One Christian's thoughts on the usefulness of art

I am a Christian, and I care deeply about art. Why? Isn’t there something more useful I could be involved in? Isn’t it more important to engage in the political arena? Art is just decoration or entertainment anyway—why would a Christian, who feels compelled to be involved in culture, want to waste their time on art?

I say nonsense to all that. Art is the most powerful way that people can communicate, share ideas, and change the world. Art and culture are intertwined in complicated ways; it could be said that art is culture, and culture is art. Art is a powerful force for achieving cultural change; as Percy Bysshe Shelley said in his “Defence of Poetry”, “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.”

Artists work very hard at what they do, so I think it is a mark of respect to treat all artists seriously, and to engage intellectually with a work of art—not just to passively consume art. It is time for Christians to stop thinking about art as mere decoration or something superfluous added on at the end, or that can be ignored by the people who are focused on “more serious” matters. On the contrary, art is one of the most important and serious pursuits that anyone can undertake with a power and influence that many Christians take entirely for granted.

Art is the “how” of all human activity—and how we do things has enormous implications for the importance, value, and respect that we give to our activities and to other people. Christians would do well to remember that our God is a creative God, concerned with even the minutest artistic details, and when we create art, we are emulating God. When we consume art—listening to music, watching movies or television, going out to eat—we are making a value-judgement on how that emulation should proceed.

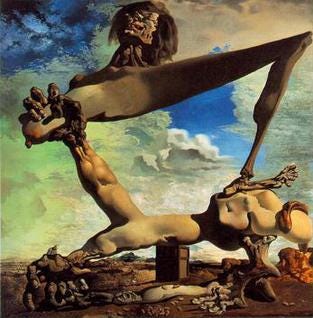

I’ve heard many Christians say that they don’t really get into much of the past century’s art because they perceive it as . . . ugly. They don’t like this sort of thing:

But I think Christians don’t need to be scared by this type of art. Remember that artists are trying to communicate—and frequently, an art of ugliness is an art of despair. Artists are very aware that there is something broken about the world, and their expression of that awareness can sometimes be disturbing or unsettling. But when faced with the problem of existential despair, a conventionally pretty painting would be like lying, or avoiding the elephant in the room.

“But”, say some Christians, “what about all of that abstract art, that isn’t about anything at all? Why make art that’s just shapes and colors? Shouldn’t paintings represent reality?”

But these paintings do represent reality – a reality of emotions. What emotion does this painting express?

It evokes a feeling of calm and serenity, doesn’t it? What about this painting?

It expresses a sense of excitement, perhaps agitation. These emotions are just as real, just as deserving of artistic representation, as the landscapes and human figures found in traditional “representational” art. And the study of how the artists of the twentieth century created a visual language to express emotions, moods, and feelings in their art, without overt reference to the physical world around them, is one of the most fascinating studies in aesthetics.