Last week, I published an interview with

, author of The Artist’s Mind: The Creative Lives and Mental Health of Famous Artists. This week I’d like to explore the book further; this post is partly a review and partly a rumination on some themes the book brings forward—themes of how the careers of artists overlap with their personal lives, how society as a whole talks about artists, and how artists explain their own experiences.Vercillo doesn’t take a specifically Christian angle in her book; however, many of her themes are directly applicable to Christians who are seeking to engage more meaningfully with the art world and with artists. For example: Christians are told in the Bible to think the best of other people, to act with humility toward them, to love them—basically, to act charitably toward them; the Golden Rule, “do unto others” . . . that sort of thing. But it can be easy to stereotype artists as “crazy geniuses,” or to consider their sometimes-bizarre behavior as obnoxious posturing. But these attitudes aren’t charitable. In The Artist’s Mind, emphasis is given on how the struggles some artists have with mental illness are often comparable to the way the rest of the non-artist population also deals with those issues. Artists aren’t different from other people in this regard; “artist” is not a separate category of human experience. This is how Vercillo phrases it: “Each of us lies somewhere on the mental health spectrum and on the artistic spectrum.”1 But “art” is a means of expression quite different from spoken and written communication. As such, art can be a very useful way to talk about aspects of the human experience—such as mental illness—which can otherwise be hard to discuss. Perhaps this is why artists are sometimes stereotyped as “crazy”—could it be that they are just more adept at discussing these issues, and so they come up in art more often than in the rest of the cultural discourse? Perhaps we should all get out our paints and pencils then. It might make mental health easier for the entire society to talk about.

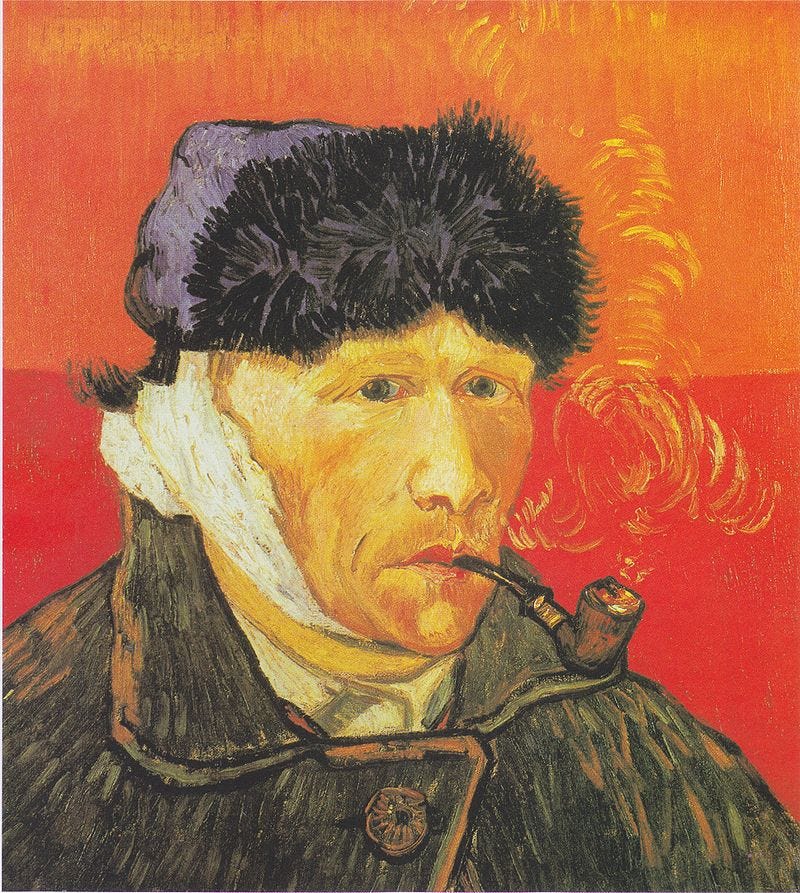

The history of art abounds with stories of the “mad genius”—artists who work obsessively at some masterpiece with a drive and fixation which is nearly incomprehensible to those around them; sometimes they even work at such a furious pace that their own health suffers as a result. Again, we have an example of the broader culture keeping artists at arm’s length—why is the genius “mad” when such a degree of focus and energy is expended on the artistic craft? Why this equation of dedication with mental disorder? It almost feels as though the culture is being dismissive of the artistic pursuits; “You care about that stuff that much? You must be insane.” But there are also many stories of the artist driven to actual mental illness in pursuit of their craft—perhaps the most well-known being the tragedy of Vincent van Gogh. Vercillo talks about him in the book’s first chapter, holding him up as a sort of case study in how issues of mental illness and art are discussed in culture.

The truth is that Vincent van Gogh’s story, while appealingly dramatic, is not in any way typical of the life of an artist—even an artist who struggles with mental illness. Unfortunately, our culture often prefers a quick and ready explanation over nuance and careful consideration. Van Gogh can’t stand in for all artists any more than Dustin Hoffman’s portrayal of Raymond Babbitt in Rain Man is representative of autism spectrum disorder—yet it became, for a time at least, the culture’s default idea of what autism was supposed to look like. Films like Lust for Life2 are well-meaning, but the danger is that theirs will become the default viewpoint for the entire issue. The antidote for this kind of thinking is twofold. We ought to be cognizant of the facts surrounding each artist, and we ought to acquaint ourselves with the whole panoply of artists with similar struggles.

Vercillo’s book does exactly those things. She profiles a very wide range of artists and treats them as individuals, refusing to try to impose an interpretive framework or ideology on them.3 Consider, for example, the careers of Yayoi Kusama and Agnes Martin. Kusama is very open and forthright about her struggles with hallucinations and the effects of childhood trauma; she says that her art is a deliberate means of coping with these issues. In contrast, Agnes Martin never revealed her lifelong struggle with schizophrenia; even though she was institutionalized several times, she managed to keep her diagnosis a secret from the public for her entire life. Their responses, both artistic and otherwise, to their mental illnesses are individualized and personal. Neither of these women can be thought of as presenting the “correct” or “best practice” way of handling these issues. This is how it ought to be.

The overall impression I get from this book is that the mental health history of various artists is a very personal and private matter; it cannot be used to prop up some theory of art, madness, or creativity—and we should not use it as a shortcut to careful understanding of each artist’s unique vision and creative output. “There is a fine line between genius and madness” is, ultimately, not a helpful way to approach the issue. As in all things, the Christian attitude should be one of concern for the truth of the matter and respect for the individual person—The Artist’s Mind is an excellent resource for anyone applying these principles to the study of how artists understand and explain their own experiences of mental disorder.

The Artist’s Mind, 9.

Vincente Minelli’s 1956 film about Van Gogh; although limited, it is still an excellent movie, and well worth watching.

Other than grouping them into broad categories based on diagnoses, which are even then used rather loosely as certain artists are discussed under more than one category.

I recall reading Irving Stone's "Lust for Life" when I was a teen and being impressed. There's something about madness which is particularly fascinating to those coming of age, I think.

Thanks so much for this thoughtful review. I really love your slant on it and I am going to muse a bit more on some of these points. <3 <3 <3