Personal reflections on the end of National Geographic

Some sad news came my way this week—sad for me, and for many other people: National Geographic has laid off all of its staff writers, will use freelance writers exclusively from now on, and will cease newsstand sales of its publications in 2024. I probably should have expected this development since the magazine seems to have been on a downward slide for a while. Formerly the National Geographic Society was one of the primary drivers of exploration, research, and circulation of non-specialist knowledge of the world and everything in it; since 2019 it has been a property of the Walt Disney corporation. I suppose they will keep an editorial staff for the present at least, but what will happen next? Will they eventually use AI to write the magazine’s stories? What will be the fate of the magazine? Whatever it is, it seems to me that this premier institution devoted to “the increase and diffusion of geographic knowledge,” as their motto once stated, is effectively over. This news has very little to do with art, but it does have a lot to do with ruins, as we shall see. It is a very personal thing for me; I have been a fan of National Geographic since I was five years old. Let me tell you about it.

The earliest memory I have of reading National Geographic was when I got a box of old issues from my aunt; this would have been probably 1989 or 1990, and the issues were from a few years prior. She would continue to give me the magazines as she was done with them. I loved them. Since this was the nineties, there was still an extensive culture of junk shops, thrift stores, and other places to buy old things—no one had yet thought of doing all that sort of business on the internet—so I was quickly able to accumulate quite a hoard of issues stretching back to the early seventies. Every once in a while, though, I would find even older issues, sometimes from all the way back into the thirties or even earlier. By my mid-teens I had a very impressive collection going all the way back to 1920, sourced almost entirely from secondhand stores and garage sales.

National Geographic constituted probably half of my reading material at the time. I was the only person I knew who avidly collected the magazine’s back issues, so the hobby became part of my identity. I distinctly remember being twelve or thirteen and planning on going to a big annual junk sale where I’d found old National Geographics before, and praying that God would prevent other people from buying them if there were any good ones; then, thinking better of my self-centered attitude, I prayed that he would help me accept his will if I didn’t find any. So I suppose it could be said that collecting National Geographic brought me closer to God.

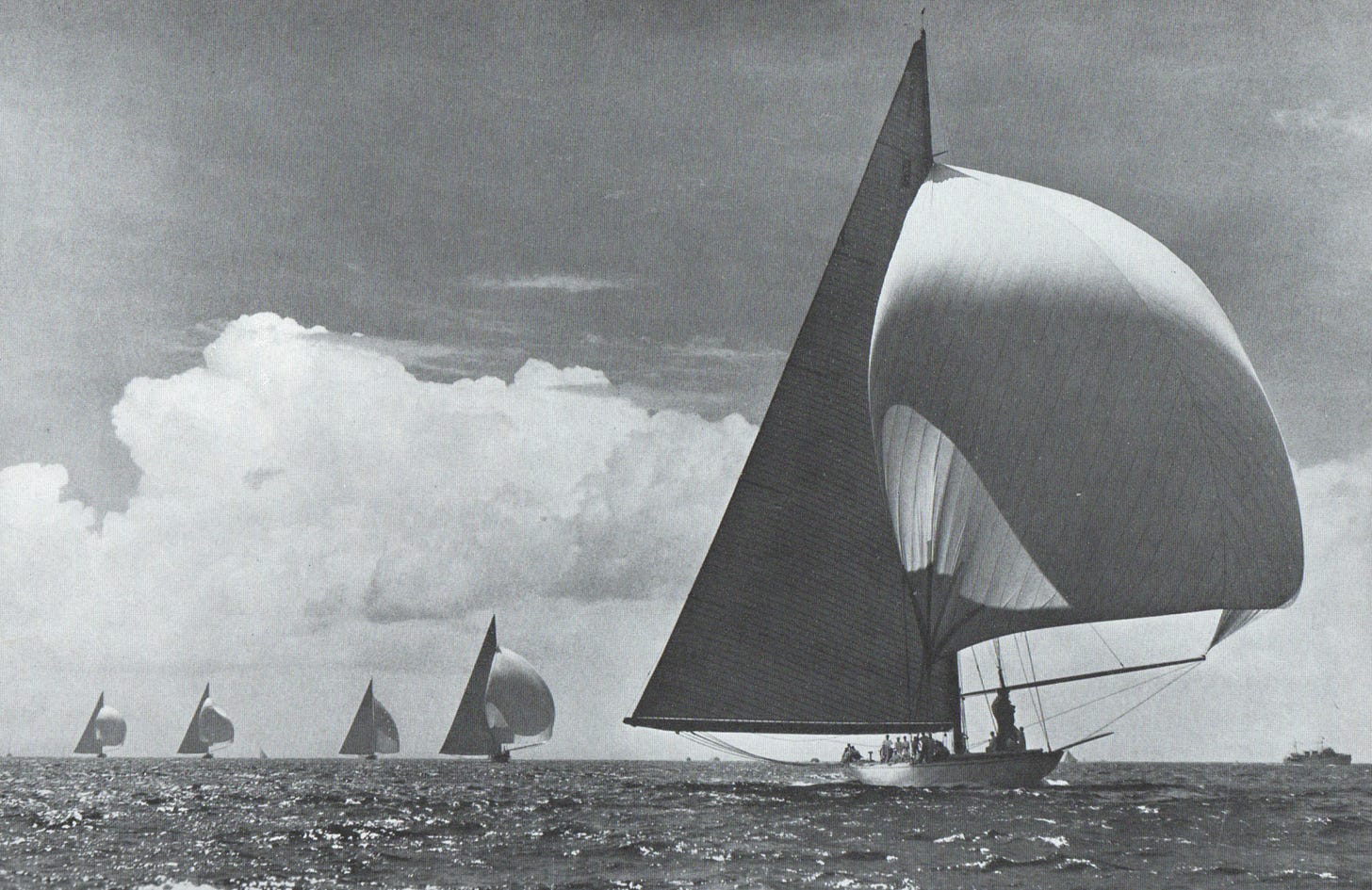

After I got my first job at a grocery store when I was sixteen, I spent nearly all my money three ways: painting supplies, CDs, and old copies of National Geographic found on eBay. After I got married and started a family my collecting habit was set to the side, but I’m quite happy with my modest hoard, featuring original issues back to 1906 and reprints even older than that. I kept away from issues newer than the nineties because I didn’t find them aesthetically pleasant; that little sprig of laurel leaf at the top of the cover conveyed a certain dignity and respect for tradition which is lacking in the post-2000 cover redesign. I gave most of my collection to my younger brother to free up bookshelf space, keeping only the pre-1930 issues, which had always been my favorites. There was so much in each one of them—the November 1927 issue, for example, is 208 pages long and more than three-eighths of an inch thick—and the articles were especially dense with information. Much longer than a short story, they couldn’t be read in one sitting; they were perfect for winter nights, not too logically convoluted to take to bed, and always full of fascinating illustrations. I loved how the issues from the teens and twenties would list the number of maps and illustrations in each article—these were illustrations in the medieval sense of the word: they brought luster, illumination, and enlightenment to the article’s text, and were always spellbindingly interesting, and often very beautiful.

National Geographic was always, for me, a primarily pictorial magazine. I was interested in the articles, but I was completely contented to flip through the pages and look at the pictures, reading the captions but otherwise letting the images narrate themselves. Some of the pictures I encountered were inexplicable, bizarre, and even frightening; I still remember turning a page in the February 1988 issue and being startled by a photo of a man taking off his false nose. The charts, graphs, and maps were always a special treat. My lifelong love of maps, and indeed of all kinds of images, can be directly attributed to the countless hours I spent, as a kid, poring over National Geographic.

But as I got older, I developed an intense fascination with the advertisements. National Geographic had always been one of the major disseminators of middlebrow culture in the twentieth century; as such, their ad pages (tucked unobtrusively at the front and back of each issue, never mingled into the text) featured an array of products and services catering to the fashions, tastes, whims, and aspirations—and insecurities—of the American suburban bourgeoisie. Every imaginable fad and fancy of the middle class can be found hawked in the magazine’s pages, from bonds to refrigerators to cruises to private boys’ schools to word processors. The December issues were replete with ads for gifts like Whitman’s chocolates, encyclopedias, and stationery sets; the April and May issues contained abundant full-page descriptions of the wonders and pleasures of national parks, ski resorts, and beaches in sunny California, just in time for vacation planning season. The history of the American public’s relationship with the automobile was well chronicled via advertisements in National Geographic; it is insightful and amazing to get a glimpse, from our modern vantage point, of a world where tires didn’t yet have treads on them:

Just as the advertisements in National Geographic provide a commentary on the magazine’s readers themselves, the articles, pictures, and maps give an insight into their perspective on the rest of the world. There is nothing else which portrays in more comprehensive detail the optimistic hubris of the post-WWII suburban American mindset. But the roots of this perspective stretch far back into the magazine’s history. National Geographic was notorious for portraying “exotic” cultures in a “truthful” manner, but of course we all know the magazine’s writers and editors modified, distorted, and refashioned the source material to tell the story they wanted it to tell—a pretty girl in a vivid outfit standing next to a bleak mountain scene so the color photography process could be exploited to its full potential; peasants made to wear their wedding clothes so the Americans could see them in their “authentic native dress.” I’m aware of only one occasion when the magazine acknowledged the reality of their own foibles, in the absolutely splendid September 1988 centennial issue. But significant distortion of perspective had been wrought on generations of readers; it was well into adulthood before I was able to update my mental image of cities such as Beirut and Lhasa to include superhighways and high-rise apartments. Despite these shortcomings, however, reading National Geographic helped me situate my own culture within the broader world; my limited perspective was widened by reading, in the magazine’s pages, of places and people which were very different from me. Some authors have detected, in the magazine’s tone, an air of condescension to those cultures, but I never did. Instead, what I saw was that the whole world, in all its multitudinous array, was interesting and worth learning about.

And what a variety that was, as portrayed inside the magazine’s yellow-bordered cover! I first learned about how dinosaurs were warm-blooded from the August 1978 issue. I stared for hours at the extremely detailed inventories (with superb watercolor illustrations) of fishes, plants, insects, and mushrooms which were a feature of the magazine throughout the twenties and thirties. The first time I thought about how cities function was after reading the May 1960 article about Brasília. The juxtapositions the magazine incorporated into itself were almost as jarring as the “now . . . this” of TV news, but at least the magazine could be put down between articles. National Geographic was worried about the environment and at the same time it was enthralled with archaeology; it thought about geopolitics and the planet Neptune in almost the same instant; an article about the Shakers was presented at the same time as an article about aphids (September 1989). The distant past was constantly bumping into the contemporary present, as well as the timeless world of nature: the May 1918 issue featured, as its sole content, a large foldout map of the Western Theater of World War I—in minute detail, with every village and road crossing marked—and an equally detailed description (“With 32 pages in full colors”) of “The Smaller North American Mammals.” This eclecticism and breadth of scope continued throughout the magazine’s history; such a combination of technical analysis, up-to-the-moment reportage, and sheer reveling in the beauty and variety of the world was the hallmark of the magazine from its earliest beginnings to the present day. The September 1996 issue has, for its table of contents on the cover, this eclectic mix: “Scotland—Gaza—Scythians—Tarantulas—Fire.” Is there anything that could be ruled out as not likely to appear in the magazine’s pages?

There was always the awareness for me that they were still publishing, still making new issues, and so collecting National Geographic was necessarily a game of catch-up. Now, National Geographic, the institution, is gone, gone like so much else of what we now call legacy media, another casualty of the internet’s information superhighway / creator economy / social media-as-journalism ethos. Is the democratization, the Wikipediazation, the juggernaut of instantly available content on the internet a net gain, or does it in fact represent a loss for human culture and discourse? I don’t know—I really can’t be sure, and the fact that I’m unsure is disturbing in its own right. Meanwhile, National Geographic is now just a brand, a particular kind of travel content for Disney, another place for globetrotting influencers to pitch their Twitter threads. Reading and collecting National Geographic is now an exclusively past-oriented occupation, like reading and collecting The Century or Scribner’s, The Saturday Evening Post or Life. The magazine is not part of a living tradition anymore. Its ruins have now passed into the hands of collectors and curators such as myself.

Aren’t we all curators, choosing which books to read, what music to hear, what ideas to think about? Of course we are—curating and collecting are ways to stave off the inevitable forgetfulness of history, the dark void that threatens to swallow every single particle of human invention, action, and thought. But collecting is also a deliberate stance in favor of the aesthetically pleasant, a conscious vote for beauty, curiosity, and fascination. My favorite items to collect are ones which have an air of mystery or inscrutability about them—which is why I collect security envelopes (who designs those things, anyway?) and abandoned grocery receipts (were they making a specific dinner? Did it turn out well? Or were they doing the regular shopping?). And since all collected items are by definition part of the past (you can plan on collecting something in the future, but you can’t actually collect it until it has been made), curating a collection is a way to resist the myopia of the present moment and demonstrate humility and respect for the ways of people who inhabit a different time and place from ourselves. Collecting is a love for the past, manifested in the present.

Like all lovers of old things have done throughout the ages, we collectors will pick through the ruins of National Geographic, examining the pictures, puzzling over the maps, and reading with wonder about a strange and distant world. Our collecting will be tinged with a wistful nostalgia, mixed with despair—despair because I don’t think we will ever again see, in one publication, the scope, breadth, depth, and beauty—the deliberate editorial stance of curated curiosity—that the writers of National Geographic gave us.

Since the 1960s, a NatGeo subscription renewal had been a traditional (easy) Christmas gift in our family. But ~20 years ago it began to become clear that it was becoming a visually attractive shill for every globalist agenda out there. I still accepted the gift... but I read it with increasing skepticism... and no longer gave it to others. Somewhere in there I stopped being able to read it in the same way that I can no longer read the NYT or Boston Globe or WaPo without my teeth setting on edge.