Thoughts on graphic novels

By now, graphic novels have been firmly ensconced in the pantheon of what counts as writing worth reading. Long gone are the days when Will Eisner’s A Contract with God had a hard time finding a home in bookstores, or when Scott McCloud was ridiculed for saying that he liked comic books and wanted to write them. These days, graphic novels are ubiquitous; some weeks it seems they are the only thing my grade-school-age kids will check out from the library.

Nevertheless, there are some things about the medium of the graphic novel which I find difficult to understand—even after reading McCloud’s Understanding Comics, the definitive work on how graphic novels tell their story. In that book, he writes extensively on nearly every aspect of the craft and mechanics of comics writing, but there are some points which he does not address—points which seem like serious structural problems to me sometimes.

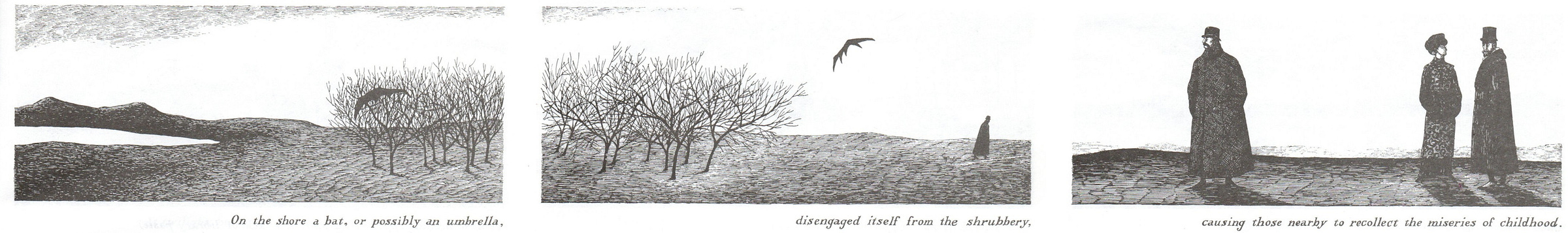

The first thing that I notice when looking at a graphic novel is the enormous amount of space devoted to speech balloons. I find it strange that in a graphic medium, concerned with the layout of the page and the illumination of the story using visual means, so much space is devoted to verbal (non-visual) information. I get the impression that, for comics creators and theorists, the presence of speech bubbles isn’t even a necessary evil; it’s more like a given, like the fact that paintings must have an edge. In Understanding Comics, McCloud goes into great detail about how the words and the pictures on a page can interact and reinforce each other, but he doesn’t explain why they must coexist in the same picture plane. It takes a great deal of dexterity and clever draftsmanship to create a dynamic, coherent image while also dealing with cumbersome speech bubbles all over the place, and there are some comics which don’t do as good a job of this as others. Some graphic works, such as Edward Gorey’s “The Object-Lesson” from Amphigorey, dispense with speech bubbles altogether and convey any necessary words through captions.

An even more obtrusive use of speech balloons is to reveal a character’s inner mental state. Tom Wolfe described (in “My Three Stooges” from Hooking Up) how one of the shortcomings of film, and one of the reasons the novel will never die as an art form, is the ability of prose to explicate the secret thoughts and feelings present in the minds of a story’s characters. Graphic novels sometimes seem to exist in an intermediate position, halfway between prose novels and film. They can show action much better than a prose novel, but not as well as a movie can; they can describe the characters’ thoughts, but in doing so risk the same problems that happen when a film resorts to a voiceover.

Tom Wolfe’s other big criticism of the art of film, that it has difficulty calling attention to the important details in a scene, also applies to the graphic novel. Unless the writer of a graphic novel wants to use up a lot of space doing this—

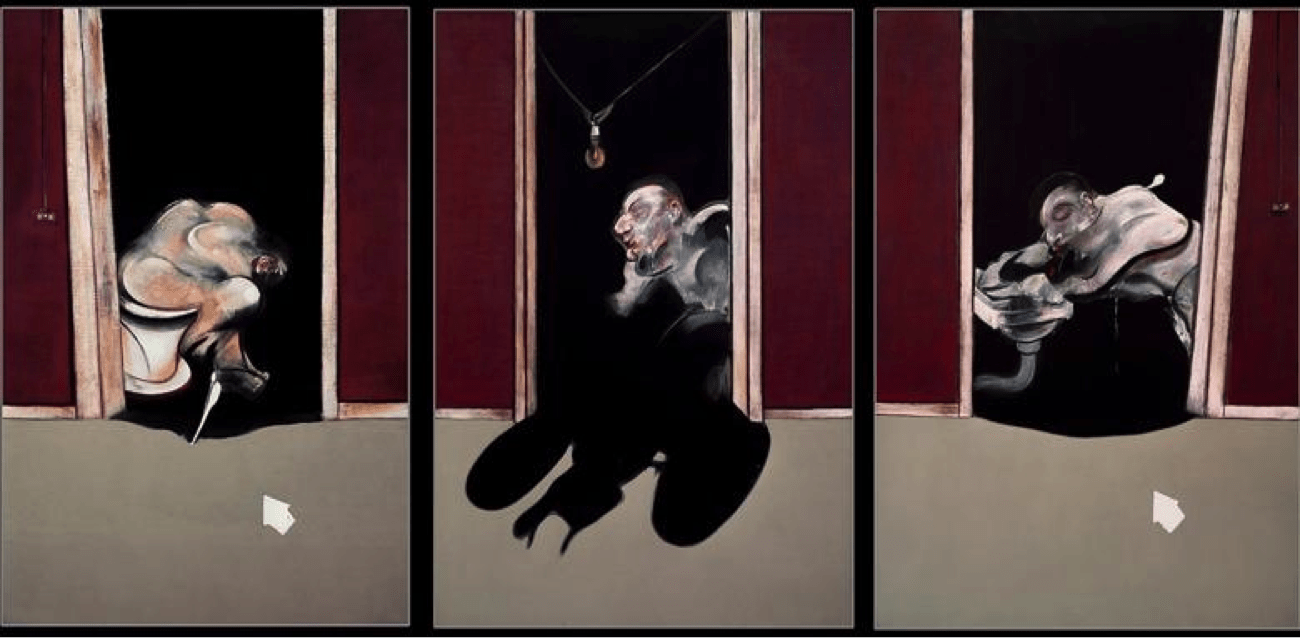

—there really isn’t any way for a visual medium to point out what, exactly, in a scene is important for the reader to notice. I suppose a graphic novelist could employ small arrows in the scene, such as Francis Bacon does in some of his paintings—

—but that approach seems even more obtrusive than speech balloons. Sound is also difficult to convey in a graphic medium. If a comics artist is willing to use onomatopoeic words to describe sounds, there is a risk of cliché (POW! BAM!!); In a graphic novel where realism is an important part of the aesthetic, the sound effects are often just omitted, and the reader is left to detect their presence on their own, such as in this sequence from Watchmen (Alan Moore / Dave Gibbons, 1987).

Sometimes I wonder if all these objections might just point to the possibility that graphic novels may be suited to a different kind of story. I mentioned, earlier, how Edward Gorey uses this kind of storytelling in “The Object-Lesson.” Captions are also how Will Eisner gets most of the story across in A Contract with God, although he uses dialogue as well.

Perhaps the graphic novel achieves its full flourishing when the words and the pictures are allowed to exist more independently of each other. If this is so, then graphic novels have a long history indeed. McCloud demonstrates this in the first part of Understanding Comics, tracing the lineage of the graphic novel all the way back to Egyptian tomb paintings. The Bayeux Tapestry would fall under his definition of “sequential art,” as would such works as Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress. Other works are a little more hard to categorize—Goya’s Disasters of War has no narrative or sequential structure, and if there is one in Max Ernst’s A Week of Kindness, it is very difficult to trace.

Bill Watterson, the creator of Calvin and Hobbes, describes at length the fights he had with newspaper editors regarding his control of how the comic strip would appear in print. His syndicate backed his efforts and required papers to give him a half-page format which he could divide in any way he wanted, allowing for remarkable expressive possibilities. It is interesting that after Watterson got what he wanted, the number of his Sunday strips with scant or absent words and dialogue increased markedly.

This is where graphic novels really come into their own: the telling of a story using pictures in sequential order with dialogue really not necessary at all, and the only interpretive clues being supplied by captions. During the middle third of the twentieth century, artists such as Frans Masereel and Lynd Ward were producing “novels” of great expressive power without any words at all—works which people such as Eisner and McCloud acknowledge to be influential and foundational to their own approaches. Perhaps we will see a resurgence of graphic novels / sequential art which does not rely on words to convey the meaning?

This business of different media being suited to telling different kinds of stories is a fascinating one. The difference is quite obvious when people make movies of books. They are simply not the same.

In the case of movies vs novels, I believe that the base difference is that a movie is addressed to the senses, whereas a novel is addressed to memory. In this sense, the novel is able to bypass the raw input processing of the senses and thus create a more guided experience, balancing immediacy and reflection in ways a movie cannot achieve.

Insofar as graphic novels occupy some kind of half way house between the two, it raises an interesting question of the extent to which they are addressed to the senses vs. addressed to memory. The case of expressing the broken bottle with the visual and relying on the reader to supply the sound is a case of appealing to memory. But the rest of the scene is an appeal to the senses.

Of course, the senses themselves rely on memory in order to make sense of what they see. It is never all sense and no memory. But a novel quiets the senses in a way that allows reflection and experience to operate simultaneously, producing a unique artistic experience. I suspect that a graphic novel does not mute the senses enough to have that effect.

A movie, on the other hand, can bombard the senses in a way that will come close to quieting memory and casting the viewer into an immediacy of noise and light. The graphic novel cannot do that either.

Does this mean that the graphic novel falls between two stools? Or does it mean that it discovers its own fine balance of sense and memory? The former most of the time, in my experience, but maybe the Bill Waterson examples make the case for its ability to do the latter on occasion.

Artist friend drew a lovely ‘wordless’ story some of which can be viewed here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B011BH9O70/ref=dbs_a_def_rwt_hsch_vapi_tkin_p1_i1. The absence of words in this tale really works. It can be a powerful medium. Thanks for the article, William.