Rusty Brown (Chris Ware, 2019)

The entirety of Chris Ware’s work could be seen as an extended meditation on the idea that, as Scott McCloud says in Understanding Comics, “we all live in a state of profound isolation.” Ware’s characters are all lonely and isolated in one way or another, and his artistry lies in his ability to get his readers into their heads with the merest inflection or gesture. His Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth (2000) expertly portrayed the emotional and psychic landscape of its painfully shy, frustrated protagonist. His recent graphic novel Rusty Brown succeeds in the same vein, tracing the inner states of six different characters, all of whom have their lives intersect on a cold and snowy morning in 1975.

The book has a rather curious structure: it is divided into four main parts, an introduction (which is itself split into two subsections) and the biographies of three of the book’s six main characters. The first part of the introduction is an experiment in parallel storytelling, with the bottom of each page focusing on Chalky White and his sister Alison, and the top primarily dwelling on Rusty Brown and his father William.

Chris Ware’s art is immaculate in its attention to detail. I know of no other cartoonist who is as careful as he is in showing exactly what he wants the reader to notice. Take this panel, for instance, from a sequence where William Brown is waiting outside the apartment where his lover lives, trying to see if she is at home. As he looks at the building, he sees this in a window:

In the passage, William’s (and the reader’s) attention is riveted to this small particle of red, which occupies less than six ten-thousandths of an inch in my paper copy of the book, but is monumentally significant to William, indicating to him the presence of his lover and triggering an extended flashback-fantasy sequence in which he imagines finally becoming honest and telling her how he feels. It is a standard tactic of Ware’s to use miniscule details to convey meaning; his work requires careful, focused attention, not only to follow the plot but to understand his character’s mental states. The inner life of his characters is known to us because Ware is a master of conveying the sort of information that other cartoonists sometimes have to leave unrevealed.

Ware’s page layouts in Rusty Brown are more formalized than in his earlier work such as Jimmy Corrigan. In this work, he predominantly employs a division of the page into a 3x4 grid, with one third of the page’s total area occupied by a large panel, and the other panels related to the main panel in ratios of 1:4, 1:16, and 1:64.

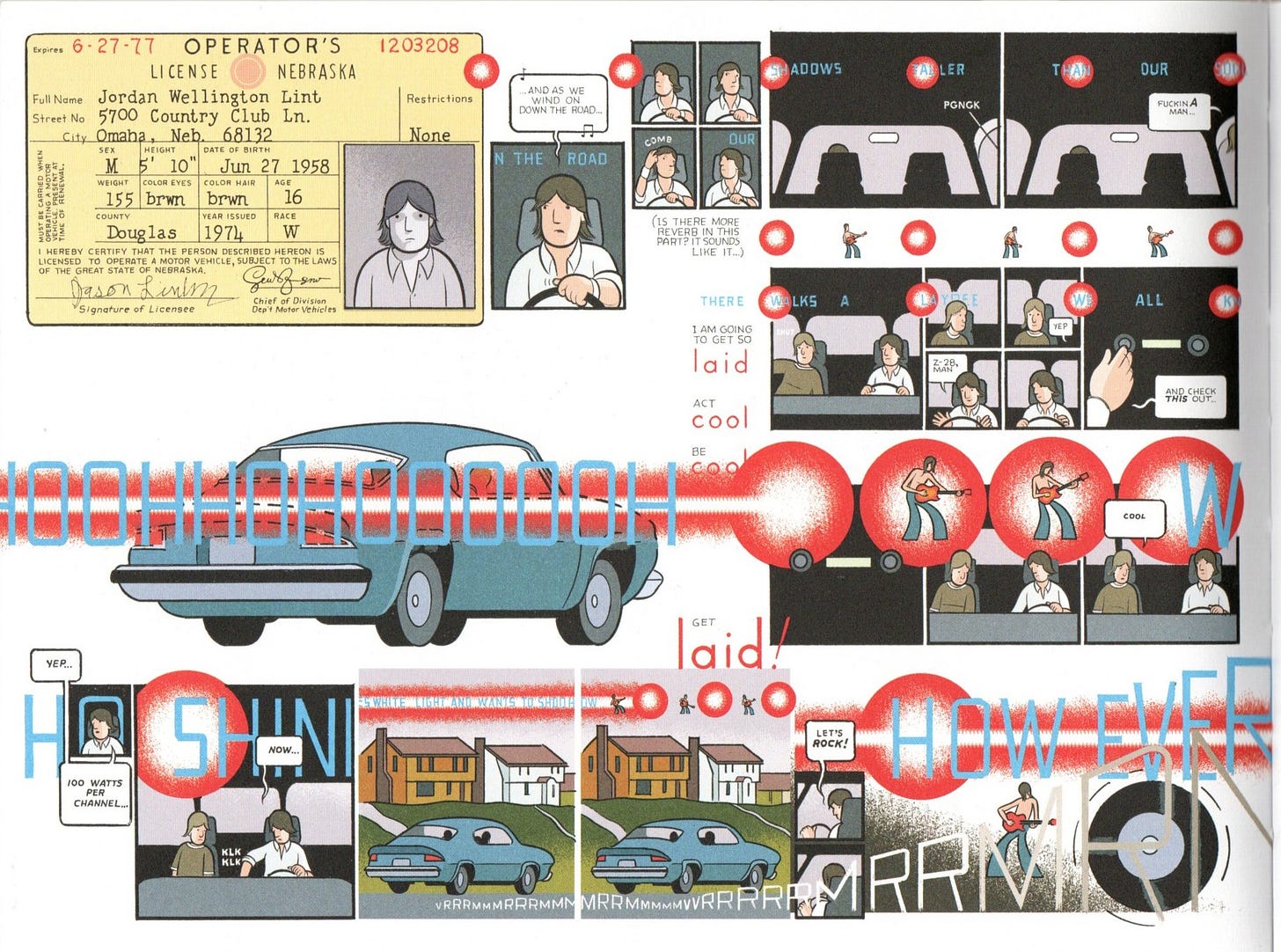

The distribution of these panels is varied continuously throughout the work. But Ware also uses much more loose, fluid, or arbitrary layouts in Rusty Brown, especially in the “Lint” section.

However even these layouts are regulated by a sense of order: notice how the page shown above is unified by the pulsing red dot (representative of the beat of Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven”!) which began as the state seal on Jordan’s driver’s license and ends as a screeching tire. Chris Ware’s concern with order and balance in his panel layouts, as well as his careful and precise linework, cause the mechanics of his art to recede into the background, allowing the story he is telling to hold our attention.

Rusty Brown and Chalky White are in the third grade, but all of the book’s characters are childlike in one way or another. Alison White is on the fence, at the age when adult obligations begin to pile up faster than childhood comforts get let go. We see Jordan Lint’s life story, from beginning to end; as an adult, he still dwells in a mental world dominated by the impressions of his childhood. William Brown is an adult whose maturity seems to have stopped in adolescence. Only Joanna Cole is a stable adult, but she is absorbed in a world of her own memories and impressions, and her social life is stunted and incomplete.

Memories are the motive force in this book, and it is the main characters’ attitudes toward their memories, rather than their present-time actions, which provide most of the delineation of their personalities. William Brown is consumed by the memory of his old flame, and the torments he underwent in pursuit of her. The end of his section of the book shows him shaving off his mustache and removing his glasses, attempting to recreate his physical appearance at the time she spurned him.

Jordan Lint’s memories take the form of short flashbacks, fleeting insights into his perception of the meaning and significance of his own past. Jordan is very self-centered, and barely shows real love for anyone, but he comes across as tragic nonetheless. “I wish I’d been good”, he says, just moments before his death, alone in bed.

Joanna Cole’s life story, shown to us from early youth to early old age, is told in a very scattered, kaleidoscopic way. Memories swirl around and interact haphazardly; it is impossible to tell if there even is a narrative present in this section of the book. The static, frequently symmetrical panel layouts in this section reinforce a sense of fierce silence. As we see Joanna Cole go through the mundanities of her life, enduring acts of microaggression and even outright hostility with quiet resignation, we get a sense that she has a great, even heroic, moral dignity; strange, then, that she comes across as passive-aggressive and petty when she appears fleetingly in other parts of the book.

It is the rare work of art which combines audacious stylistic virtuosity with touchingly sensitive storytelling. Chris Ware’s Rusty Brown does exactly that. The book’s last panel, occupying the entirety of the final two pages, is simply the word “INTERMISSION”. I will be intently watching for the continuation of this brilliant graphic novel. My expectation is that the stories of Alison, Chalky, and Rusty will be even more crushingly sad than anything Chris Ware has yet done. But it is important to remember the sadness that can occupy even the apparently successful people right next to us; the real value of Ware’s art lies in revealing to us that truth. Our inherently narcissistic egos would love to objectify everyone around us and stifle our ability to empathize. Rusty Brown tells us that the successful, yet lonely, teacher, or the awkward, nerdy child, deserve our kindness and consideration.