Critics have a much more useful role than you might think

There’s no accounting for taste; beauty is in the eye of the beholder; to each their own. It just doesn’t make sense to expect everyone to have the same taste—in movies, in music, in art—in anything, really—and besides, there’s so many different genres and styles to choose from, all made instantly accessible through the internet, that anyone can find exactly what they want, at any time, in any amount. If all this is true, what is the role of the critic? As Jean-Michel Basquiat said, “I don't listen to what art critics say. I don't know anybody who needs a critic to find out what art is.”

Artists of all kinds have a difficult relationship with the critics. To them, critics are seen as some kind of parasite, feeding off the efforts of artists but not actually able to contribute anything of value to the creative endeavor. When artists discuss critics, their feelings range from frustration, annoyance, and exasperation all the way to hostility and contempt:

Criticism really used to hurt me. Most of these critics are usually frustrated artists, and they criticize other people's art because they can't do it themselves. It's a really disgusting job. They must feel horrible inside. —Rosanna Arquette

A true artist is expected to be all that is noble-minded, and this is not altogether a mistake; on the other hand, however, in what a mean way are critics allowed to pounce upon us. —Ludwig van Beethoven

Don't pay any attention to the critics. Don't even ignore them. —Samuel Goldwyn

And of course there is the scene in M. Night Shyamalan’s Lady in the Water, where he lets Harry Farber, the annoying film critic, get killed and eaten by a monster. If that’s not a comment on how artists value the critics, I don’t know what is!

Even the critics themselves can sometimes feel that there really isn’t any purpose or value to their endeavor:

One gets tired of the role critics are supposed to have in this culture. It’s like being the piano player in a whorehouse, you don’t have any control over the action going on upstairs. —Robert Hughes

Do we really need a set of people whose job it is to tell the public “This art isn’t really any good,” or to tell creators “You know, you could have done that better”? Are the artists even listening? And for Christian art critics, whose religious sensibilities or personal morality might come into conflict with certain aspects of contemporary art, succeeding as a genuinely sympathetic critic might seem an almost impossible task. Maybe Christian art critics should just give up and let the artists do their own thing, whatever that is, and try to find something else to do, something that is treated with more respect?

Against all of this opposition and bad feeling I propose a three-part mission for art critics. Critics are historians; they are advocates; and Christian critics, especially, can be ambassadors. Allow me to explain.

Critics are historians

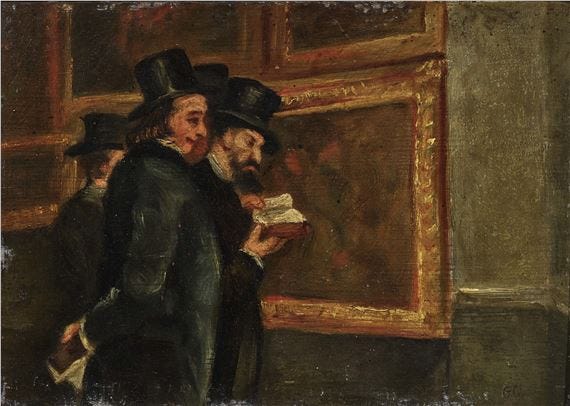

Critics can act as the collective memory of an artistic discipline, and they can make that memory available to interested art lovers. Imagine seeing cubist art by Braque or Picasso for the first time; it might be bewildering. A knowledgeable critic, closely acquainted with the history of the style—or in the case of new art, with the artists themselves—could be able to guide interested art lovers to a fuller understanding of where the style came from, what its practitioners are trying to do, and where it fits into a broader context.

Critics thus also act as gatekeepers of styles and genres. This is one aspect of the critical discipline that can sometimes annoy people—but it has its value. It might not seem fair to put art into pigeonholes but it can help make sense of what is happening. The art world can be a very confusing place sometimes, with styles, movements and isms popping up out of nowhere and producing obnoxious or perplexing pieces. A knowledgeable guide can be an asset. But suppose new art is created which doesn’t quite fit into the style boxes? That is when critics take on their second role.

Critics are advocates

The best description I know of the critic’s role as advocate comes from Anton Ego, the fearsome restaurant reviewer in Pixar’s 2007 film Ratatuoille. His glowing review of Remy’s cooking at Gusteau’s restaurant is worth quoting in full:

In many ways, the work of a critic is easy. We risk very little, yet enjoy a position over those who offer up their work and their selves to our judgment. We thrive on negative criticism, which is fun to write and to read. But the bitter truth we critics must face, is that in the grand scheme of things, the average piece of junk is probably more meaningful than our criticism designating it so. But there are times when a critic truly risks something, and that is in the discovery and defense of the new. The world is often unkind to new talent, new creations—the new needs friends. Last night, I experienced something new, an extraordinary meal from a singularly unexpected source. To say that both the meal and its maker have challenged my preconceptions about fine cooking is a gross understatement. They have rocked me to my core. In the past, I have made no secret of my disdain for Chef Gusteau’s famous motto: Anyone can cook. But, I realize, only now do I truly understand what he meant. Not everyone can become a great artist, but a great artist can come from anywhere. It is difficult to imagine more humble origins than those of the genius now cooking at Gusteau’s, who is, in this critic’s opinion, nothing less than the finest chef in France. I will be returning to Gusteau’s soon, hungry for more.

Well said, Anton! Critics can exercise a powerful influence on the perception of a new artist’s work. Is the piece worth consideration? The critic is often the one who makes that call, and their more established platform is ideal for bringing brand-new artists to the forefront. If, however, new art is too challenging or obscure for the public, critics can take on their next role.

Critics are ambassadors

A lot of twentieth-century art looks ugly and meaningless; the 21st century seems to be shaping up into the century of an art of the banal. Sometimes people can feel like the artists are mocking them or duping them; if you collect this kind of porcelain figurine, what are you to make of a sculpture such as Jeff Koons’ Winter Bears?

Christians, especially, can have a hard time understanding or coming to terms with some aspects of contemporary art. There is a sharp divide between artists, who often behave in outlandish, transgressive ways, and the institutional church, which stands for order, self-control, and propriety.

This is where the Christian critic-as-ambassador is most needed—to help bridge the divide between the church and the art world. Wayne Roosa writes about how these two worlds are very different, despite their similarities, and how “there is not enough mutual knowledge or shared literacy to comprehend each other’s languages with empathy.” He suggests that a go-between is necessary: “to have genuine conversation between these two worlds requires deliberate translators, long-suffering diplomats, and safe venues.” There is enormous opportunity for adept art critics to fill this role, providing valuable service to artists who might feel despised by the church, and to individual Christians who might not understand why artists sometimes act the way they do. I keep bringing up Andreas Serrano’s Piss Christ in this context; Serrano says that he himself is a Christian and has no tolerance for blasphemy. What would the situation have been like if a critic-ambassador representing both sides had been there for Serrano to consult before creating his notorious photograph?

Here’s a question for the Christians out there who enjoy and appreciate art and want to engage with artists. How can you be a better art critic? How can you transcend the reputation that critics have unfortunately earned, of being scowling parasites whose only contribution is to well-actually an artist’s work or make people feel bad about having poor taste? Can you approach the arts as a historian, and help people understand the meaning of an artwork in historical context? Can you act as an ambassador, working to develop relationships between artists and their potential public audience? And if you find a new artist who could use some support, can you act as an advocate? Roosa’s description of the critic-ambassador as “long-suffering” is apt: Artists probably won’t stop hating on critics right away, and the public might still feel that the critics are elitist. But with time and goodwill, I believe that the critics will, eventually, be seen for what they really are: vital players in the art scene, providing a valuable, essential resource.

MISC.

The piscine art critic, featured on this post’s thumbnail image, is from SpongeBob SquarePants, season 12, episode 249b. All of the quotes about art critics came from BrainyQuote, except for the one from Robert Hughes, who was quoted in The $12 Million Stuffed Shark, by Don Thompson. The Wayne Roosa quote is from Contemporary Art and the Church: A Conversation Between Two Worlds, edited by W. David O. Taylor and Taylor Worley.

Here is a very short, but intriguing, perspective: art criticism as peer-review process.

Here is an art critic whose approach is very intimate and involved . . . Olga Tolstunova has been cosplaying as characters from famous paintings, and the results are astounding. You should check it out.