When Arcade Fire released their third album, The Suburbs, in 2010, the band’s singer Win Butler claimed that the album “is neither a love letter to, nor an indictment of, the suburbs—it's a letter from the suburbs.”1 That might be so, but it’s hard to believe that he didn’t have a negative opinion about suburbia when he wrote the lyrics to the band’s greatest record. Whether you agree with Butler or not, The Suburbs is well worth a listen, if only as a masterful example of how rock music can establish and communicate an emotional viewpoint. So: let us go then, you and I . . .

The overall tone of the album is one of disappointed hopes and disillusionment—as if the suburbs were a promise that never came true. Butler et al. inhabit the perspective of people who grew up in and around the suburbs, and that experience overshadows their dreams, hopes, visions, and plans, coloring their entire outlook. On the surface, the suburbs seem like a nice place to stay, but in reality they are only a place of transition—people move to the suburbs to have kids, then the kids move away as soon as they can. According to Arcade Fire, the suburbs don’t have a continuous future. They are isolated, small, and inward-looking; living in one can feel like being in a trap.

The album’s first song sets the tone quite well. It starts with a jaunty, syncopated piano, full of the promise of happy times—but the true mood of the music is bleak and gray. The song’s first line seems like it’s trying to establish a feeling of happy nostalgia: “In the suburbs I learned to drive.” But right away that mood is darkened; the next line is “they told me I would never survive.” A very jarring literary juxtaposition! The two ideas are tied together with the next line: “grab your mother’s keys, we’re leaving.” Here Win Butler is exclaiming that, though he might be fated to never survive, he’s going to try to avoid his fate if he can. The whole album is full of such avoidance: running away from, maneuvering around, coming to uneasy terms with the idea of the suburbs.

Win Butler’s voice, which rarely reaches above mezzo-piano throughout the entire album, is perfect, conveying, with flawless precision, a mood of pain, despair, sadness, wistfulness, and resignation. The songs on the first half of the album are grand, mostly loud, filling vast spaces with their pent-up and frayed emotions; rarely does such joyous-sounding music depict such deep, poignant sorrow as this (the exceptions being certain bands and tracks from the Montreal scene where Arcade Fire had their genesis; Godspeed You Black Emperor’s vast, sprawling “Storm” being the best example of a piece with similar mood.) The latter half of the album is somewhat more muted in comparison; instead of frustration we have nostalgia. But it’s a strange nostalgia, tinged with a wish that things could return to a state that they never really inhabited at all.

Rock is allegedly an art of rebellion, of wild abandon, and what does it mean for rockers to discuss the suburbs, of all places? What do the suburbs signify? As an environment of order, placid domesticity, and conformity, the suburbs seem like a strange landscape for rockers to explore. But isn’t it true that in the suburbs is where most kids first encounter rock music? Thinking about the suburbs brings two other songs to mind. The first is Bruce Springsteen’s “Born to Run”, which contains the lyric “sprung from cages on Highway 9”, a reference to the New Jersey exurb where Springsteen grew up. “Born to Run” matches the glorious yet fractured tone of the fifth song on The Suburbs, “Empty Room”, which reaches its climax in the line “my life is coming but I don’t know when”—appropriately mirroring the themes of Springsteen’s famous song. Is it possible for anyone to grow up in the suburbs, and not feel trapped? To get anywhere, you have to drive; what if you aren’t old enough to do so?

The second song is Sonic Youth’s “The Sprawl”. The title is a reference to William Gibson’s Neuromancer trilogy of novels, parts of which are set in an enormous megacity stretching from Boston to Atlanta. The Sonic Youth song doesn’t overtly reference Gibson’s novels in the lyrics, but it does contain this evocative, enigmatic verse:

I grew up in a shotgun row Sliding down the hill Out front were the big machines Steel and rusty now, I guess Out back was the river And that big sign down the road That's where it all started

This seems to be more of an industrial suburb, not so much a residential enclave, that Kim Gordon is singing (or sprechstimme-ing) about. And unlike Arcade Fire, who seem to have a problematic relationship with the suburbs, Gordon seems rather indifferent to them—the suburban landscape of wasted industrial parks is just . . . there. This is important to remember: some people, such as Gordon’s narrator, were raised in the suburbs and don’t have any resentment or difficult feelings about the experience; Arcade Fire’s perspective is not the definitive one.

Teenagers aren’t the only ones who might feel trapped in the suburbs. Win Butler sings about the plight of the contemporary male in the album’s third song, “Modern Man”. Early-21st-century society sometimes seems set up to make the life of modern men a life of frustration and disillusionment. All around us, there are images of men doing heroic deeds—superheroes, warriors, etc. But what does the modern man find himself doing most of the time? “So I wait in line, I’m a modern man,” Win Butler poignantly sings, “like a record that’s skipping, and the clock keeps ticking.” Leonidas was a man, and he fought the hordes of Persia; today’s man fights the crowds at the grocery store. A modern man is filled with the desire to do deeds of greatness. But in the suburbs, what is there left to accomplish? Has the duty to conquer, to protect the defenseless, and to secure food and shelter for his family been reduced to unplugging a stuck toilet, shoveling snow, and setting mousetraps? Sometimes, pent-up frustration boils over into acts of senseless violence— “want to break the mirror of the modern man”, Win Butler sings, but his pseudo-manly act of aggressive dominance is made all the more pathetic by how impotent it really is.

It’s hard to believe Win Butler when he says this is merely an observation from the suburbs, with no ideological content. Maybe the conclusion is foregone. Is there any voice out there saying that the suburbs are worth living in? I’ve got to believe that there are people who actually do like the suburbs—otherwise no one would live in them, right? While doing research for this essay I came upon this quote from Le Corbusier.

The cities will be part of the country; I shall live 30 miles from my office in one direction, under a pine tree; my secretary will live 30 miles away from it too, in the other direction, under another pine tree. We shall both have our own car. We shall use up tires, wear out road surfaces and gears, consume oil and gasoline. All of which will necessitate a great deal of work . . . enough for all.2

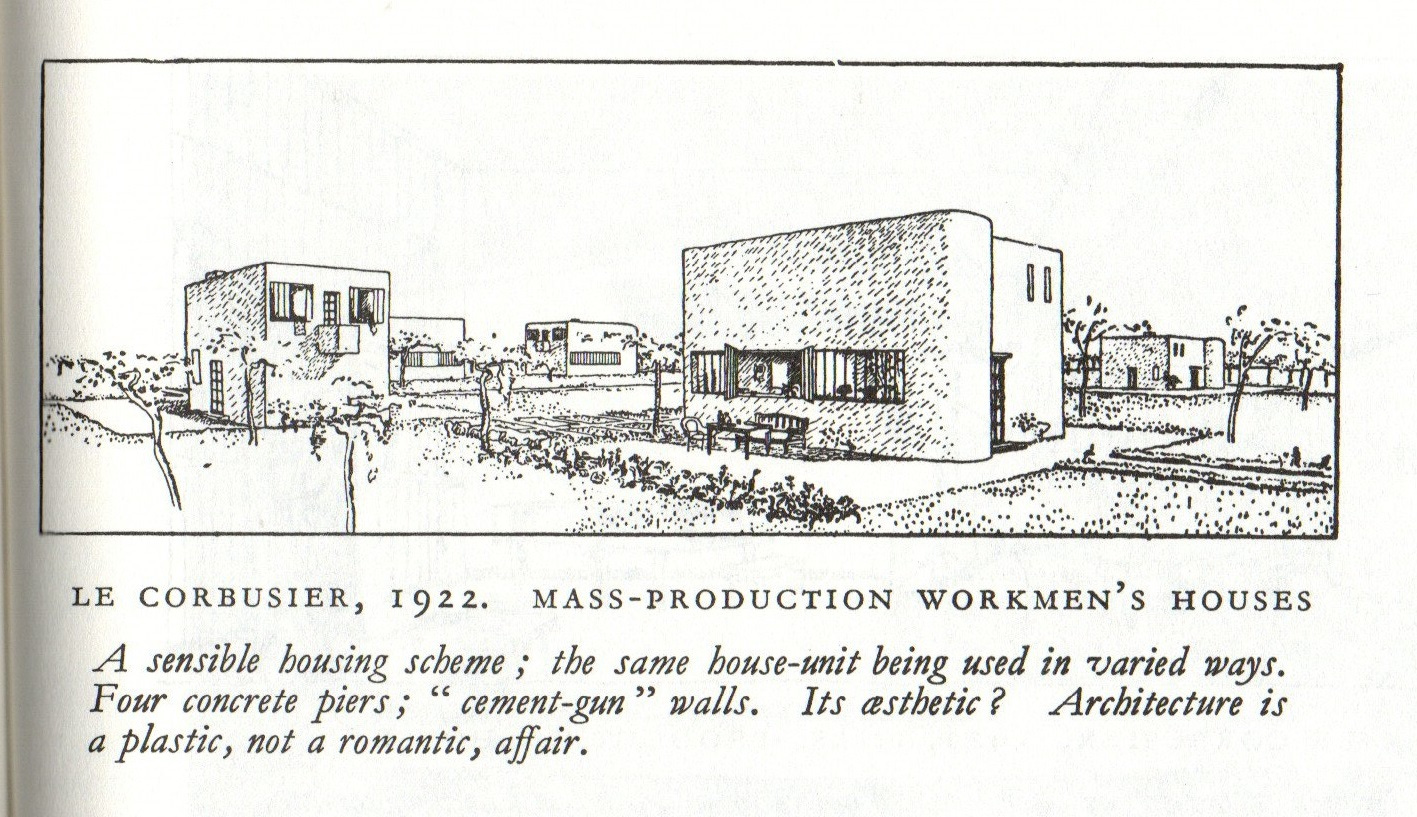

So, at least one “respected” voice is advocating for suburbia. But Le Corbusier was also the one who wanted the common people to live in little identical cube-shaped houses like this.

From Le Corbusier’s vision, it’s not much of a step to here:

What do the suburbs represent, anyway? Deep down, they embody a regimen of control and standardization that flows, not from the people who actually live in them, but from someone else—an architect, a city planning commission, etc. The suburbs represent an ideal of a perfectly ordered safe place, free of irregularities and with minimal risks. Whether the pursuit of such an ideal is good for human flourishing is an open question.

In 1957, Betty Friedan was surveying her former Smith College classmates and realized that there were many who couldn’t stand the idea of living in the suburbs surrounded by domestic appliances. “Isn’t there something more to life than this?” they wondered. Friedan’s research eventually led to the publication of The Feminine Mystique, and the full integration of women into the modern workplace, freed from the stultifying life of a suburban housewife surrounded by labor-saving machines which also saved her from the need for thought or decision-making. And Betty Friedan’s goal of liberating women had been accomplished . . . or had it?

Because at the same time that the feminist movement was breaking apart the traditional role of women, corporations were increasingly moving their offices out of the city core and into edge cities of office parks; suburbia had, in fact, assumed the role of the old downtowns, had eaten them up and digested their substance.

This is the setting for the last full song on The Suburbs, “Sprawl II (Mountains Beyond Mountains)”. Régine Chassagne gives the vocal performance the whole album has been building up for: an emotionally-charged anthem of despair and disillusionment that aptly corresponds with Win Butler’s nostalgic frustration. She gives the album’s most raw and direct statement of bruised emotions: “These days my life, I feel it has no purpose, but late at night the feelings swim to the surface.” From her office window she can see the lights of the city core simultaneously calling her and pushing her away, and she wonders “if the world's so small that we can never get away from the sprawl.” It is a transcendent summation of what the sprawl means to the heirs of Friedan’s ideological mission: the sprawl, repackaged as an office park, is just the same trap in a different disguise. “I need the darkness, someone please cut the lights,” Chassagne sings. For her, the only way out of the trap is death. And if that’s not an indictment of suburbia, I don’t know what is.

NME Magazine, 7/31/2010

From Corbusier’s The Radiant City (1967), quoted in Andrés Duany, Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream.

.

I'm not sure there IS an ideal way to organize people. Each choice will up its ups and downs. This isn't to say it's pointless to debate, but that we need to decide why another way is better, not just why we don't like the current reality.

Of course, art isn't debate. And The Suburbs is still my favorite AF album.