North Star (Philip Glass, 1977)

(Note: near the end of this essay there is a passage which mentions nearly two hours’ worth of music. Instead of giving lots of links to different tracks, I collected all the music into this Spotify playlist. I did leave one link, to a nifty animation / music video thing.)

Will Philip Glass be regarded by future generations with the same degree of adulation that we currently afford to Beethoven? Both composers were innovative, pioneering a way of thinking about music that was barely imagined before them. Beethoven is the symbol of music with a linear structure, advancing through developments and expositions to a formally complex and logically involved conclusion; Philip Glass is the opposite of all that, the high priest of music that lives in the moment, barely changes at all, and revels in what non-fans might consider pointless repetition. I’m a big admirer of Philip Glass’ music, but I have a hard time getting people to enjoy and appreciate it with me. The problem is, Glass’ early works are so . . . LONG. His Music in Fifths goes on for twenty-five minutes; Music in Contrary Motion is about the same length; and his Magnum Opus, Music in Twelve Parts, can run to nearly four hours. That’s a huge time commitment! I’m not able to listen to Music in Twelve Parts more than once every couple of years, and when I do, I have to be doing something like painting a room, or I’ll develop bedsores.

Of course, this is part of their power—Music in Twelve Parts wouldn’t be nearly as earth-shattering if it weren’t as long as it is. But you have to admit, being so long makes Glass’ music difficult to comprehend, and deters a segment of the potential audience. This is a common problem is many other arts, as well—how many people are out there who won’t read Proust’s In Search of Lost Time? Who actually gets to look at Monet’s water lily paintings the way he intended?

So it is with amazed gratification that I am totally digging Glass’ 1977 album North Star. The album is a very minor element in Glass’ works; it is apparently the score to a film about the sculptor Mark di Suvero, but it is not listed on Glass’ Wikipedia page. The album is made up of his signature looping, swirling forms and additive rhythms, but condensed to the lengths of pop hits. The longest track on the record is only 4:45; the average length is 3:30. In other respects, though, the record is a representative assessment of Glass’ concerns at the time, scored for voices and keyboards, and featuring his trademark overlapping rhythmic figures. Because the songs are so short, Glass is able to create his grand, sweeping gestures, his harmonies that revolve into position with profound and intense clarity, without requiring the listener to exhibit the patience of a saint. The songs sometimes even begin to sound like verse-chorus pop songs (“Victor’s Lament”). And Glass can do interesting things with his proto-melodies and voice / organ combinations, like he does on his longer pieces, without wearying the listener’s ear (“River Run”). “Are Years What?” sounds like it could be the Music in Twelve Parts single edit.

Philip Glass’ music, in the idiom of pop singles, is something that I never knew existed, and something I want to hear more of. I want to hear whole albums of this kind of quick-snack-instead-of-full-meal minimalism. But I don’t think I ever will—and this leads me to an interesting point.

During the sixties and seventies, Philip Glass, Steve Reich, and the rest of the pioneers of minimalism in music were working under the general umbrella of “experimental music”—music which was devoted to trying new techniques, new structures, new ways of musical expression. Each particular minimalist composer can be associated with a specific stylistic innovation—Steve Reich with his phased parts, Terry Riley with his tape loops, La Monte Young and his long drones, Glass and his additive rhythms—and they each experimented and developed their innovation for a considerable amount of time (Young, in fact, is still working with drones). But they did not try out each other’s style innovations—Glass didn’t work with Riley-style tape delay systems, for instance.

On the surface, this makes complete sense—if you aren’t being innovative in your own right, what kind of experimental composer are you? Of all the genres, experimental music has the least tolerance for stylistic copying. Contrast this with radio-friendly pop, where stylistic similarity is actually a good thing.

There was a time when pop musicians listened to the doings of the avant-garde and borrowed some of what they heard. Alex Ross, in The Rest is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century, recounts that

Paul McCartney had been checking out Stockhausen’s Gesang der Jünglinge, with its electronic layering of voices, and Kontakte, with its swirling tape-loop patterns. At his request, engineers at Abbey Road Studios inserted similar effects into the song “Tomorrow Never Knows.”

There are hints of Pierre Schaeffer and other Musique Concrète composers all over late-sixties / early-seventies art rock, from Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band to Dark Side of The Moon. But are there any pop songs which borrow the vocabulary of the minimalists? Radiohead’s song “Weird Fishes / Arpeggi” features a very repetitive structure in the accompanying guitars, but if we’re going to count that sort of thing, basically any song with a part that doesn’t change much could be considered “inspired by minimalism”—Taylor Swift’s hit single “Love Story”, with its repetitive vocal line, for instance. The Who famously appropriated the hypnotic keyboard swirls of Terry Riley’s A Rainbow in Curved Air in their songs “Baba O’Riley” and “Won’t Get Fooled Again”. But there really isn’t much else in the way of minimalist-inspired pop or rock music.

Glass’ methods, and his signature sound, are found quite frequently in the ambient genre (Loscil’s “Red Tide” from their Monument Builders album is one example). And some music in the sample-based / EDM genre comes close: tracks from Daft Punk’s first album such as “Fresh” or “High Fidelity”; parts of The Avalanches’ Since I Left You (the transition between “A Different Feeling” and “Electricity”, and the subsequent beat drop, reminds me strongly of the similar transition / beat drop between parts 9 and 10 of Music in Twelve Parts). The critics have picked up on the indebtedness to Glass- and Reich-era minimalist music that is evidenced in Orthrelm’s massive, brain-melting OV album; I dare you to listen to it all the way through.

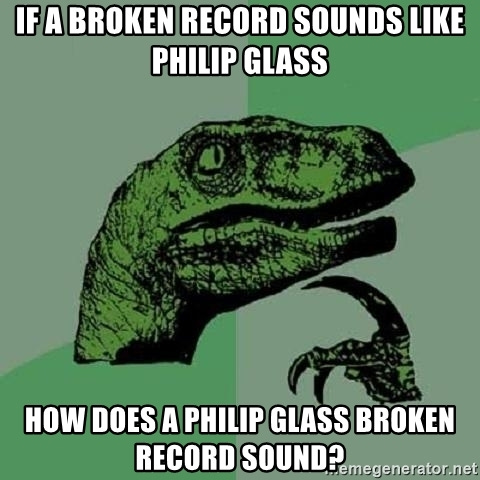

I call for a new cross-pollination between the worlds of contemporary classical music and radio-friendly art pop. Will there be a time when pop music embraces the styles and techniques of minimalist music, in the same way the bands like The Beatles and Pink Floyd experimented with the Musique Concrète techniques of Stockhausen, Boulez, and Pierre Schaeffer? Will Lady Gaga’s next record sound fundamentally the same as Glass’ North Star? Or is minimalist music too poisoned in the popular consciousness, good only for being the butt of jokes like this one:

Some more live music links

Here is a good live rendition of Terry Riley’s A Rainbow in Curved Air, arranged for six-person chamber group.

This performance of Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians is spellbinding; I played it for my grade-school-age kids, and they watched the whole thing.