Miscellany #6: Spring '24

1.

Travis D. Barrett (a fellow Omahan!) writes about his experience binge-watching Neon Genesis Evangelion over Easter weekend, and how the show shares some affinities with the heterodox views of Origen, the second-century church father who believed that souls exist in a disembodied state and commit moral or immoral actions before they are sent down to earth to inhabit physical bodies. His article is presented in a format that can be at times hard to read but it is still a valuable experiment in parallel narrative structures, and the relationships he discovers between the animated series and Origen’s writings are quite intriguing.

2.

Is poetry dying? Depends on who you ask. This essay by James Wilson takes the stance that poetry is, in fact, quite fine, and there is no need to worry; Nik Hoffmann, on the other hand, is concerned for the state of poetry, and especially poetry’s role in passing down “the permanent things” to the next generation. He speaks, here, against the “instagram poets” and the memorializing, in verse, of the trivial and the mundane, instead advocating for a vigorous discussion of the eternal truths of the human condition through the poetic art. The linked article is part one of a three-part series; here are parts two and three.

Related: Here is Victoria’s carefully perceptive review of The Poetry Review—one of England’s most prominent poetry magazines—in which she finds the magazine rather clique-ish and exclusionary. This leads her to speculate on what the ideal poetry magazine ought to be; her thoughts are a very useful stimulus for anyone who wants to make their own zine, blog, or newsletter more accessible and serviceable to a target audience.

3.

Ad Fontes magazine recently published a pair of thought-provoking pro / contra essays on the topic of Christians and AI-generated art. First comes Ian Huyett’s defense of the use of Midjourney to fill in the gaps of Christian visual art (sorry, the article is behind a paywall).

Later, the magazine published this “diatribe” against the use of AI-generated art by Christians; in it, Shuyuan He argues most vehemently against the attitudes which seem to characterize the belief that Ai-generated art is “efficient”: “The attitude of my Christian friends who have embraced AI seems to be, since we Christians have no time for art and no money to commission artists, we should make do with AI. Utility and efficiency! Yes, that is the depths to which we have descended. If Christians, and humanity in general, are not making art, then what are we doing? Earning money? Entertaining ourselves?” Nothing can exist in a vacuum, of course; Shuyuan He wisely states that unless Christians vigorously support the artists in their midst, clients will keep using AI to produce imagery and artworks. Truly, anyone who doesn’t approve of the AI art engines had better be “walking the talk” by paying a human artist to create art.

Whatever your stance on the value or appropriateness of AI imagery, I hope you can agree with me that this kind of impassioned argument on both sides of the issue is a very good thing for the cause of Christians’ involvement in art of all kinds. Too often it seems that my fellow believers are afraid of offending and therefore refrain from engaging in serious debate about these issues. Let’s hope this AI-imagery debate is only the first of many such back-and-forth discussions in the future.

Meanwhile, Yakubian Ape has been chronicling the background and repercussions of the notorious “Willy’s Chocolate Experience” that was inflicted upon Glasgow earlier in the year; this is the third part of his in-depth analysis of every aspect of the incident, in which he includes some very forceful points about what AI art means for the broader culture. His writing style is unsurpassed and breaks all the conventional rules of how to write on the internet.

4.

Here is a quote from Ingmar Bergman (gratitude to Mary McCampbell who first brought it to my attention):

Regardless of my own beliefs and my own doubts, which are unimportant in this connection, it is my opinion that art lost its basic creative drive the moment it was separated from worship. It severed an umbilical cord and now lives its own sterile life, generating and degenerating itself. In former days the artist remained unknown and his work was to the glory of God. He lived and died without being more or less important than other artisans; “eternal values,” “immortality” and “masterpiece” were terms not applicable in his case. The ability to create was a gift. In such a world flourished invulnerable assurance and natural humility.

Today the individual has become the highest form and the greatest bane of artistic creation. The smallest wound or pain of the ego is examined under a microscope as if it were of eternal importance. The artist considers his isolation, his subjectivity, his individualism almost holy. Thus we finally gather in one large pen, where we stand and bleat about our loneliness without listening to each other and without realizing that we are smothering each other to death. The individualists stare into each other's eyes and yet deny the existence of each other. We walk in circles, so limited by our own anxieties that we can no longer distinguish between true and false, between the gangster’s whim and the purest ideal.

Well, what do you think? Is Bergman right to believe that something was lost when artworks ceased to be made as objects of worship? It is undeniable, however, that there have been many incredibly rich and valuable artworks made since the ages when anonymous builders created Chartres Cathedral—does this prove Bergman wrong, or are these artworks merely expressions of some other kind of worship? Perhaps the self-indulgent artworks Bergman criticizes are actually instances of self-worship? In my home state of Nebraska there are two public buildings which are some of the most beautiful and gorgeous displays of craft I have even seen in person—the inside of the state capitol in Lincoln, and Omaha’s Union Station (which now houses the Durham Western Heritage Museum). Are these buildings expressions of worship? If so, what is being worshipped?

5.

Writing of mine published elsewhere:

I wrote about James Elkins’ book Why Are Our Pictures Puzzles? and how it has influenced my own approach to criticism for M. E. Rothwell’s The Books That Made Us newsletter.

My poem “November Evening, ‘23: Observing the Heavens With a Child” was published by Brooke Dreger’s excellent Solid Food Press.

6.

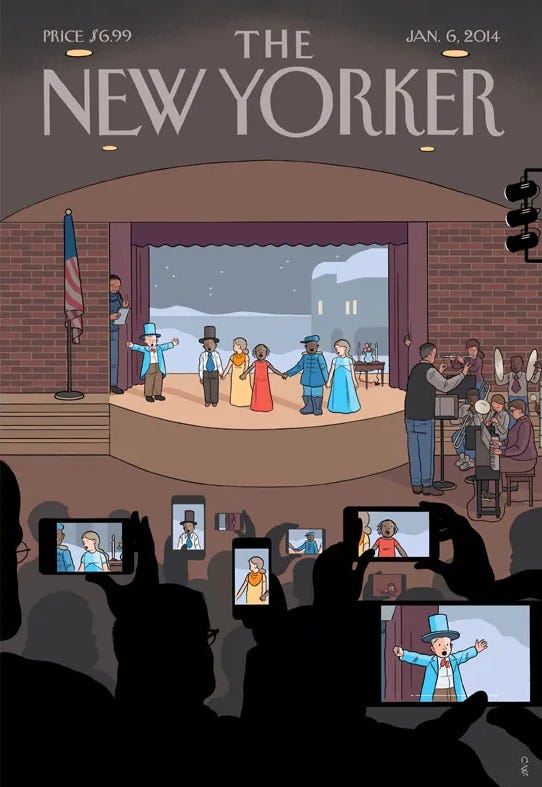

I am enthralled by the work of Chris Ware. Recently I got Monograph, a collection of his art and writings, from the local library and have been struck in particular by Ware’s use of ironic juxtaposition, especially in his covers for The New Yorker. Here are some examples (you can see the images in their entirety if you open them in new tabs; the originals are here, here, here, and here).

7.

Amy Mantravadi takes a sharply critical and highly theologically informed stance vis-a-vis Christa, the sculpture of a crucifix with a female Christ on it in New York’s Cathedral of St. John the Divine. Along the way she wrestles with her own relationship with the institutional church and questions her place in it, but her conclusion is to put her trust in the risen Christ and not the church, whose members are of necessity fallible and prone to error.

8.

Ecstatic magazine has been leading the charge for a rich and vibrant culture of small magazines in the Christians-in-the-arts space and in the Christian culture in general. The magazine’s editors, along with some of the staff from Comment and Plough, recently held a discussion about the role that small magazines can play in the public sphere (this discussion was tied into the Festival of Faith and Writing held at Calvin University in Grand Rapids in early April). On May 3rd, the magazine is hosting “Inkwell: a night of Art and Ideas” in Colorado Springs.

Meanwhile, Conor Sweetman (editor of Ekstasis) writes a passionate appeal for the institutional church, and individual Christians, to provide support for small magazines. “As Christians, it is our responsibility to be aware of how we are satiating our hunger for beauty. Are we developing a taste for what is good and an aversion to the acrid flavor of evil? Are we more influenced by beauty that orients us to the strange and unexpected work of God in the world—or by political slogans and self-help books? The power of the small literary magazine is in its ability to confront us with new ideas, to expand our palates to the overlooked, the strange, the serendipitous, the delightful. This will never be very measurable, but that does not make it unnecessary.” He argues that Christians ought to be ministering to the broader culture through the arts: “Humans will satisfy this hunger for beauty one way or another. As God’s people, we should host the feast.”

Speaking of small literary and arts magazines . . . it is not too late to get your copy of RUINS issue 1. The “grey” variant cover is still available, and if I run out I can easily print some more—if you come around here, I make ‘em all day; I’ll get one done in a second if you wait.

9.

For Interview magazine, Stephen G. Adubato talks with Nicollete Polek about her new novel Bitter Water Opera. The novel is Polek’s attempt to write a story in contrast to “contemporary millennial novels [which] depict a kind of female character that’s consumed by despair, but not consumed by an answer for it.” During the course of the interview, Polek has this to say about religious kitsch in conversion narratives: “When I became a Christian, I was reading a lot of conversion narratives in the Protestant testimonial style and they’re all written horribly. Even as someone willing to accept a certain amount of kitsch, it was hard to read. But there’s a good essay by CS Lewis on Christian literature. At the beginning, he talks about whether one can try to make a Christian cookbook, for example. If you want to make it a truly edifying Christian cookbook, then you would avoid animal suffering, excessive luxury, or human labor that’s extensive or abusive. But ultimately, you can’t really change the way things are cooked. A pagan and a Christian will cook an egg the same way. So I think that’s where style comes in, and where you can prevent kitsch.” In other words, learning the proper forms of the craft is essential to creating an effective work of art which is respectful of the audience and the truths of the world. Polek’s novel sounds interesting; a salute to Kevin LaTorre for bringing it to my attention.

10.

Cormac Jones writes at great length and with incredible detail about the chiastic structures found in the Bible for Jonathan Pageau’s Symbolic World. Jones’ article is a profoundly rich treatise on the symbolic meanings inherent in each part of the traditional fivefold structure of the chiastic form; Jones also shows how many of the Bible’s chiasms themselves contain chiasms in a sort of fractal, “further up and further in” arrangement. I would be very excited to see some of our Christian poets work chiasms into their own poetic creations—any poet who reads this and is inspired to set to work, please get in touch with me and let’s talk!

11.

A good poem. “In Movies” by E R Skulmoski :

I imagined our lives half lived

in rain,

passionate embracing

the ground springing up

lives unquestioned

thrust into our brains.

We would run against the wind

sniffing lilacs,

across fields of long tall grass,

and I would stare

into your pools of irises

searching for stard

while Bach’s Cello Suite no. 1

in G Major plays in the background.

But real life is lived

on the hardwood floors

of our home

where we shout

at the top of our lungs

for our children to go to bed

—our daily liturgy

where I worry about money

and our future

yet he gives his beloved sleep,

as we lay down side by side

and breathe in sync.