see a few things here. SDXL 1.0 gives me what looks like some sort of generic “Better Workers!!!” motivational graphic with some Wes Anderson-esque knolling going on; yuck. Very corporate. I suppose this would fit in with Radiohead’s bitingly satirical song and the general level of satire found throughout OK Computer, but I don’t think the satire in the image is as self-conscious or tragically devastating as in the music. Next we have two renderings which are mere gobbeldegouk. I’ve noticed that many of the newer generation of AI image generators will, when fed a prompt they can’t assimilate, just give up and try to render the text as text. That’s what seems to be happening with Juggernaut XL v5, which is advertised by Nightcafé as being “an SDXL model for perfect realism and cinematic styles.” Well. Okay. Mysterious XL v4 is, according to Nightcafé, “an SDXL model for fantasy art and Asian culture.” Huh. It looks to me like a level from one of those old 2D platformer games like Commander Keen or Mario—oh hey, Mario is a product of Asian culture; I see the connection now! I have no idea what is going on with the image given to me by DreamShaper v8. The AI apparently latched onto the word “happier” and gave me a picture of a person smiling—but it seems to be the kind of hotel-front-desk, airline-flight-attendant smile of a person who is paid to be friendly. Hmm.

Let’s try the next line of the song—“Comfortable”—using the same models in the same order.

Hey Nightcafé: why can’t men be shown as being “comfortable?” Why do I only get girls or pets or empty beds? Are you biased, or what??

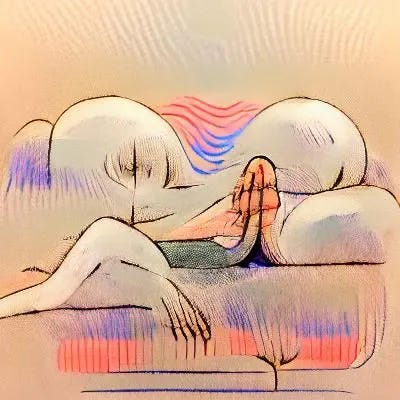

These images are utterly boring. Compare the result I got back in ‘22 when I ran the same text prompt into Nightcafé’s old “artistic” model:

It looks vaguely like a couch (“comfortable”) but it is otherwise very . . . weird . . . like a cubist couch or a Chagall couch or even a Max Ernst couch. This image is rather interesting; it means nothing, and so can mean anything. Like much of the abstract art of the twentieth century, it is open to interpretation and thus has the potential to be full of powerful significance for anyone who wishes to seriously ponder and contemplate it for an extended period of time. It has a pleasantly varied yet cohesive color palette (not the bland, Instagram-ready spectrum of grays and beiges that the current AI models gave me), and its sense of the picture plane is more “painterly” than the illusionistic three-dimensional spaces found in Nightcafé’s newer offerings. It is a beautiful image, in its own way. Isn’t that what we want in our images? Artistry? Why, then, are the newer generation of AI models not being artistic? That is a profoundly important question and I’ll get back to it in a moment.

Just for fun, I ran the entire series of text prompts from my earlier “Fitter, Happier, Illustrated” artist project into the Bing AI image creator. This AI is powered by DALLE3, the latest iteration of OpenAI’s signature product.1 The outputs of the Bing DALLE3 image engine are indeed impressive; the images it creates are full of realistic detail and it is capable of replicating a wide array of illustration styles and types. If you want to look at the series, here is a link to the entire collection of imagery.

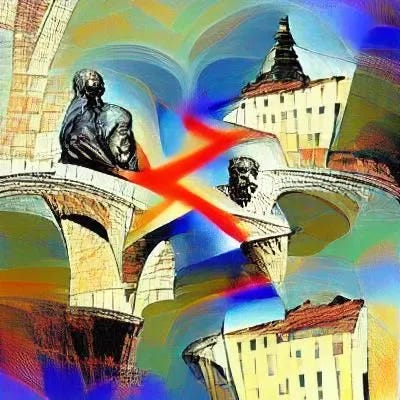

If you scroll through there, though, you’ll notice a few disheartening trends. The images are all very stereotypical and formulaic; it’s as if the AI looked up the lyrics to OK Computer, found the line “No surprises please” in the album’s tenth track, and complied. Compare the bizarre, strange, and uncanny stuff Nightcafé was giving me and you’ll immediately detect the difference (in the examples below, the Nightcafé image is on the left, the Bing image is on the right):

These drawings / photos are technically proficient, but they conform to stylistic expectations a bit too much for my liking. Look at how Nightcafé interpreted the text prompt “At ease” in a very vague, abstract, gestural way—and how Bing just went straight for the lowest-common-denominator “relaxing plus military terminology,” as if I had been playing a guessing game and it was supposed to provide an image which checked all the boxes. No alarms and no surprises, please! “Pragmatism not idealism” was taken by Nightcafé as a jumping-off point for another abstract assemblage of forms, colors, and lines, similar to some of Kandinsky’s best canvases; Bing apparently thought “those words sound like words from a motivational poster” and made one for me (by the way, the misspellings that all the image generators produce are simultaneously the next major hurdle these things will need to overcome, and outrageously funny sometimes). “The ability to laugh at weakness” was rendered by Nightcafé as a person with a slightly disturbing manic grin with apparently four jaws’ worth of clenched teeth? Bing puzzles over the phrase and wonders where it might potentially be used: “Maybe it’s from a self-help article in a magazine, one about making light of one’s personal problems? What kind of illustration might be in that article?” and then slavishly copies the art style such a magazine article might employ. With misspellings, of course.

DALLE3 can produce images of astoundingly diverse styles and kinds. At first this might seem like a good thing; isn’t it good that we are able to produce so many different kinds of illustrations? Certainly in a human artist, the ability to be versatile would be an asset. But the best artists seem to be the ones who get fixated on a small handful of very specific artistic problems and attend to them with meticulous focus, thereby producing an easily recognized, signature style. Even in the field of commercial illustration the best practitioners commonly cultivate a personal style. Consider Roz Chast; she has been cranking out cartoons for The New Yorker in exactly the same style for more than forty years. The history of commercial illustration stretches all the way back from Mary Engelbreit to Norman Rockwell to Charles Dana Gibson to Albrecht Dürer—and all of these people, and many more besides, are known as much for their signature style as for their typical subject matter. Despite not being part of the high tradition of art, illustrators are able to express their unique outlook on life through how they style their work. Why, then, would we want something that can merely ape the already established stylistic conventions? Don’t we want something that can be original? When we use AI to make an image, what do we want? This is another very important point, and we will return to it later.

While I was working with Bing’s AI image engine I noticed some strange things about how the site is talking about itself and about images in general.

This popped up after I made my first image. I interpret it as some kind of a disclaimer protecting Bing from angry users who didn’t get precisely what they wanted out of the AI-experience. But notice how the copywriters at Bing are framing the process of creation itself; they seem to be equating the creative act with the inspirational act, or at least with the creative act as practiced by members of the surrealist school. I know of numerous painters who would most certainly not have accepted “surprises” as part of the creative process. Whistler would rehearse his paintings, employing multiple sittings until he was confident of his ability to dash off the entire painting in one go. I’m fairly certain that the mid-twentieth-century photorealists, or the academics such as Gérôme, would not have been willing to let “surprises” get in the way of the exact duplication of the scene in front of them, or of the historical moment they were recreating. There is a difference between creativity and creation; the difference expressed in the old adage “write drunk, edit sober” or between the brainstorming and the final product. In inspiration mode, of course surprises are welcome. But the majority of artists would have been disappointed if they could not reliably get what was in their head onto the canvas.

During the image rendering process Bing showed me some placeholder “tips” (because people can’t be expected to do anything except watch that status bar; it’s inconceivable that they would do something like look out the window while the Microsoft robot slave is creating the image). Here is one of them.

Um, doesn’t exist? What, Bing, do you mean by that? The image does exist, in my mind, if I can describe it. That strikes me as really weird language to express the concept of “an image of something that is not possible in the real world”—but wait a minute, none of the great paintings ever described “the real world” in the way that Bing seems to be implying. I don’t need no AI image generator to give me Botticelli’s Birth of Venus or Goya’s Witches’ Sabbath or Dalí’s Premonitions of Civil War. Your regular ordinary human artist can do “doesn’t exist” just fine. Here’s another:

Hey Bing, could you describe an artist’s style to me? Could you, for instance, describe Van Gogh’s style?

“Sure. Van Gogh’s style looks like the paintings Van Gogh made.”

Huh! That’s quite a tautology there! I don’t know—maybe I’m just being cantankerous here, quibbling about the meaning of words, and allowing my disdain for the image engines to carry into a general nitpickiness regarding the way Microsoft is talking about the mechanics of how they work. However, the whole thing seems to betray a strangely warped idea of how art works, and what its place is in the broader society. Van Gogh is not a “brand” or “product”—his style is not “Van Gogh style” in the sense that it seems Microsoft is interpreting it to be. Look, I don’t know much at all about the culture or mindset or worldview of the people who are making and handling the Bing AI Image creator. Do they, in fact, look at a Van Gogh and think “this painting moves me in a certain way?” Or do they think “Van Gogh—okay, got it. Pattern has been recognized. I can use my familiarity with Van Gogh and map it onto the rest of the world, looking for shortcuts to understanding when I see other images.”

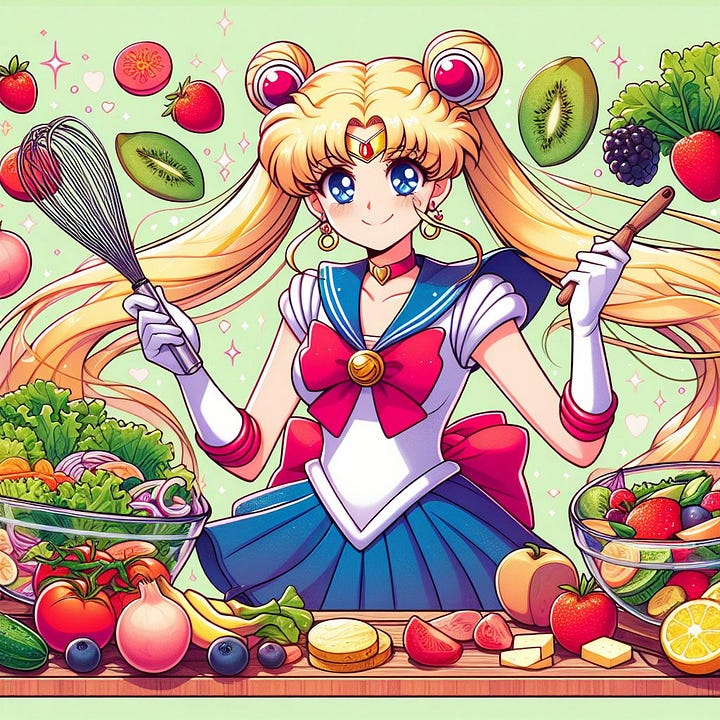

Towards the beginning of this essay I said that the AI image engines seem to be able to “imagine.” They aren’t just cobbling together a set of symbols in the way a child will draw symbols for houses, trees, etc. and present the result as a finished landscape; it’s almost as if the AI engines are thinking about composition, form, and line the way a real artist would. In an earlier essay I documented how the previous instantiations of AI were making images in the symbol-based way; as an example I described my unsuccessful attempts to get the various AI models to do a picture of Sailor Moon making a salad. Well . . the image generators are fully capable of jumping that hurdle too. Here is the Bing AI rendering that image:2

Here is Nightcafé doing the same thing:

They got it. Congratulations. I give up; there’s nothing I can say about these images other than they did it. Hooray! (I do really think it’s funny how Nightcafé’s Never Ending Dream model did Sailor Moon coming out of the salad. I imagine this as the logo on the menus of the salad shop Sailor Moon opened after she was done fighting crime or whatever it is that she does in the show, which I have never actually watched.)

But how does all of this compare to how an actual artist creates based on a text prompt?

In a fascinating discussion of his own creative process, reveals the way he responds to what amounts to a very, very long text prompt—the text of an essay for which he has been commissioned to provide the hero image. Naughton works with digital tools but he also uses—and loves—the process of drawing with a pencil or pen and painting with acrylics, as he affectionately describes:

What you don’t get from a digital drawing is this; the familiar smell of paint, the physical evidence on your hands, the jangle of water jugs as you clean the brush, the time away from a screen and a physical piece of artwork I can put on my wall immediately. Proof that an AI didn’t do it.

That last point—proof that an AI didn’t do it—is vital to Naughton’s idea of the whole point of art-making: it facilitates communication between people. By now it should be obvious that very little is being communicated when an AI image engine spits out a picture; at least, nothing more is being communicated than if I come back from the forest with a cool stick and tell people “look at this cool stick I found!” There is no process, no struggling past the challenges inherent in the medium, no fretting over mistakes, none of this:

Ink trace the pencil drawing on the lightbox—ok. It’s good, it will work but it’s total shit derivative crap, no it’s good, light hearted, hits the point accurately, but just lazy, sloppy illustration, archetypes and clichés, no, actually I like it . . . blah blah blah on and on until I finished it.

By creating a piece of art, Naughton—and every other human artist—opens himself up to failure. There is an aspect of vulnerability inherent in making art, just as there is with all other forms of communication; the art might not get the point across, it might not turn out right, it might be too emotionally demanding to finish, etc., etc. But there is nothing wrong with that; all the vulnerability and uncertainty and worry—and triumph, when it goes well—is part of what it means to be a human artist in the world. No AI art generator can feel those things; no AI art generator is capable of taking risks. When comparing machine-made art with art made by a human intellect, the end results might be extremely similar but the process and the motivation—the meaning—just won’t be there.

Something Naughton did not discuss in his essay was his opinion on the difference between art and illustration. The two disciplines obviously have an enormous amount of bleed-over and overlap, but are still distinct in the popular conception. The very phrase “art and illustration” implies some sort of separation between the two. Often an illustration will be accepted as fine art (for example the illustrations Aubrey Beardsley made for Oscar Wilde’s Salome); Also often (despite the howlings of the critics who insist on yelling “kitsch!”) is when fine art is used for illustrative purposes. Up to this point I’ve thought of the AI image engines as providing illustrations; this is how they seem to be used in most places where I find them (such as in this Dark Academia style guide). But can the AI art generators approach the level of fine art? A curious and intriguing thing recently happened on that very front: the German photographer Boris Eldagsen recently entered some AI-generated images in Sony’s World Photography Awards competition—and won, despite the competition’s organizers knowing that his images were made by AI.3 If these images are so valuable as art that they are winning competitions, what more is left? Are there any other frontiers for AI-generated imagery to cross?

From the very start I’ve been optimistic about the artists’ ability to figure out what to do with these AI generators. It seems Eldagsen has done just that: his images are, indeed, fascinating and evocative, full of ambiguity and a suppressed, oblique narrative sense—exactly what we would want from a good piece of art. These images bear a strong resemblance to the images from the early days of photography; they also have the same mood and tone as some of the photos by the surrealists, especially the work of Man Ray.

I’m still convinced that the best uses of the AI engines will come as an extension of the methods of the surrealists. The surrealists were always looking for ways to tap into their subconscious—to dredge up imagery which they did not, until then, knew existed. They would employ randomizers such as frottage (rubbing crayon or graphite over a surface to see what patterns and shapes would emerge) or they would stick paint between two canvases and pull them apart to see what happens (this is the method employed with great effect in Max Ernst’s painting Europe After the Rain II). They invented the “exquisite corpse” game as another randomizer. The AI image generators are splendidly appropriate for this kind of surrealist practice.

Which is why I’m somewhat disappointed in the apparent drive by the creators themselves for more realism, more precision, more clarity and less spontaneity in the new crop of image generators. The new models on Nightcafé have a very hard time doing purely strange and difficult-to-categorize imagery.

In the introduction to my original post from August 2022, I said that

the images have absolutely no coherent sense of style or visual aesthetic; this was not my intent. Unlike something such as Goya’s Disasters of War, which is obviously the work of only one artist, the AI images here are all over the place. What does this mean for an artist working with AI to produce art? Is it possible for an artist to have a coherent “AI style” of their very own?

Now that I look back, though, I have to disagree with my earlier self—what Nightcafé gave me was in fact a distinct visual style with recognizable attributes: blurriness coupled with sharp edges, vagueness in the details, a more-or-less shallow picture plane, allusions or gestures toward recognizable objects while remaining far afield of any direct visual description of anything. This is the “AI style” which we deserve, and which could have been used to stupendous effect if only the image generators hadn’t been tweaked away from spontaneity and randomness and towards predictable results.

Either the AI is meant to supplement human creativity, or to replace it. There’s no third option; either AI images will be used to aid or facilitate the activities of artists who are currently working in the field of art and illustration, or they won’t. We are at a point where two paths diverge, and it makes all the difference which one we take: now is the time to decide where we are going as a culture with these things, and as part of that decision-making process there are some serious questions we must ask ourselves.

If AI is meant to replace human creativity, then I think the whole enterprise is a worthless waste and ought to be opposed at every possible turn. There are many, many kinds of work which are eminently suited for relegation to robots because they are drudgery, or they are dangerous. Looking at Lewis Hine’s photographs of eight-year-old children tending cotton mills (with the constant threat of dismemberment or death as a normal part of the workday) makes me very glad we have robots to do that kind of work. I have personally seen the direct effects of serious industrial accidents; some jobs are simply too dangerous not to try to get them offloaded to machines. And I would much rather use a vacuum to clean the rugs in my house than to have to drag them outside and beat them with a stick until they were clean. Machines serve their highest purpose when they are used as aids to human flourishing in this manner, when they are used to eliminate the more odious or harmful kinds of work.

But work, on its own, is not evil. In the Bible, Adam and Eve were placed in the garden and given work to do before sin entered the story. Work can be immensely fulfilling and rewarding; it can connect people to the rest of global culture and give them a sense of purpose and meaning. It can provide security and it can allow human ingenuity to flourish in service of society-enriching goals. I shouldn’t have to convince anyone of these points! And creative work—writing, painting, drawing—has long been held to be the pinnacle of human expressive capability.

Why would we, as a society, be working toward replacing our uniquely human ability to express ourselves artistically . . . with the same thing done by a robot?

But suppose the alternative is indeed the case. Suppose that the AI image generators are really meant, not as a replacement for human creativity, but as a supplement to it. Perhaps the best use of the Bing AIs, the DALLEs, the Midjourneys, is to provide human artists with an additional tool in their kit—maybe in the way I described earlier as a randomizer. After all, the workings of the AI are more or less inscrutable to anyone working with them; it really does approach the status of another mind.

If it is true that artificial intelligence is another mind . . . why are we trying so hard to get that other mind to be just like us, to see the world and understand language in exactly the way we see it? Haven’t we watched enough science fiction films to know that the aliens can teach us new things because their minds are different? If so, why have we apparently given up on the chance to see the world as the computers see it? Why are the AI image generators being deliberately trained to give us the most banal kinds of imagery out there, the kinds we tend to forget as soon as we see them—motivational posters, road signs, logos, advertisements? Why is the bleeding edge of artistic possibility being purposely designed to be . . . boring??

If you recall, the precursor, DALLE2, was said by its inventors to be too powerful and potentially dangerous to be used by the general public—at the same time, of course, they released a link to sign up for the waitlist (“If that don’t fetch them, I don’t know Arkansaw”—Huckleberry Finn, chapter 22).

A perceptive early reader of this essay asked me why Bing was including a whisk as part of Sailor Moon’s salad-making imagery. I don’t know the answer to that one.

Here is FlakPhoto Digest’s excellent overview of the incident, and some musings on what it might mean for photography as a discipline.

Marvelous essay, William. I'm blessed by your thorough research. You have sparked a handful of half-baked offshoot thoughts which I may get around to sub-stacking myself. Trial run here! E.g.,

The Fall (Genesis 3:6) is bound-up in fleshly seeing. (Essentially: looks good to me!) Whether one takes a broad or a narrow view of the second commandment (Deuteronomy 5:8-10, Exodus 20:4-6) the principle is the same as that reflected in Hebrews 11, which begins, "Now faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things NOT SEEN."

The second commandment also hints at the power of images to persist through generations and to steer an entire people group off course. (The golden calf at Exodus 32, and the bronze serpent on the pole at Numbers 21:9, which goes bad by 2nd Kings 18:4 are prime examples of this phenomenon.) I.e., part of the warning for disobedience, and the promise for obedience is bound up in collectiveness--how it emerges from and "speaks" to a group of people, a society, lots of people... a hive.

AI would have no "oomph" if it had no human input to work with. That sounds rather obvious, but the big claims sound similar to the alleged computer proofs of self-generating life. All those fall apart if analyzed closely because the programmers invariably insert information, or assumptions, or a telos, or all three. They can't help themselves. They can't get out of their own way. They end up making then looking into a sophisticated mirror then using it to deny their own cleverness in making it--that is, of man being originally made in God's image instead of a cockroach writing the program. (Stephen C. Meyer's work on information theory is really helpful here, e.g., his books, "Signature in the Cell," and "Darwin's Doubt".)

So, in like manner, AI is a sophisticated way of appropriating others' creativity toward collectivist ends. (From each according to his ability, into a high-tech black-box mystery blender, and out the other end to each according to his "needs".) One could get snippy about that under the banner of copyright, but that's not the main threat or concern--not by a long shot.

The truly ominous angle seems to me closely related to what folks are wrestling with in regard to UFOs (or whatever they're calling them now), psychedelics, and the occult. A big fad idea in the 1990s, fueled by the web's birth (1994), books like Kevin Kelly's "Out of Control" (1995), Malcolm Gladwell's "Tipping Point" (2002), James Surowiecki's "Wisdom of Crowds" (2004), and a Silicon Valley resilience mindset was that the collective has an intelligence all its own.

We take this for granted now under headings like crowd-sourcing, but the basic idea is a hive mind. And so AI looks to me--as a guy who lived through and studies and writes about the '60s and '70s--like a shiny high-tech version of Ouija boards, i.e., openings (human invitations) for an unaccountable set of spirits to tantalize us with their cleverness in the visual domain... which sounds a whole lot like Genesis 3:6. Who is applying 1st John 4? "Test the spirits..."