The Batman (Matt Reeves, 2022)

A wise prophet once told me that Batman can be anything to anyone; that whatever point you want to make, or whatever character angle you want to explore, you can do it with Batman. Is Batman one of literature’s most complex characters, vying for the title with Elizabeth Bennet? Or is Batman merely used by storytellers as a mouthpiece for whatever they want to say? The answer to both questions might be “yes”. Let us turn to Batman’s newest film incarnation, and see what Matt Reeves brings out in the character.

Of course, this film exists in the shadow of Chris Nolan’s trilogy. In those films, my generation was given a Batman who had to struggle against the concept of order as an all-encompassing value proposition, and who lost that struggle in some very important ways. In Matt Reeves’ film, the fundamental ethical struggles revolve around the idea of vengeance, and Batman succeeds in positioning himself against the pursuit of vengeance as a legitimate goal.

In this film, we aren’t given any of the origin story that previous movies have spent so much time on. This is good—we are at the point in our culture where we all know who Batman is, and we don’t need to be brought up to speed (Nolan takes nearly an entire film to do so, and it’s a waste). All we are told is that what we are seeing happens two years into the existence of Batman (aka Bruce Wayne’s “Gotham Observation Project”). Nowhere in the film does Wayne call himself “Batman”, instead referring to himself as “Vengeance”. But does Wayne / Batman really stand for vengeance? Or is he working for something else?

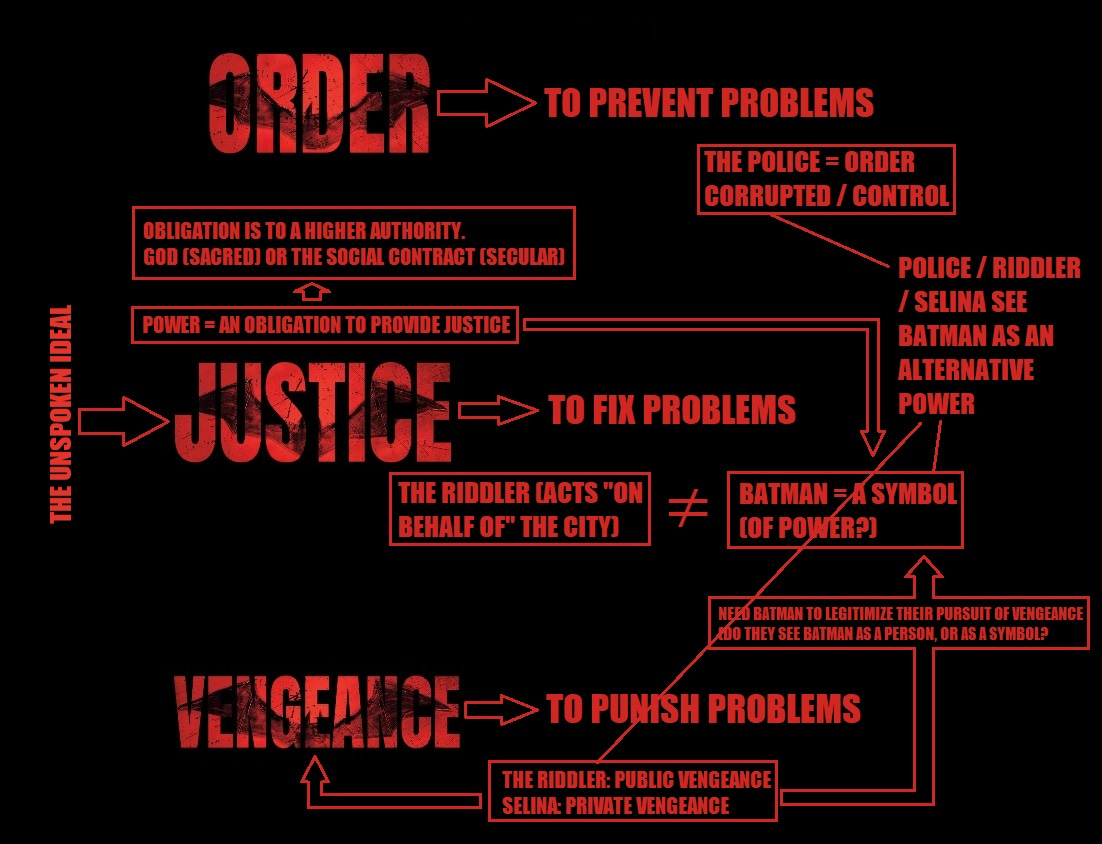

The film’s major characters exist in a rather complicated, symbol-laden relationship with the concepts of order and vengeance. Right in the middle of these concepts is the unspoken ideal: justice.

In The Chris Nolan Batman films, I don’t get the impression that Gotham’s leaders truly desire justice—I see the police as working towards order, and Batman’s antagonists (Ra’s al Ghul, the Joker) as working against that specific conception of order. Bane imposes another kind of order on the city, but since it is not their order, the police cannot allow it to continue. Neither do I see Batman working for true justice; he seems only interested in pursuing the same order as the police, just from a different direction. The police look the other way at Batman’s obviously illegal tactics because his actions advance their agenda.

In this new Batman movie, the police are still interested in order, but it turns out that they are corrupt. What they really want is control—which is even farther away from justice than order is. If Batman is working for justice, he will be working on his own in this film, and the struggle between Batman and the forces of vengeance (the Riddler and Selina Kyle) occupies most of the movie’s emotional and philosophical depth.

The Riddler and Selina Kyle both see Batman as a symbol of something greater than themselves—as power, perhaps, or as legitimacy. This is why the Riddler wants Batman to join him in his crusade to expose all of Gotham’s dirty secrets. With Selina, though, the situation is more complicated. She keeps telling Batman that she can look after herself. So why does she want his help to exact vengeance against her father? She must see him as something more than a fellow masked adventurer.

Bruce Wayne / Batman spends most of the movie trying to define his identity in relationship to the concept of vengeance—in the subway fight scene at the beginning, he calls himself “vengeance”, but I don’t think he really knows what that word means, since he never actually punishes any criminals; near the end, when one of the Riddler’s disciples uses the term to describe himself, Batman’s expression reads as “well now I’ll never use that word to describe myself again.”

This movie shows us a much younger, more inward-looking Batman / Bruce Wayne, one who listens to Nirvana and doesn’t interact with society in the way that we might be used to seeing—Chris Nolan’s Bruce Wayne kept appearing at parties and board meetings, but Reeves’ version goes to one funeral, and that's it. This ties into the story’s major theme—ultimately, the struggle against the desire for vengeance is a solitary one, because vengeance itself is achieved on one’s own. The pursuit of order requires actors on an institutional level, such as the police; but vengeance can be exacted in a variety of ways, ranging from microaggression all the way to the Riddler’s terroristic murders, through individual action.

The problem with vengeance is that it is not the same as justice. True justice admits that not all of the evil in the world will be punished on this side of eternity; that human institutions are not God, and cannot judge cases 100% effectively; and that it is worse for an innocent person to be punished than it is for a guilty person to go free. A civil authority fixated on order and control seeks to prevent problems before they happen, and in doing so, sometimes gets in the way of legitimate actions by law-abiding citizens. To pursue vengeance is not to prevent problems; the goal, instead, is to punish the perpetrators of any and all crimes, often to a degree entirely incommensurate with the crimes’ severity. (Is it really appropriate to have someone’s face chewed off by rats? Or to destroy Gotham’s downtown in the process of picking off the privileged rich, no matter how much you might hate them?)

The police and civil servants in The Batman suffer from the same myopia that the Riddler experiences—they cannot see their pursuit of justice from an eternal perspective, which is why they instead pursue order and control. Now that we have two perspectives, that of the Nolan films, and that of The Batman, it is time to ask: will Batman ever be called to pursue justice, pure and simple? Or will he eternally be pulled in either direction, away from the straight and narrow path?

This Batman movie is darkly beautiful—perhaps the most aesthetically pleasing of them all. The film is filled with visually stunning shots and sequences, and since the emphasis is not on Batman’s fancy gear, we are able to focus on the beauty of Gotham at night. Much could be said of how Gotham is portrayed in Batman films; contrast the urban aesthetics of Nolan’s wide, sweeping birds-eye vistas versus the graffiti and piled garbage in Joker. Reeves’ The Batman is dark, in a literal sense, but that darkness does not feel oppressive or stifling—it is merely the milieu in which Bruce Wayne and co. exist. This highlights the true reason Gotham is worth saving—not because it is grand and beautiful, but because it is home.

To your question about future iterations of Batman: I'd answer that he'll always be pulled from the straight and narrow path, into an excess of vengeance, order, or control. At his core, he seeks human order with the best of human means (intelligence, strategy, violence, and collaboration).

But his characteristic propensity for questionable aims and means is what I find most intriguing about Batman, compared to other heroic figures in the American mythos. He aims to do his own form of good by his own "good" means, but his stories also reveal the limits of his relativism (he's never shown to be straightforwardly moral).