Dostoevsky the Culturally Active Christian

The genius writer was also a potent social critic

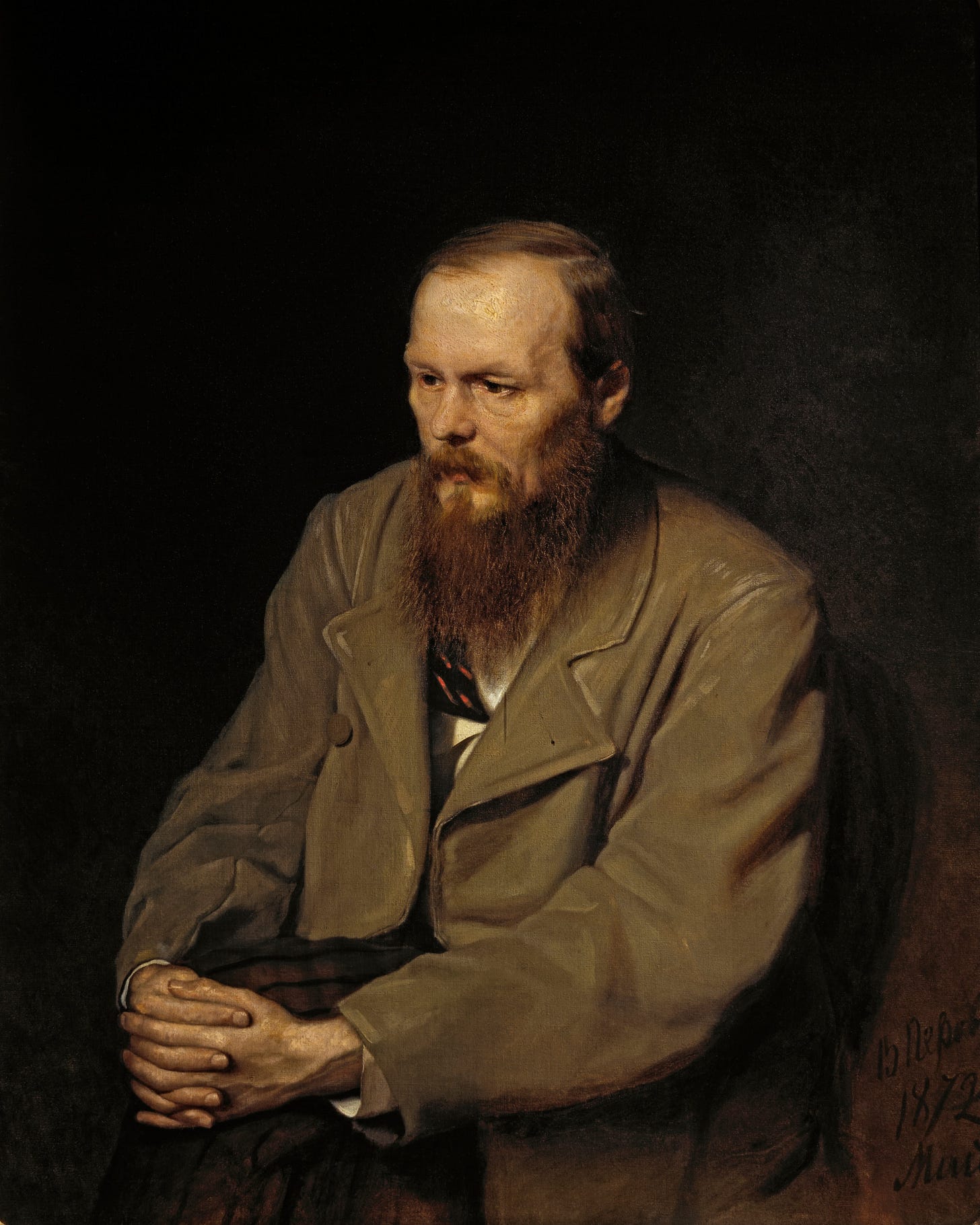

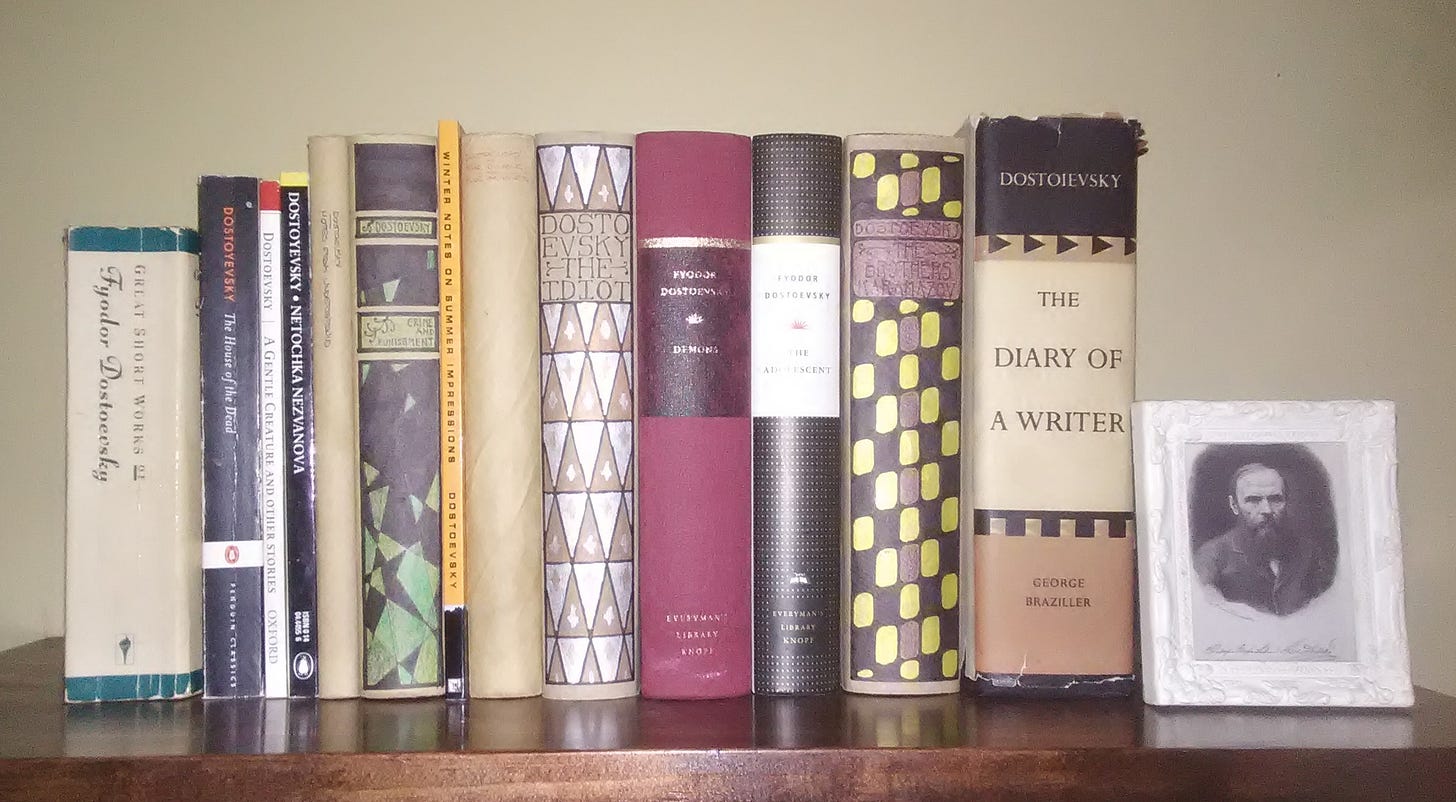

November 11 marked the 200th anniversary of the birth of Fyodor Dostoevsky, universally acknowledged as one of the greatest novelists in all of world literature. His fame rests on the series of novels he wrote in the 1860s and 1870s, among them Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, and especially, The Brothers Karamazov. All of these are profound explorations of the human psyche, and readers have, for generations, been entranced by Dostoevsky’s ability to describe in detail the motivations and feelings of his characters. His stories prefigure the twentieth century’s fixation with psychology, and the existentialist philosophers are greatly in his debt. His works deal with the great questions of faith, doubt, the meaning of existence, and so many other weighty themes that he has sometimes acquired the reputation of a “difficult” writer, one whose handling of lofty and complicated ideas can be intimidating to the novice. But with patience, perseverance, and some introductory material, his works reveal their true value. His novels are consistently regarded by his readers as masterpieces, and Dostoevsky himself as a genius storyteller. Indeed, that he was. But he was so much more.

Dostoevsky is, in a fact, a prime example of an artist using art to affect change in society. At the start of his career, he wrote novels of social realism such as Poor People and Netochka Nezvanova—works which displayed the plight of the lower classes to the unwilling eye of the authorities. He was noticed by the influential critic Vissarion Belinsky, and quickly swept up into the network of socialist-leaning discussion groups that were then talking about Russian societal transformation and change, sometimes of a violent nature. Dostoevsky’s involvement with these groups may not have gone all the way to political upheaval and destruction, but anyhow he was apprehended, convicted, sentenced to death, and at the last minute (right in front of the firing squad!) had his sentence commuted to hard labor in Siberia followed by compulsory military service. During this time, Dostoevsky revisited the Russian Orthodox faith of his upbringing, and found solace in Christianity. From then on, he was an ardent defender of the Christian religion, fighting against what he saw as a tendency among Russian intellectuals to abandon the faith which he saw as a vital necessity to bring about lasting social betterment.

Dostoevsky’s first masterpiece, written upon returning to public life after his exile, was the short work Notes From Underground. In this brilliant little book, half narrative and half theoretical argument, he pushes back against the philosophies of his day, while also writing a very penetrating diagnosis of the mental state of his unnamed protagonist, the “underground man”. More psychologically oriented novels followed: The Eternal Husband, Crime and Punishment, and The Idiot among them. These last two are part of Dostoevsky’s attempt to give expression to his religious belief—in Crime and Punishment, the protagonist finds true forgiveness, restoration, and meaning to his life after coming to faith in Christ; in The Idiot, Dostoevsky attempted to represent what it would be like if another Christ figure, a “positively good and beautiful man,” were to come to earth again.

But Dostoevsky did not only write novels. He was very active in the journalistic debates which formed a large part of Russian intellectual life in the late nineteenth century, founding two periodicals of his own and writing for numerous others. In 1863 he published Winter Notes on Summer Impressions, a sharply critical indictment of the national characteristics and cultural tendencies of the various nations of western Europe. Dostoevsky had no patience for Westernism, the tendency among some Russian intellectuals to copy the ideas of mainstream European culture; instead, he advocated for a return to the ways of the Russian peasantry, and especially their genuinely-held, childlike faith in God.

The main opponents Dostoevsky faced in the 1870s were the radical thinkers which had begun to emerge in the previous decade, the “nihilists” famously caricatured in Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons. Their talk of uprooting all of society, without any real plan for what was to come after, filled him with apprehension; news of a political murder perpetrated by a revolutionary group led by the agitator Sergei Nechaev was the spark that motivated Dostoevsky to write Demons, his sternly prophetic warning against the implications of revolutionary thought. At times fiercely satirical, at times hilarious, and at times deeply depressing, Demons represents Dostoevsky at his finest, fighting a deadly-serious war of words with the intellectual currents swirling around him. Joseph Frank, writing in the introduction to the 2000 Everyman’s Library edition of the novel, calls it “an encyclopedia of the Russian culture of its time” and says that “the more one knows about the Russian culture of the period, the more one marvels at Dostoevsky’s intellectual sophistication, skill and sureness of touch.” Perhaps, for this reason, Demons is also somewhat difficult for 21st-century audiences to appreciate; so much of it is tied to currents in contemporary Russian discourse that it can often be lost on the modern reader. A great deal of the book’s force lies in its satire of Dostoevsky’s enemies, and this satire can easily be missed without knowledge of Dostoevsky’s milieu. The book was very relevant to its time, though, and even though his ideological opponents knew exactly what Dostoevsky was up to, they listened to him and still respected him. He alienated many of the younger generation when he wrote this book, but he knew that the prophetic role of truth-telling is not always easy or popular.

Another of his works, and key to understanding his philosophy and mental outlook, is A Writer’s Diary, the magazine he published in the latter half of the 1870s. The collected run of A Writer’s Diary is more than one thousand pages long; Dostoevsky wrote and edited the entire thing himself. Many large portions of A Writer’s Diary are concerned with political analyses and commentary on what was going on in Russia at the time, but these can sometimes be vital to understanding his vision of what he wanted his homeland to be: a Christ-centered, unified nation, proud of its heritage, and committed to a role as world leader. Sometimes, in its pages, Dostoevsky drifts toward valuing the institutional church, or even the Russian state, more than Christ. Dostoevsky was certainly not as aware of his own biases as he could have been. But he was honestly concerned with the direction he saw his homeland taking, and wanted the best for his fellow Russians; he was not afraid to speak his mind about what he believed to be the serious dangers of Westernism and Nihilism.

Dostoevsky drew heavily from his Christian faith to create his greatest novel, The Brothers Karamazov. Whereas Demons addresses the unfolding developments of Russian thought at a specific moment in time, The Brothers Karamazov has a much more universal relevance, both in time and place, in its discussion of the most fundamental question that anyone can ask: the value of morality and ethics apart from God. The whole novel is built around lengthy explications and disputations of the idea that “if there is no God, then everything is permitted”; the idea is confronted by almost every major character in the book. Lengthy passages of the novel are also given over to descriptions of religious experiences, some good and some bad: Ivan Karamazov even makes a very compelling argument against Christianity in the book’s famous “Rebellion” chapter.

Of course, Dostoevsky himself doesn’t agree with his character Ivan Karamazov. This ability to step away from his characters and let them explain themselves in their own words, without using them as mouthpieces for his own ideas, is one of the hallmarks of Dostoevsky’s genius as a storyteller. He will always be celebrated for his vast, wide-angle perspective on the Russia of his day; every class and stratum of humanity, from princes and titled nobility down to escaped convicts and homeless beggars, is given fair and respectful treatment in his novels. It is sometimes easy to forget that Dostoevsky was writing popular fiction—his plots center around romantic intrigues, murders, and other sensational events, and his characters have (in the original Russian, at least) the sort of pun-heavy or silly-sounding names that readers in English associate with Dickens. Dostoevsky the novelist has earned his place in the hearts of readers the world over. But let us not forget about Dostoevsky the activist, the prophet, the culturally involved Christian who used his art to speak to the culture around him and who tried to show a better way.

> "This ability to step away from his characters and let them explain themselves in their own words, without using them as mouthpieces for his own ideas..."

Love this description! (It's "how I want to be when I grow up.")

A lot of times, in Christian sub-cultures, it's tempting to give a quick answer that doesn't actually engage the person you're talking to. Letting fictional characters "struggle" with moral and ethical problems on their own terms, in their own ways, is a little like the "writers' version" of listening to someone grapple with their problems with God instead of jumping to that quick-and-ready answer of "You just gotta have faith." It takes longer and is more uncomfortable, but does the other option even work anyway?