The Era of Collaborative Composition

Note: this essay is about music in the western art music tradition, which I will more-or-less arbitrarily define as not including folk music or community-based popular music making, but which will include things like serious art rock. The line between serious and popular starts to get blurry in the last quarter of the twentieth century, when recorded music of all kinds began to supplant more traditional paper-score music as the locus of interest for serious composers. There are still people working in the tradition and with the methods of the Common Practice Period, but they do not receive much attention, and, arguably, do not constitute the mainline of musical composition today.

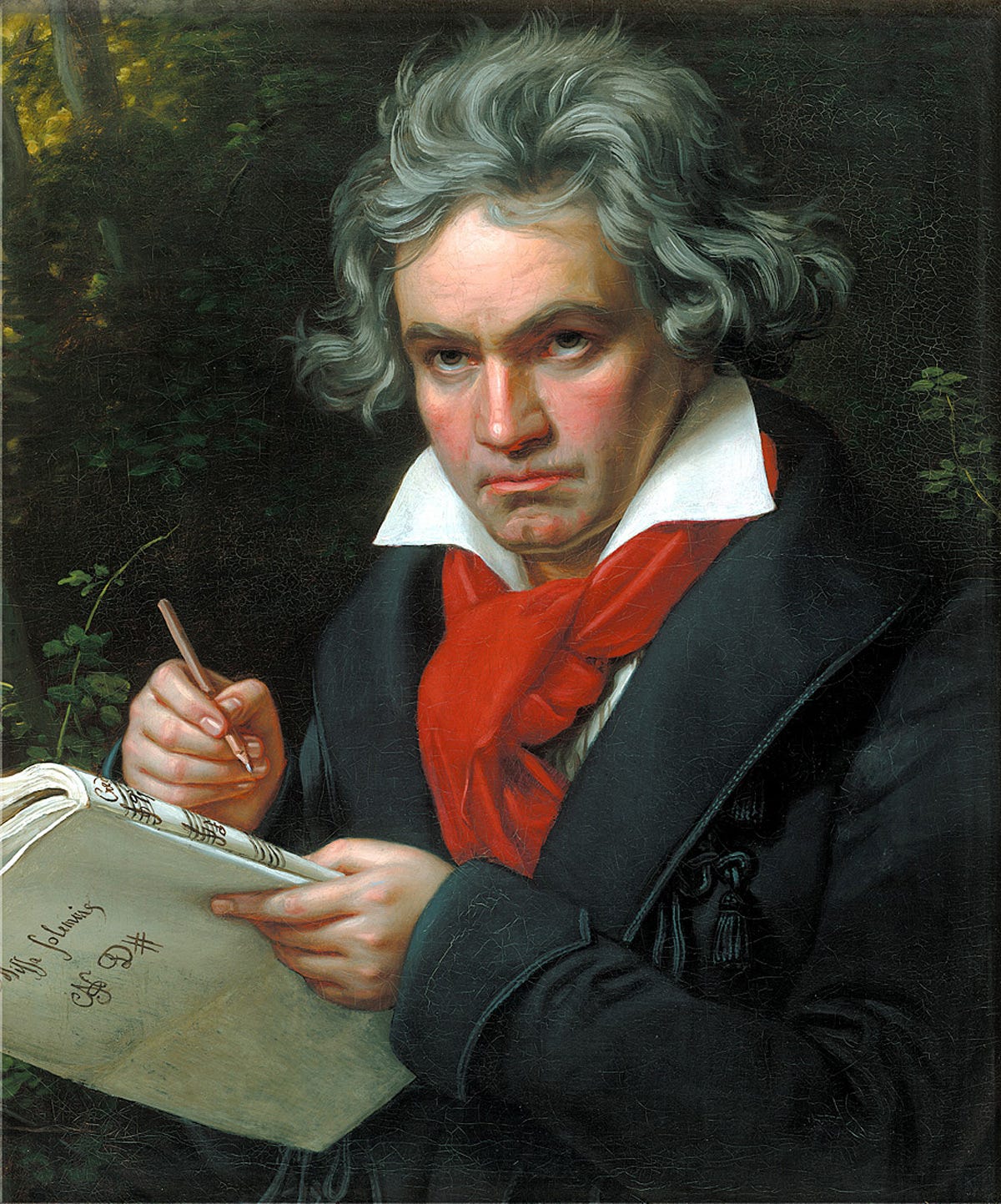

For most of the history of western composed music, the composer worked alone. We can all probably conjure up a mental image of some wild-haired musical demigod, setting down works of Great Art with his quill pen and contributing to the Great Tradition, and doing it unaided, the results being the proper outflowing of his solitary genius.

There were exceptions to this pattern—opera, in particular, has a long history of close collaboration between the librettist and the composer of the music, although power in that relationship usually flowed down from the composer, who would alter or modify the librettist’s words to suit the music, rather than the other way around. Works were frequently commissioned by virtuoso performers; in such cases the composer would often work closely with the performer, ensuring that the music would show off the virtuoso’s technical skills to best advantage. But aside from these collaborations the composition of the music itself—the melodies, the harmonic and formal structures, and the instruments used —was always accomplished by one person, working alone. I know of no musical composition from the western Common Practice Period which contradicts this assertion.

This image of the solitary composer began to be modified in the mid-twentieth century, with the advent of recording technologies, and with the changing attitudes toward popular musical idioms. The tipping point was the release of The Beatles’ album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in 1967. Widely regarded as transcending the genre of rock and roll, this album incorporated techniques developed by avant-garde European composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen and Pierre Schaeffer, who were exploring the capabilities of the recording studio in an art-music context. More and more rock musicians aligned themselves with the new aesthetic of artistic ambition, and they were able to bridge the divide that had previously held rock to be mere popular entertainment, with no artistic pretensions. And thus arose a new species of serious composer: one who worked within the context of a group. The individual composers in a band would release their compositions under the band’s name; some groups even rejected individual compositional credit entirely, crediting their compositions to the band itself.

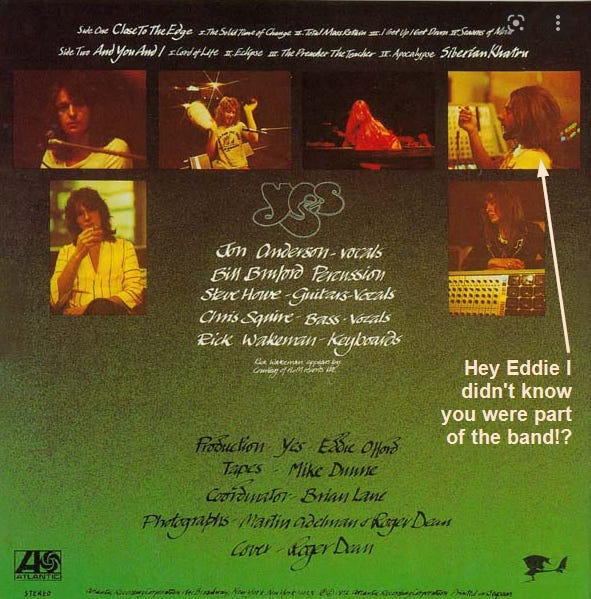

Rock musicians still needed the support of the studio personnel who facilitated their compositional endeavors, and sometimes that debt would be deliberately acknowledged; on the back of Yes’ Close to the Edge, engineer Eddie Offord is pictured in a manner which equates him in importance with the rest of the band.

(Interesting side note: this tendency toward collaborative composition seems to directly correlated to a reduced tendency for the composer and the performer to be different people. Rock composers almost always did the performing of their music in the studio.)

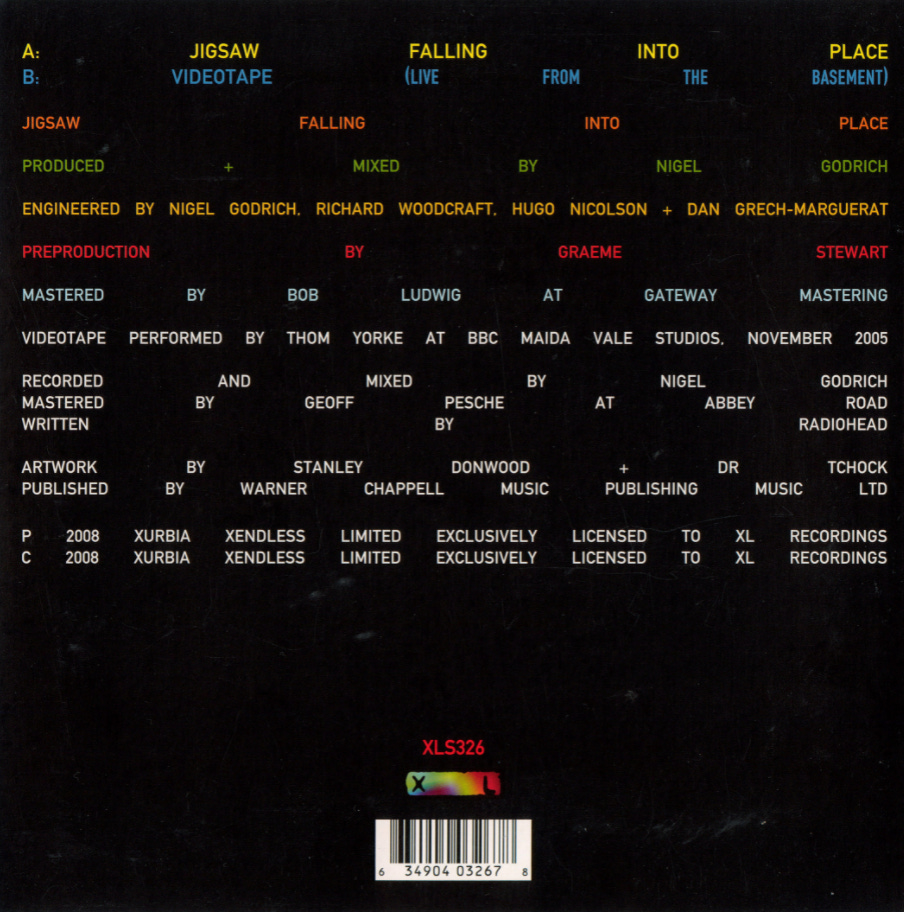

And now we are seeing a swing back toward the old days when composers worked alone. Home studios have always been a thing; musicians like Brian Eno and Trent Reznor, however, were the exceptions in an artistic culture that primarily showcased groups of musicians composing together. But now, with the availability of extremely good quality home recording software, musicians don’t even have to work in a studio environment, with engineers and producers; they can realize whatever sounds they want right at home.

In the last fifty years, there has been a proliferation of subgenres of recorded music, and some are more likely than others to be typified by solo composers. Ambient music, techno, and the freakier kinds of metal seem to feature solo composers more often than radio-friendly pop or hard rock. Jazz has always maintained an ethos of collaborative creativity (and jazz recordings are almost always recordings of a live performance, whether captured in the studio or otherwise). Hip-hop still features the DJ / MC dynamic.

Do different artistic disciplines skew one way or another on the solo / cooperative spectrum? Film and architecture are eminently collaborative pursuits, with architects in particular seeming more like curators than creators. Painting is the exact opposite—at least, it has been since the abandonment of the Rembrandt-style workshop model, where the master put in the people’s faces and other important elements, and the apprentices put in the trees and sky. Literary creations are almost always the product of a single mind, but books often have an editor with considerable powers. It seems to me that, the more physically present a work of art must be, the more likely it is to require the efforts of multiple co-creators (with painting being the glaring exception).

So how do we explain the rise, and subsequent decline, of the collaborative musical composition? Perhaps it is due to the physical presence of the album—first as vinyl, then as CD, with extensive cover art and liner notes. I don’t know why this would have any bearing on the musical composition itself, but the correlation is uncanny—as streaming services began to dominate the music market, rendering unnecessary the possession of a physical album in order to access the music, artistic collaborations grew less prevalent. They are certainly still very much in existence, but solo musical artistry is staging a significant return.