Empathy at the Bemis: a Gallery Review

I went to see the current exhibit at Omaha’s Bemis Center For Contemporary Arts. The show is called All Together, Amongst Many: Reflections on Empathy, and it runs until September 19, so I saw it at almost my last chance to do so. The show was centered around the idea of empathy, and most of the artworks related in some way to the idea of trying to understand, relate to, and de-otherize people who are either at the margins of American culture, or who are concerned with our culture’s current state.

It’s very hard to review a show like this. Because the program is focused on empathy, I feel almost required to empathize with every opinion or concept expressed in the show. I can’t view a show about empathy in an objective manner now can I? As a Christian, I am told in the Bible to “weep with those who weep”, but I don’t know of any verse which tells me “but first analyze the quality of their weeping”. Should I just evaluate the pieces in the show based on how empathetic I feel after viewing them? That doesn’t seem exactly fair either.

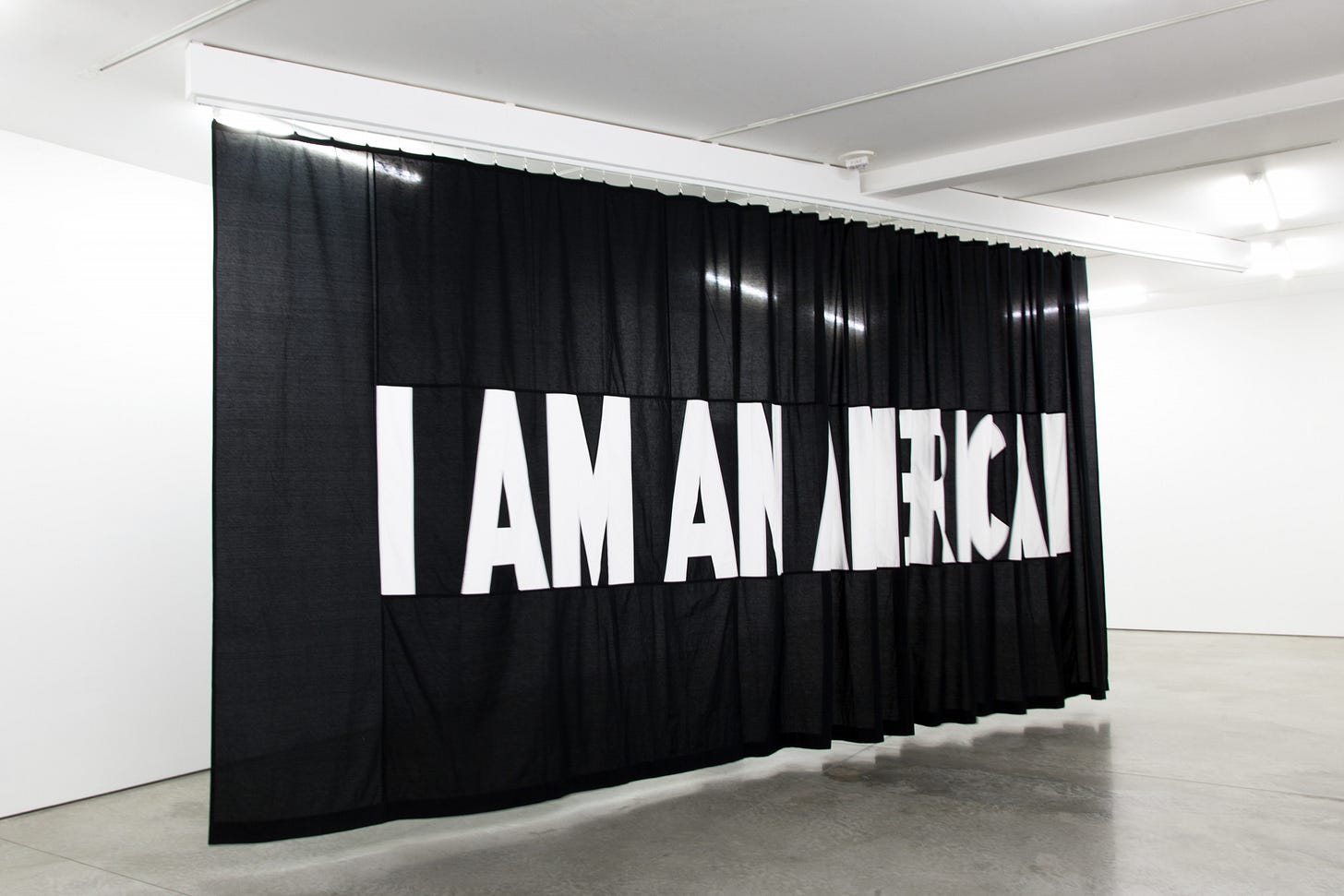

There were two pieces which I thought were especially powerful. The first was by Stephanie Syjuco and titled I AM AN…, and consists of the words “I AM AN AMERICAN” sewn onto a black curtain which is suspended from a track. The first three words are clearly displayed, but the word “AMERICAN” is scrunched up and hard to read . . . As I looked at it, I thought about what it means to be “an American”. Is there any definition of that term that can encompass everyone who lives within the American geographical boundaries? “American” has, in Syjuco’s piece and in regular life, become difficult to interpret. And shouldn’t we empathize with people who feel confused about the definition of “American”, as well as people who don’t seem to fit the historical interpretation of that term?

Another piece was Condition Report, by Glenn Ligon. It takes the form of two panels, one with the words “I AM A MAN” painted on a thickly impastoed white background; the next panel is identical, except for numerous annotations all over the panel, detailing every smudge, wrinkle, crack and imperfection in the panel’s surface. It isn’t common to empathize with men these days—they certainly don’t make it easy. But this piece reminds us that even men, when held under close scrutiny, are full of flaws, problems, weaknesses. And for that, they deserve our empathy—or at least our sympathy.

Other than that, the show left me feeling a little unsure. I used to always read the placards pinned to the wall next to artworks, but I don’t do that anymore; these days I try to understand the artwork on its own—to let it speak to me—before looking at any explanatory material. This was hard to do at the Bemis show, because many of the artworks seemed prohibitively obscure. What am I supposed to make of one of the works, which, the placard told me, was made from soil sourced from indigenous land, and land owned by black farmers in Iowa? Without reading the explanatory notes, I would not have known that. Should the notes be considered part of the artwork? If not, does this situation signify a breakdown in communication on the part of the artist? I’m annoyed at how contemporary artists seem to act as though I need to meet them more than halfway in order to understand their message. But—this is the language that artists are using now, so if I want to listen to what artists have to say, I need to learn a new vocabulary.

Empathy for the oppressed, the marginalized, and the overlooked is a concern that artists have been working with for a long time now. Back in 1850, Gustave Courbet shocked the art world of the time by using the language of heroic and serious paintings in his massive A Burial at Ornans and The Stone Breakers, works which made alive the idea that—oh, how scandalous!—the common peasants were real people too. The show at the Bemis is doing the same thing, with the vocabulary that artists are using today, but . . . perhaps the vocabulary doesn’t have to be so ambiguous?

We need empathy. Why do artists see this, when others don’t? Social media is full of people communicating in a very non-empathetic way, othering people all day long. Perhaps the real value of All Together, Amongst Many is in letting us know the need for empathy, even if its method of discussion is a little hard to understand.

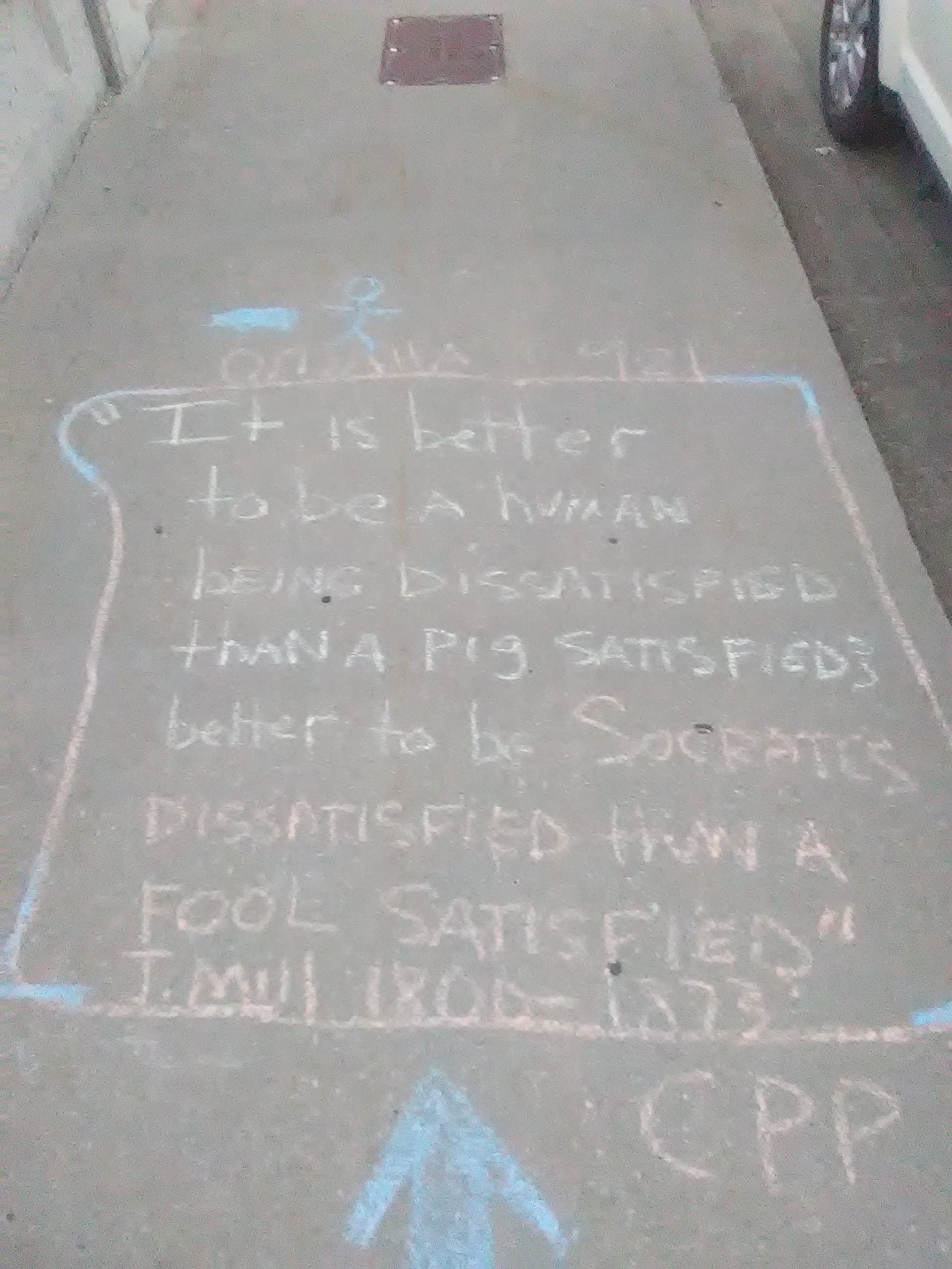

On the way back to my car, I saw this graffito.

I’m not going to comment on it; think of it what you will. Would you rather be Socrates, or the fool?