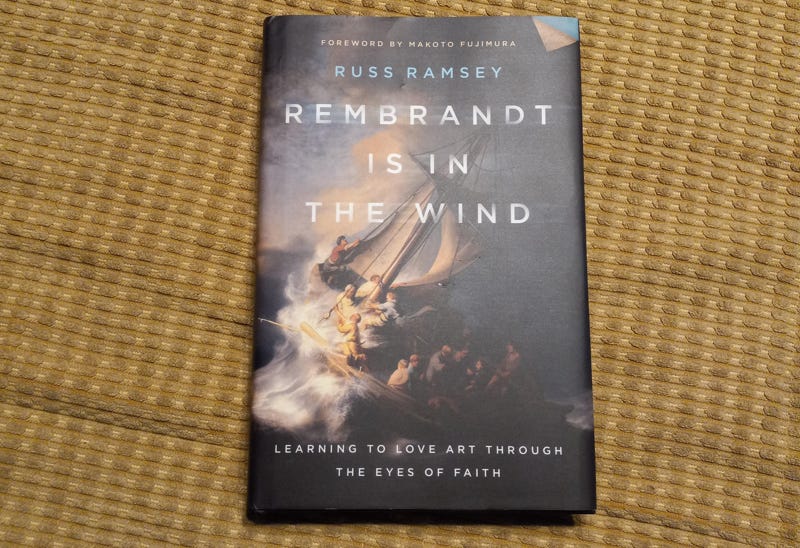

Rembrandt Is in the Wind (Russ Ramsey, 2022)

How are Christians to serve Christ through art? What should be their attitude towards art and artists? How should Christian artists go about their careers? These questions will be new for each person who asks them, and will have different answers for different people (or for the same person at different points in their life.) Russ Ramsey’s recent book Rembrandt Is in the Wind: Learning to Love Art Through the Eyes of Faith is a useful catalyst for thinking about these questions.

Christians have something valuable and important to say to the art world—and the art world has something of value to say to Christians. Surprisingly, I still find Christians who claim that the arts are “superficial” and “frivolous.” This sort of thinking has got to stop; Ramsey’s book explicitly stands against that idea. Art can do so much—from revealing our hidden flaws and weaknesses to giving us a glimpse of eternity.

Although the book is subtitled “learning to love art through the eyes of faith,” Ramsey’s focus is really on the creators of the paintings he discusses, the times they lived in, and how their artistic practice affected the world around them. It is often easy to overlook the artist behind the art; this is sometimes a position that I deliberately take, here at RUINS. But we can’t let ourselves forget that the art which has survived the ages was once an art of the immediate present, with a relationship to that present that we would do well to remember. So Ramsey’s book is a necessary counterpoint to my own “observing the ruins” stance.

Two themes stand out throughout this book: beauty in brokenness, and the importance of community. Ramsey gives us many examples of art of great beauty and power which came from muddled, messed-up lives. Van Gogh painted a portrait of himself after he had cut off his own ear; Ramsey imagines himself in Van Gogh’s place, creating this self-portrait, and asks,

If I’m drawing the self-portrait dishonestly—pretending I’m okay when I actually need help—I’m concealing from others the fact that I am broken. But my wounds need binding. I need asylum. And if I can’t show that honestly, how will anyone ever see Christ in me? Or worse, what sort of Christ will they see?

(The forgetting of this point is something that has always bothered me in explicitly Christian art, especially Christian films. So often, I’ve heard that Christian art must adhere to some ideal of “beauty” or have some redemptive element in it. But there are many films which would never be classed as explicitly Christian, yet which exhibit a serious, sober-minded honesty about the brokenness of humanity and the sinfulness of sin, which I find much more consistent with a Christian awareness.)

Van Gogh has already been mentioned; we also learn about how Caravaggio was on the lam for murdering a fellow artist while creating a new conception of light and chiaroscuro in his groundbreaking religious pictures, and how Edward Hopper’s entire career was conducted in the shadow of a strained, troubled marriage. By now, fortunately, it is becoming out of fashion to romanticize the artist, to think of artists as some special breed, immune to the petty things of life, and “attuned to the highest strumblings of the fundamental aether.” The reality is that the life of an artist is hard, boring sometimes, and closely involved in our human capacity to make a mess of existence. But such brokenness does not ever get in the way of the truth that can shine through the works of great artists.

The second half of the book emphasizes Ramsey’s other big point—the importance of a community of friends, associates, and acquaintances which make up the support network that artists need to be able to create their works. An artist alone, isolated from actual life, hiding in some garret and painting furiously for no one, is a tragic being. People were created to exist in community. Just like the rest of us, artists exist in a densely intertwined web of relationships. And lest you think that he is merely talking about agents and gallery owners, Ramsey lets us see that it’s turtles all the way down:

Consider a painter like Johannes Vermeer. He likely used Antonie van Leeuwenhoek’s lens. But what had to happen before he ever put brush to canvas? Someone had to stretch that piece of canvas across a frame. Both the canvas and the frame had to be made. So did the tacks that fixed the canvas to the frame and the hammer that drove them in. Consider the easel on which the canvas sat and the lumber mill from which its pieces came, with its drying racks, saw blades, aprons, and brooms, all of which were also made. Consider his paintbrushes—with their turned and sanded handles, their hammered-thin ferrules holding the finely trimmed bristles in place—arranged clean and neat upside down in a cup that was also made, and the mortise and pestle he used to grind his pigments and linseed oil into paint.

So many things were designed and fashioned in order for the artist to sit down and do their work—even the chair and the floor on which it rested. And so many people contributed their skills: carpenters, weavers, potters, metalsmiths, brush makers, architects, distillers, and even lens makers. When we stand before a Vermeer, we are seeing not only his work, but also the work of all these others and many more.

The last artist that Ramsey profiles is Lilias Trotter, who gave up a burgeoning artistic career (which included personal lessons from John Ruskin!) to serve as a missionary in Algeria. In a book about artists, why does Ramsey end with a chapter about a person who renounced their art? Perhaps because she really didn’t. Lilias Trotter was still an artist during all those years she spent ministering to the Algerian people, even if she never showed a painting; her art was turned in a different direction, that’s all.

Ramsey’s book ends with an envoi in which he encourages artists who might be considering giving up on their art. “Don’t quit,” he says; “it’s okay to be a slow learner. Just don’t bow out of the work of beautifying the gardens you tend.” This is a subtle allusion to the famous ending of Voltaire’s Candide, in which all the philosophical burdens, second-guessing, and self-doubt that can sometimes plague the artistic life are not as important as our duty to cultivate the garden, or as Princess Anna of Arendelle puts it, to “do the next right thing.”

The “right thing” for an artist is to make art. And even if you are not an artist, you still work at some kind of craft. Whether you take care of children, file paperwork, cook meals, wash windows . . . whatever it may be . . . Ramsey calls you to be consistent in honing your craft—and working toward mastery. Not all art is hung in museums; I have a friend who said he was inspired to be a better husband and father because of a cocktail he had in a bar in Denver once. “The world is short on masters,” Ramsey says. If anything is to be learned from examining the lives of artists, it is not that they are in a plane above; it is that the capacity to be an artist resides in each of us.