The Visual Display of Quantitative Information (Edward Tufte, 1983)

Edward Tufte is passionate about the state of the data graphics profession—so much so that he took out a second mortgage on his home to finance the creation of Graphics Press, for the sole purpose of publishing The Visual Display of Quantitative Information, his book of criticism against, and helpful tips for, the discipline of information display. The book was an instant success and has now become the standard work on how charts and graphs can effectively accomplish their intended goals.

Has there ever been a greater mismatch between the blandness of a book’s title and the wealth of enthralling information contained within its covers!? His book is a beautiful object on its own, exhibiting a sparse and precise formality, but the examples he uses to illustrate his theories are eclectic, eye-catching, and lively. Tufte’s prose is direct and forceful because he is deeply concerned with the state of data graphics and is unwilling to equivocate: “It may well be the best statistical graphic ever drawn,” he says of a map of Napoleon’s Russian campaign; he lavishly praises the scatterplot, calling it “the greatest of all graphical designs.” His criticism is just as fierce as his praise is exuberant; he describes one rather ostentatiously ugly graph as “the worst graphic ever to find its way into print.” But Tufte is not praising and ridiculing simply for the sake of expressing his opinion; he is writing because the state of data visualization was, from his vantage point in the early eighties, in serious need of repair. Throughout the book Tufte gives examples of graphs and charts which are deceptive, confusing, or simply poorly designed. What was causing this lack of quality in data graphics?

Tufte blames an entrenched attitude among editors that data is bland coupled with a lack of training in quantitative analysis among professional graphic artists, who consequently see their job as prettifying that which is naturally boring. “Illustrators too often see their work as an exclusively artistic enterprise,” he writes; “those who get ahead are those who beautify data, never mind statistical integrity.” Some of his most impassioned arguments are in favor of giving the data the chance to be richly rewarding to those who take the time to think about it. He praises the data map format, showing how a simple line map of the counties of the United States, color-coded according to some variable, can be fascinating to the viewer in multitudes of ways. Most editors, he suspects, underestimate the interest their data will have on the average reader; as a consequence, the whole discipline of numerical display suffers.

The Visual Display is filled with Tufte’s passionate, careful shepherding of his professional field into a better version of itself. The principles he expounds are well-considered and full of care, and Tufte’s love of the craft shines through. There are a few times, though, where he takes his principles to a place of excess. Sometimes he seems to come across like one of those people on Twitter who approach all of existence in light of their chosen social justice battle. Must every graphic adhere strictly to the principle of maximum data ink? Must all decorations be removed? It’s obvious that Tufte considers graphs and charts to be beautiful, but the kind of beauty he advocates is a stark and spartan minimalism, without any adornment or ostentation.

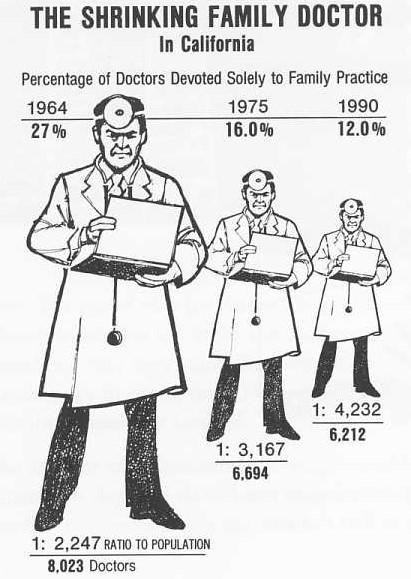

Perhaps the reason for this is that Tufte considers data graphs to be a kind of word and not a kind of image. If graphs are language, the obvious goal would be for them to come as close as possible to an exact correspondence with the facts they represent. Tufte singles out this graph of a shrinking doctor to prove his point that graphical exaggerations are lies. The number of family practice doctors shrunk by 29 percent, but the size of the picture of the doctor shrunk by considerably more than that, for “a lie factor of 2.8.”

But if graphs are images, the point is moot. Anyone who has spent any amount of time thinking about the meaning of images has been confronted with the truth that images are ambiguous, and they often do not clearly correspond with the impressions and ideas they call forth in the viewer. Here is a painting by Alexis Rockman, which is full of all kinds of blatant exaggeration, yet which still makes a valid point about modern factory farming methods:

This sort of thing is encountered all the time in the visual arts. Nobody criticizes Goya’s The Third of May, 1808 or Picasso’s Guernica for being exaggerations or for only telling one side of the story. Precisely because they are such powerful symbols, they tell their side of the story with masterful eloquence. The incredible shrinking doctor does so as well—after viewing that graphic, you are much more likely to believe in a serious problem with access to non-specialized medical care, which is what the makers of the graph wanted you to believe anyway. It is not the fault of the graph makers that they tried whatever means came handily to persuade you of their point of view. The responsibility is yours, viewer of the image, to do your due diligence and fact-checking before you blithely believe whatever pops in your head when you look at a picture. In these days of photoshop, deepfakes, and DALL-E, this is more important than ever.

But what the designers are doing isn’t really deception so much as exaggeration. Tufte quotes a chart specialist for Time who said that “the challenge is to present statistics as a visual idea rather than a tedious parade of numbers.” The attitude among the professional illustrators that Tufte quotes seems to be, “Yes, we are aware that we are adding a layer of interpretation to the raw data shown on the graph, but we are doing that because it’s our job.” According to this attitude, statistical charts are illustrations but they are also embellishments; or as Picasso said, “a lie that makes us realize the truth.”

Tufte admits the fundamental ambiguity of graphs-as-images and the attendant problems which beset the designer: “Misperception and miscommunication are certainly not special to statistical graphics, but what is a poor designer to do? A different graphic for each perceiver in each context? Or designs that correct for the visual transformations of the average perceiver participating in the average psychological experiment? Given the perceptual difficulties, the best we can hope for is some uniformity in graphics and some assurance that perceivers have a fair chance of getting the numbers right.” In other words: faced with the ambiguity of graph-as-image, the task of the designer is to heighten the perception of the graph-as-information. And there are ways to do just that: in the latter part of the book, Tufte gives several ingenious and strikingly effective methods for making the data shine through its visualization, and for coming ever closer to directly communicating the actual data to the viewer of the chart or graph. His principle of maximizing data-ink (the proportion of a graphic which is actual data, as opposed to labels, gridlines, &c.) is easily grasped and is completely sensible, even if he does take it rather far at times.

I’m tempted to say that most of Tufte’s ideas in The Visual Display of Quantitative Information are actual true truth, on the order of statements like “three is greater than two” or “I live in Omaha.” There’s no arguing with some of his concepts—when he says, “Graphics must not quote data out of context,” or “The representation of numbers, as physically measured on the surface of the graphic itself, should be directly proportional to the numerical quantities represented,” my only response is, yes, you’re right. Tufte obviously came to his conclusions after careful, prolonged, deep study of the means and methods of his craft—a study borne of humility and a desire to see his discipline improve and become greater. That is culture care, as practiced by a critic, at its best.

I know nothing of Tufte’s religious beliefs. And really, there is no reason for him to display them. But I would hope that every Christian critic would approach their discipline with the same degree of love, care, and concern that Tufte evidences. It is easy to fall into a kind of religious dilettantism when it comes to Christian engagement with the arts; or, even worse, an attitude that treats the arts as merely a means to a religious end. But Tufte shows that it is possible to work for the excellence of one’s craft purely for the love of it. Too often, I’ve come across Christian art which doesn’t seem to really love the form; it’s an open scandal how bad Christian films can often be, and there are many Christian paintings and poems which seem to be more concerned with conveying a message than with conveying it artistically. Fellow Christians: we can do better. That is the message that Tufte’s work has for me.

Me around the web this week

Review of Betty Spackman’s A Profound Weakness: Christians and Kitsch (Artway)

Review of Alejandro Nava’s Street Scriptures: Between God and Hip-Hop (Ad Fontes)

The Three Ages of Alcohol (Jokes Review)