The proper response to an art of sorrow

Note: if you are reading this on desktop, click through to the web version of this post to see selected paintings in full-screen size. I hope you enjoy this experiment in a more immersive view of some of these wonderful paintings. I really have no idea how well this will work, so please let me know what you think!

When artists make art, they are making a public statement. That statement could range in meaning all the way from “these are pretty things to put on walls” to “this is the true nature of reality” to “this is the injustice I see in the world”. That last category has been especially prominent in the last hundred years—certainly there has been a great deal of injustice in the last century, but artists are also more fully realizing their role as truth-tellers—prophets—to the culture around them. There is a long tradition of artists using their art to publicly express their anger, sadness, despair, and grief. But what are we, as art lovers, supposed to do with a painting that seeks to expose some terrible wrong done in the world? Should we admire the painting’s aesthetic qualities? Or should we seek to embark on some action in response to the painting?

Let’s examine the gradient represented by paintings evoking outrage, sorrow, and despair. To start, there are paintings which seek to memorialize a terrible action, and which can be used to heal a community’s collective grief. The example that first comes to my mind is by Francisco Goya, painted in response to a specific incident during the French occupation of Spain in the Peninsular War.

Goya was keenly aware of the power that art could have to illuminate the horrors he saw around him during Napoleon’s invasion of Spain, and his Disasters of War series of engravings remains a potent record of his anger and bewilderment. When he painted The Third of May 1808, Napoleon’s invasion force had been expelled, and the massacre Goya portrayed was six years in the past. Goya’s painting expresses hatred for Napoleon’s army and simultaneously glorifies the solders of the resistance who lost their lives fighting for their country’s freedom; Goya’s painting desires no action from its viewers, other than sympathy and shared emotion. Since it is removed in time from the atrocity it depicts, I think aesthetic contemplation would have been an appropriate response.

The next painting on our gradient is not a memorial to a past event, but an outcry against a contemporary one.

Picasso made this painting in response to the axis powers’ destruction of the Basque town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. This is the painting that I wish I could display for you at full size—it is overpowering in real life, and its chaotic, distorted figures and composition are exactly suited to the subject. It is the greatest cubist painting ever made, and it is certainly Picasso’s best painting—nothing else of his conveys the same kind of raw emotion that this one does. But is this the right way to approach such a painting? I can imagine a critic saying, “look at how the vocabulary of cubism perfectly corresponds with the feelings that Picasso was trying to convey,” and Picasso saying “look, you don’t have to tell me that my own painting is good! Now stop analyzing the work, and respond to what I’m saying with it!” As a call to action, this work has been singularly effective; it went on tour in 1937 to raise funds for Spanish war relief efforts. But more than that, it has remained, to this day, a profoundly affecting anti-war statement; its ideological content has always been just as important as its stylistic dimensions.

These are definitely public statements about public events, meant to express a definite ideological stance about the events. But there is another kind of “public outcry” painting:

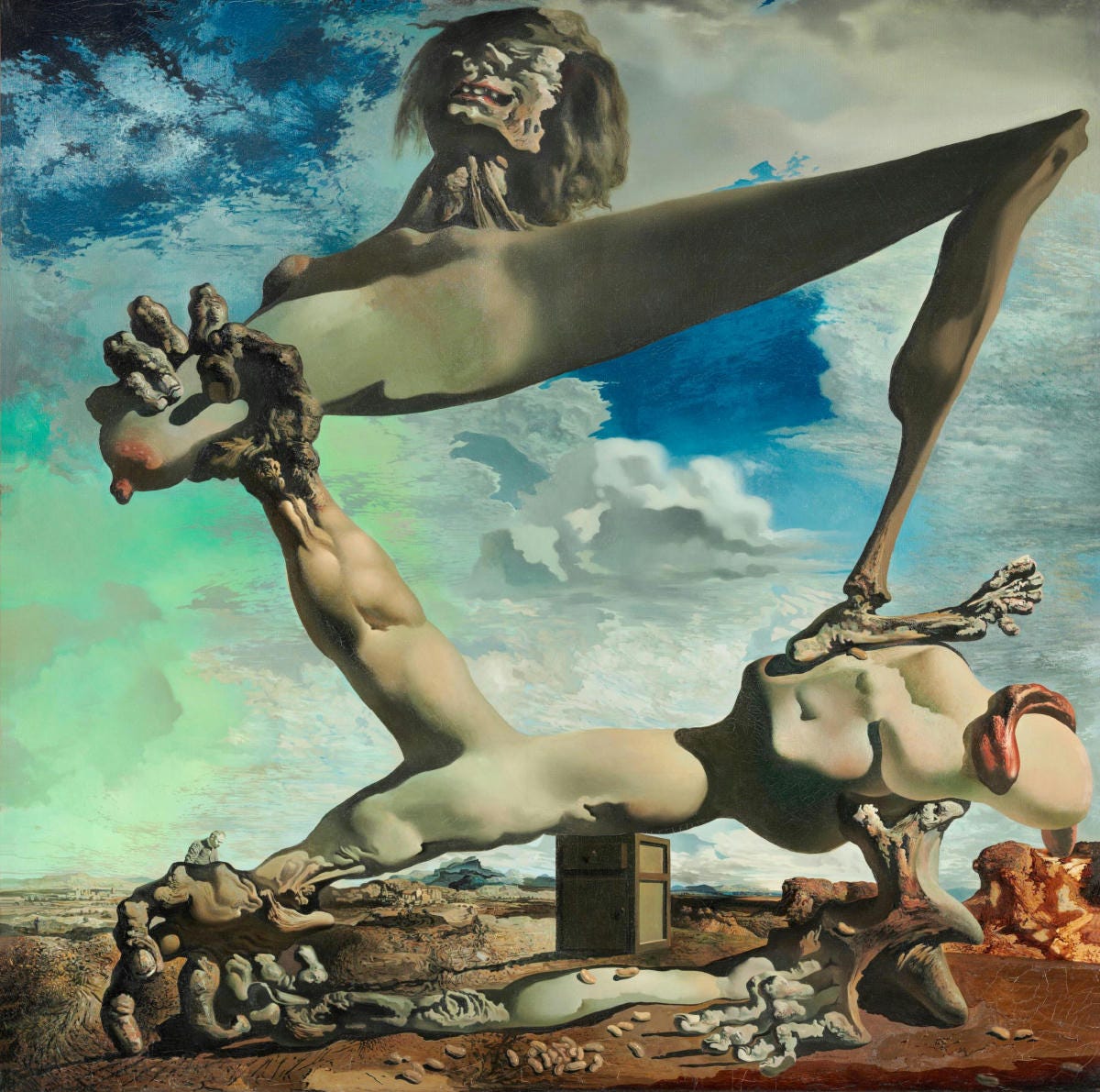

This painting is also a call to action, not unlike Guernica, but of a slightly different kind; it’s more like “hey guys, I have a bad feeling about this.” It is a “premonition”, and Dalí wants the buildup to the Spanish Civil War to stay top-of-mind for his audience; he doesn’t want his home country to tear itself to pieces like the subject in his picture. Next on the continuum is this painting:

This painting is in the realm of elegy, a mourning for what was lost. And what was lost, for Max Ernst, was not just the architecture of Europe’s cities, bombed to bits during World War II; what he saw as vanished was the European idea, the idea of a culture of decency and civility that had been shown to be hollow by the events of the war. His painting is not a call to action, unless it is a call to collective mourning.

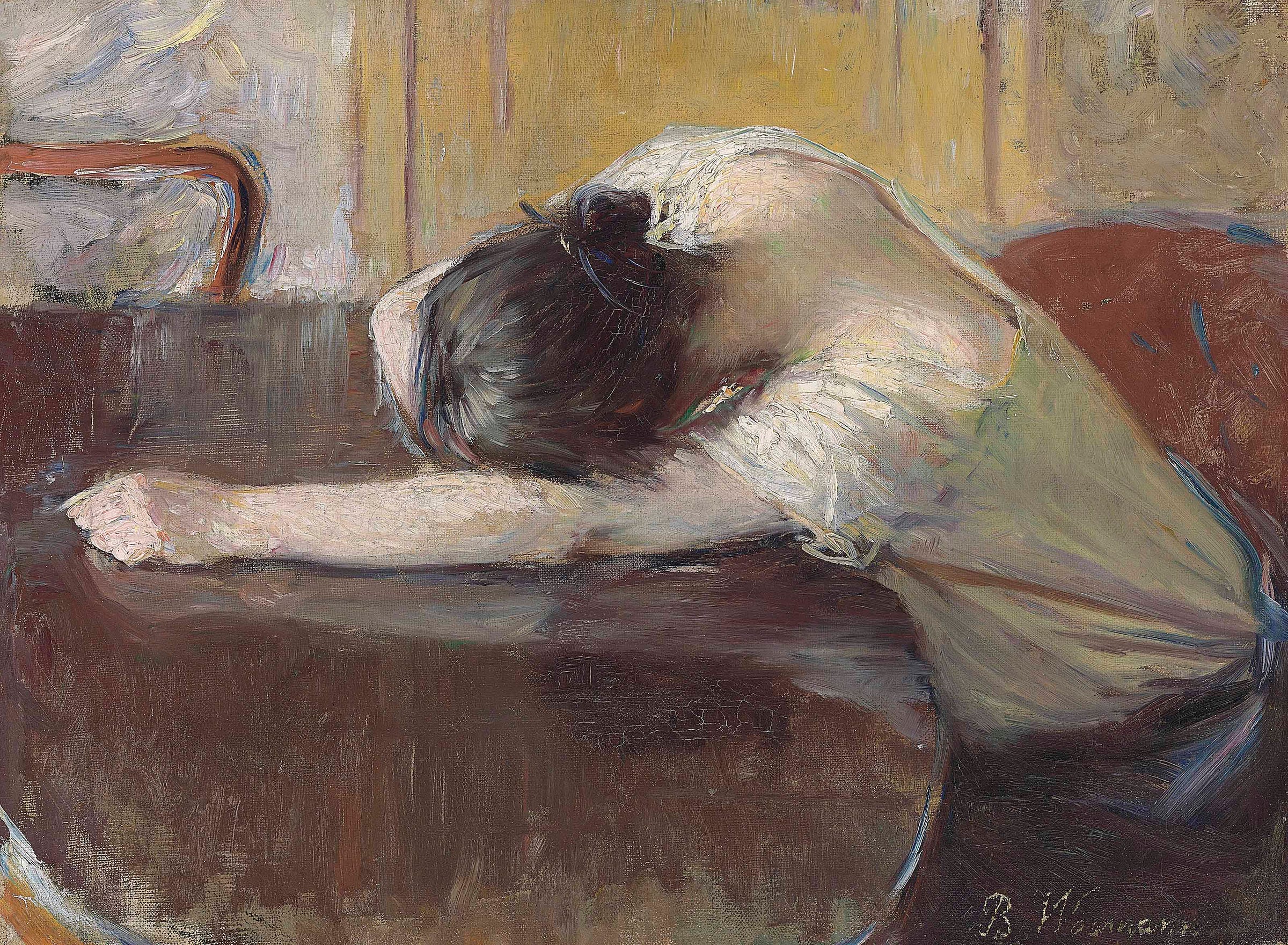

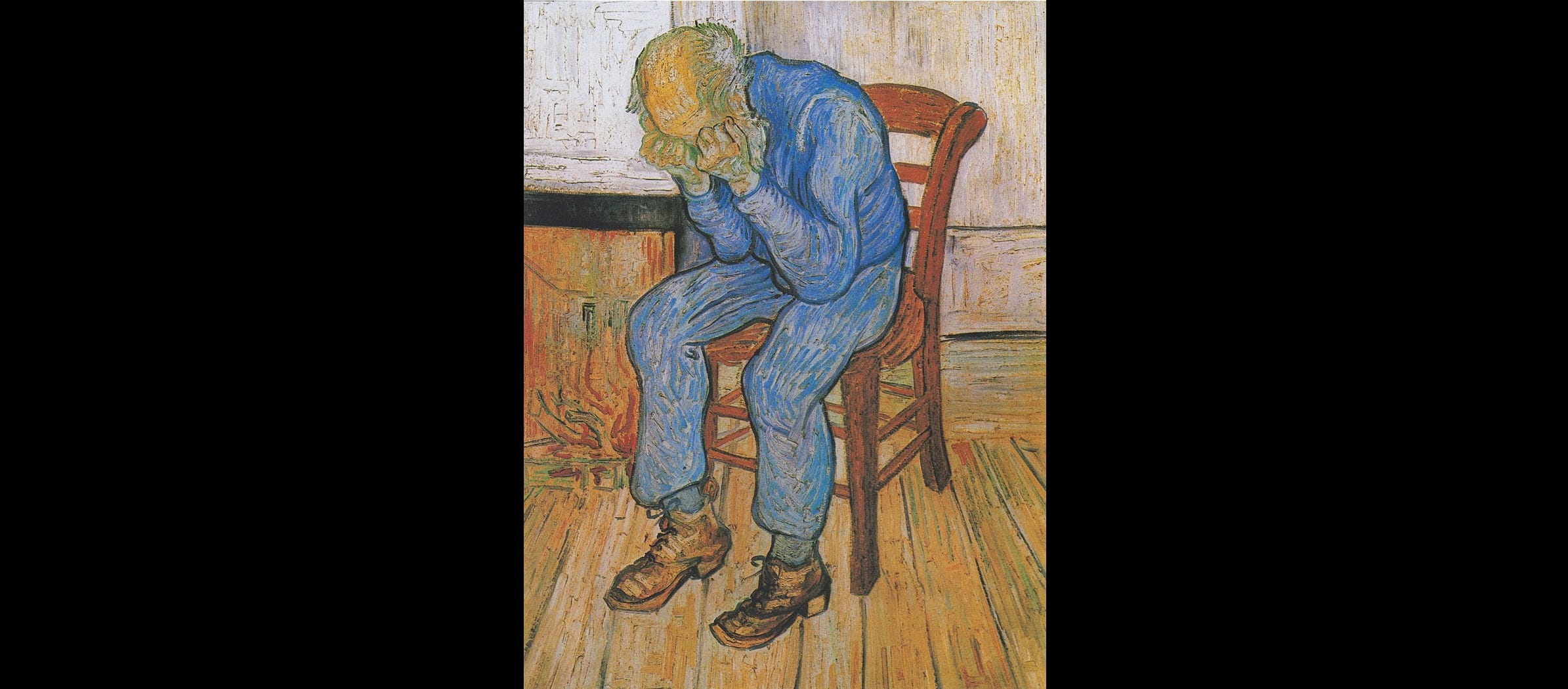

But do painters react to private grief as well as public? For some reason it seems that paintings are too public an art to be put to the service of specific, personal emotions, especially emotions of grief. However, artists can certainly express a generalized feeling of grief, and they can do it quite well:

These paintings, however, do not touch on the personal experience of grief or despair; they only evoke an emotion in the abstract. The paintings by Goya and Picasso at the beginning of this essay are speaking about specific historical events, but what, exactly, is Van Gogh’s old man sorrowing about? And there is some ambiguity—perhaps the people in Wegmann’s and Van Gogh’s paintings are simply tired. In fact, Sorrowful Old Man also goes by the title Worn Out, meaning that the painting might not be about sadness; rather, it might just be about exhaustion.

If someone you know expresses grief, sorrow, or despair, you would probably want to reach out to them in some way and show empathy. But what are you supposed to do when a public figure like an artist expresses grief? First of all, do you know it is actually their grief? Was Van Gogh painting a sad old man because he himself was feeling particularly sad at the time, or was the sad old man simply an interesting subject?

A common critical stance, when confronted with obviously sad art, is to explain the art in a very detached, objective way. “This art was created during a very sorrowful period in the artist’s life, the effects of which can be perceived in their art.” This is Glenn Holland’s take during the “Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony” scene in the 1995 film Mr. Holland’s Opus. I don’t know what the reception was like for Beethoven’s sad movement in his seventh symphony; was it recognized at the time as commentary on Beethoven’s deafness, as Holland thinks it is? Did people write to Beethoven and attempt to cheer him up? Would you have done so?

These days, it is, in fact, possible to reach out to an artist you follow on Twitter or Instagram and ask them about their feelings. I don’t know how much you can expect to get an answer, though; some artists are understandably cagey with their fans. More likely, the artist will open up about their personal emotions through the official channels of interviews.

But what should be the response to a painting like Guernica? Would it be appropriate, upon seeing such a painting, to leave everything and go fight in the Spanish Civil War? This painting about Ukraine just dropped on Reddit. Is it time to enlist?

Mostly unrelated

I’m a huge Dalí fan, and one of the things I like about his pictures are the little details that he puts in the background of his canvases. Who is this guy, moping around behind the monstrous subject in Premonitions of Civil War? And behind him there appears to be a whole city, with towers and everything!

![Guernica [Pablo Picasso] | Sartle - Rogue Art History Guernica [Pablo Picasso] | Sartle - Rogue Art History](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Nzpw!,w_5760,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa0ff0e87-fc6e-431f-b811-12fd5f89852d_2667x1000.jpeg)

Enjoyed this, William. Interesting how the cubist and surrealist portrayals of war pack more of a gut-punch (at least for me) than more traditional, classical depictions. Even the Goya, while more traditional, is powerful because of the exaggerated, almost mask-like expression he gave the central figure.

Great read. Really curious to hear your interpretation of the man Dali added in the background.

I’m not good at interpreting these things but maybe he put the man in between the city and the monster as a way to remind people to protect their city from the monster. The relative size of the monster compared to the man might also be his way to compare the relative damage that war can bring to each individual.

Or maybe I’m completely off 🤣