Kaneko through the eyes of a child

There is something childish about the works exhibited at the Kaneko Gallery this summer. Maybe I shouldn’t say childish; that word has connotations of immaturity, inexperience, etc. Perhaps childlike is a better word; there is a quality, shared by all the works shown, of exuberant playfulness—a quality found often in artwork made by children. Some of the work on display was actually created by a child, as we will see. But all of it depends not so much on theoretical conceptions or philosophical explanations, but in the surface aspects—line, movement, color, pattern—for its effect. These childlike qualities lead me to believe that the best frame of mind in which to approach this summer’s exhibits at the Kaneko is through that of a child; and if it is difficult to achieve that frame of mind, I simply recommend bringing a child or two with you on your gallery visit—as I did—and ask them lots of questions about what they see. Seeing art through the eyes of a child brings to the immediate fore the truth that all art stands or falls on its own merits. Does the artwork get its point across on its own? Or does it require a critical / theoretical apparatus to do so? With kids providing the commentary, much can be learned about what the art is doing, what effects and emotions it is conveying, and whether or not it is succeeding in conveying them well.

I. BRUCE BEASLEY’S GORGEOUS SACRED OBJECTS

The first artwork encountered at the Kaneko gallery was a massive yet strangely ethereal stainless steel sculpture made of intersecting square tubes twisted into a knot. Situated as it was in a small anteroom, which it almost filled, this sculpture projected a sense of imposing majesty, as if it were a holy relic of some kind. It sat on the level floor but it towered above the viewer, sprawling around the room in frozen motion. The sculpture’s entire surface was exquisitely patterned in identical brushstrokes reminiscent of the scales like a reptile. It suggested all sorts of movement in space and time; the effect I got was of a kind of serene joy—a wildness mixed with peace and silence. It rested gently on the floor as if it were a dancer who had just taken a twirl around the room. But in the next room of the gallery, the twirling and dancing were still underway.

This space is filled with more of the same kind of works, although these are smaller and have a perfectly smooth and even surface. The staging of these sculptures is stunningly perfect. They are distributed around a large, cavernous, dimly-lit room; the same atmosphere of sacredness present in the antechamber is here as well but on a much vaster scale. The effect is of being ushered into a holy place full of sacred mysteries. All around, Beasley’s sculptures curve and cantilever in a high-spirited mockery of gravity.

The lighting casts all sorts of complicated shadows which were almost as interesting as the sculptures themselves. The whole exhibit feels like a reveling in the possibilities of line and gesture, a metaphor for movement. Sculpture like this is more allied with dance than with the plastic arts; and it could be that Beasley is entering into a dialogue with the dance, as if saying “yes, movement is fun and interesting; let’s talk about how much it is so.” Throughout his career Beasley has been making sculptures like this—works which play with notions of movement, sweeping grandeur, and exhilarating flight. Even when he works with old scrap iron, the same weightless qualities are evident. It’s a fun and fascinating dialogue between stolid rigidity of sculpture and the graceful movements of the dance.

II: KANEKO’S COLLECTION

The second exhibit at the gallery is called, simply, Big Clay. It’s an assortment of ceramic sculptures from the personal collection of Jun Kaneko. It’s probably appropriate to mention something about Kaneko at this point: he is a Japanese artist who has lived and worked in Omaha since the early 1990s, and he is most well-known for his large ceramics which often take the form of monumental rounded lozenge shapes (this shape is called “Dango” in Japan). Quite a lot of Kaneko’s work is covered in layers of very colorful glazes set in repetitive patterns. His work is commonly encountered in outdoor spaces, and I like to think of coming across one of his pieces as coming across an interesting pebble on the ground—except the pebble is gargantuan, ten feet tall or more.

As a prominent ceramicist with a long and illustrious career, Kaneko has made many friends in the art world; a number of the works in Big Clay are collaborations between Kaneko and another artist. They all showcase the same sorts of features which Kaneko himself deploys in his own works—most of them are large, even imposing; most of them reveal an interest in surface qualities such as texture, color, and pattern.

My favorite works in this part of the gallery are Viola Frey’s two Fire Suit Men. They are immediately and viscerally understandable; their enormous size and fierce body language give me a feeling of being judged and condemned (by the patriarchy? By late capitalism? Who knows!) They are a little scary, to be honest! When a work of art produces a strong emotion, that’s a definite sign the artist is on to something good.

Thinking about Goro Suzuki’s chairs plunges me into a reverie on the Platonic chair: is it not part of the meaning of “chair” that an object thus named must be able to be sat upon? In what sense, then, are Suzuki’s chairs still chairs? They “look like” chairs, but then so do tree roots, mountains, and even clouds sometimes; are these things also chairs? Suzuki’s chairs exist as chair-like objects in the world; it is really our own minds which class them as chairs—we could easily say they aren’t chairs because they can’t be sat upon, but we don’t.

III: BEYOND THE FINISHING POINT

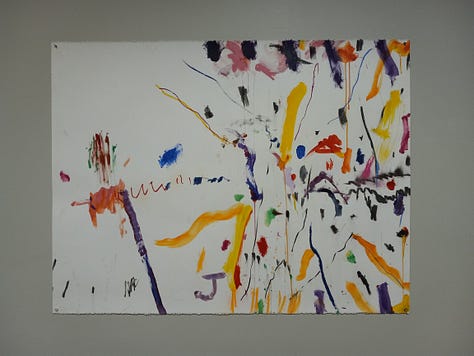

The last room in the Kaneko gallery is hung with large pieces of paper, all the same size, covered in multicolored scribbles. They aren’t preparatory sketches for anything; they aren’t practice for the kinds of color combinations that Kaneko is known to deploy in his sculptures. They are nothing more nor less than the record of an artist having fun! A block of text at the entrance to the room explains:

While teaching at the Cranbrook Academy of Art as Head of the Ceramics department, Jun Kaneko was pondering a crucial determination that all artists must consider: completion. More specifically, he wondered: how does one know when a work or a design is finished? Kaneko relies on his intuition, yet he contemplated what would happen if he relinquished control over when to stop and when to continue.

This query resulted in an unlikely collaboration with the young daughter of a colleague at Cranbrook. The little girl, aged three, was named Ana, and Kaneko gave Ana the power to decide when their jointly created compositions were complete.

Ana came to Jun’s studio every weekend, and together they created drawings. Their collaboration eventually resulted in 82 drawings. He recalls, “I made a rule. When she said ‘new paper,’ no matter what, I had to stop and change the paper. We did that for two-and-a-half years, every Saturday. At one point a drawing might look really good to me, so I would try to trick her into saying ‘new paper,’ but she wouldn’t say it. She kept on working on it, and I started seeing how it was changing. Then it became much better than at the point when I thought we should be finished.”

I’m not claiming that this silly compositional exercise resulted in any spectacular or amazing works of art. Some of them are pleasant and interesting in the way a Kandinsky canvas can be; others are rather haphazard. It was tempting to try and guess which marks were made by Ana and which by Jun; most of the time, though, I had no idea. A few drawings have the artists’ names written on them in big blocky capital letters; in one drawing, Jun only managed to write his J before Ana presumably said “new paper!”

But as a record of an artist doing things in the world, they are faultless. Teddy Roosevelt once said that no one ever had as much fun while President as he had. I can imagine no artist ever had as much fun making art as Jun Kaneko; and that fun spreads out as he promotes the work of other artists. A sense of fun pervades every aspect of his gallery—in the swirling shapes of Bruce Beasley, in the wild and whimsical ceramics of his personal collection, and in the record of good times he spent drawing with a child.

This sense of fun is one of the foundational aspects of all human creativity. Beyond all the theorizing and philosophical justifications for art—beyond the searching for transcendence, for enchantment—beyond all talk of the Good and the True and the Beautiful—beyond all that, there is the human impulse to have fun, to enjoy one’s self, and to have a good time making things.

Do you doubt this is true? Ask a child. They know.

Beasley sculptures quite something - seeing breakdancers!