We Lie To Ourselves Using Images

Pictures are, by their very nature, meaningless. They have no text, no propositional content at all; as James Elkins points out in Why are Our Pictures Puzzles?, “pictures have no words, and therefore they do not say anything.” Images—paintings, drawings, photographs—are just there, presenting themselves to us but not telling us anything about how to think about them, or how to respond to them. When you look at a painting on your wall or at the museum you are doing most of the interpretive work yourself, with little aid from the image.

All this is true, but . . . we all know how powerful images can be. Images can convey emotional states, sometimes powerfully, disturbingly so; they can persuade us and enlighten us, and help us comprehend reality; and they can prompt us to believe certain things about the world around us, and even about our own selves. One of the most intriguing, and powerful, ways that images can communicate to us is by representing an example of something that we wish for or desire, thereby inciting us to desire it more: images can be aspirational.

Several of the paintings from the Dutch Golden Age could be read this way. Consider:

In these views of Dutch domesticity, the artists are showing us a sanitized, orderly, ideal image of what home life ought to be. Everything is where it belongs; the guests are smiling and laughing; the windows are clean, the courtyard is swept and the servants are properly industrious; and the baby might have spilled her drink but she isn’t crying about it. What are these pictures telling their intended viewers about what it meant to be Dutch in the 1660s? Having recently achieved their independence from the Spanish Habsburgs, and at the helm of a trade empire that stretched around the world, the Dutch found themselves at the time in an enviable economic and political position. These pictures serve to prop up a national mythos of staid prosperity; seeing these pictures, you would have little doubt that the Dutch had solved for temporal happiness. And if you, as a seventeenth-century Hollander, were the least bit unsure how to go about realizing that national promise, you had images like these to remind you of what that happiness should look like—house in order, servants busy, children quietly playing to the side. Get the message? This is what you are supposed to want.

Take a good, long look at this painting, by the greatest artist who ever lived (in terms of market share, at least).

It is certainly an idealized, romanticized image of home. Thomas Kinkade himself said, “As I worked on this painting, I imagined my own family living in this beautiful setting.” Kinkade certainly could have bought a dozen little cottages like this if he had wanted to—but what does the painting say about what should happen in these kinds of houses? Notice that, even though the weather is splendid, all of the people are inside the building—the yard is empty except for two prowling cats, and all the windows, from the attic crawlspace on down, are bursting with light. Everyone must be having a good time in there! Wouldn’t you like to join them? Home is Where The Heart Is—and, presumably, if you are the kind of person who hangs this sort of picture on your wall, you want your home to be like the home in this painting—a happy, love-filled, hearty place, where everything is well-lit, comfortable, and cozy.

And that—cozy—is where we find the ultimate in aspirational imagery. But we will have to leave the world of art criticism and wade deep into . . . Instagram.

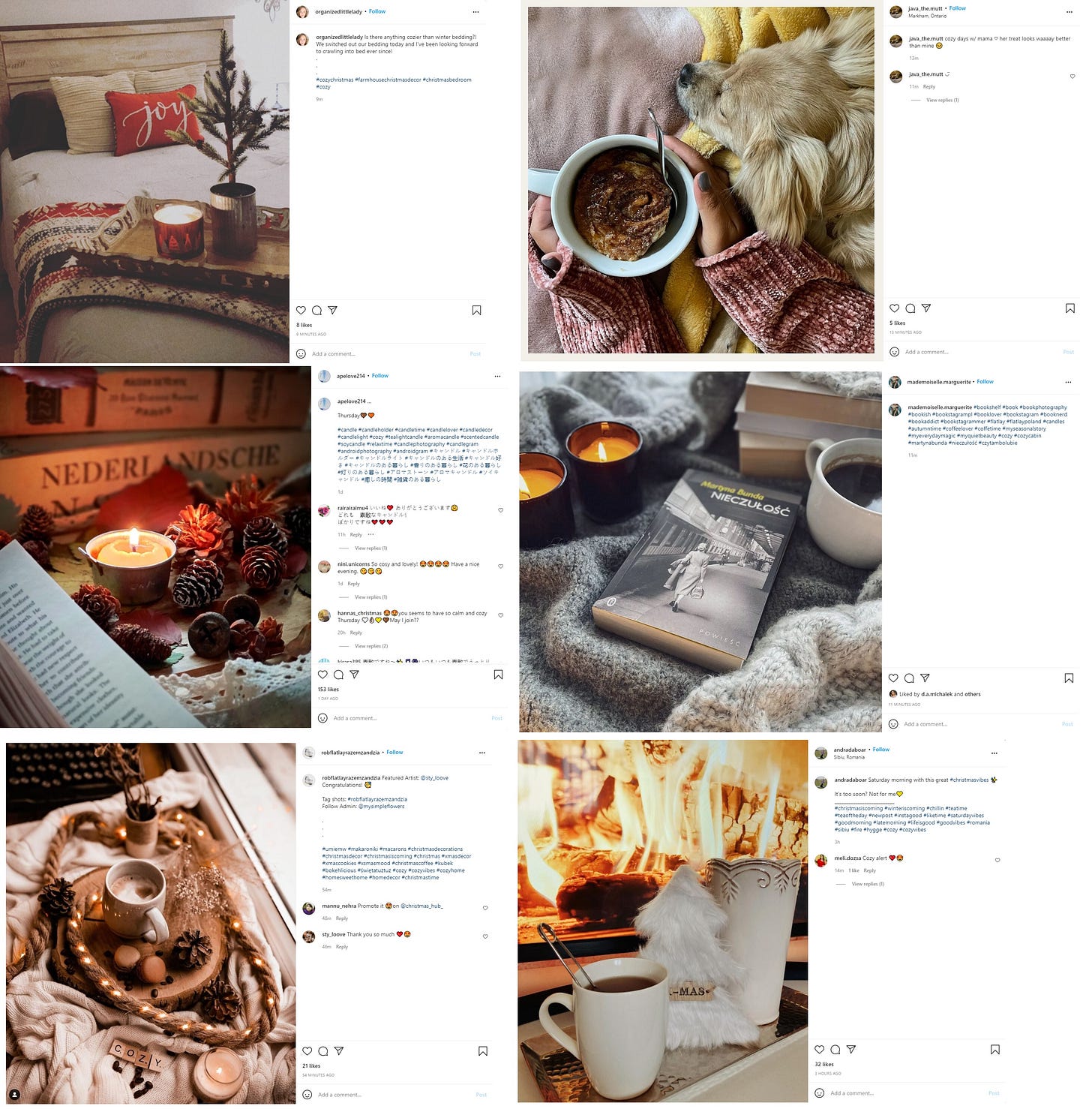

The idea of cozy is heavily laden with aspirational undertones, and it is also an idea that lends itself perfectly to visual representation. Unlike happy, nice, or joyful, cozy is a state of being defined by objects: candles, hot chocolate, pillows, knitwear. And who wouldn’t aspire to an ideal of coziness? Cozy means “perfectly content, no worries or problems, safe and warm, etc.” At about this time of year, social media begins to spew out heaps of perfectly-curated, idealized images of the cozy life, images which uncannily replicate the ideological aesthetic of the Dutch Masters with a 21st-century vocabulary—everything in place, good vibes only, this is how things ought to be. (Except, maybe, can we get that lit candle off the bed!?)

There is a danger with looking at aspirational images. It is easy for covetousness and envy to develop when scrolling through pictures of cozy places on Instagram, but it is even more dangerous if you start to think that the cozy image is an accurate view of reality. These pictures can take hours to stage—shopping online for the right accessory, setting up the lighting, and all the rest—yet the pictures might lead you to believe that yes, this is what someone’s real life actually looks like.

Something is deeply off in these Instagram / Pinterest evocations of cozy. Abstracting the props from the messy realities that make up a full, well-rounded life is a form of self-deception; as Kathryn Jezer-Morton points out in her recent essay “Is cozy season a cry for help?”, “Instagram does a bad job of representing the actual experience of being human.” Yet people keep looking at these images, deluding themselves into thinking that what they see is real. This sort of self-delusion is also happening in the paintings from the Dutch Masters—Vermeer, de Hooch, et al. were helping their audiences to lie to themselves about reality.

Certainly, a person who admires the Dutch Masters might be doing so for technical reasons alone (the paintings exhibit a masterful command of the medium of oil painting); or they might just think the paintings are pretty, and like looking at them. Elkins is right when he claims that images have no propositional content at all. But—this doesn’t stop us from giving them meaning. And we must be careful how we do so.

Misc.

I stumbled upon an interesting Substack newsletter called Design Lobster. the intended audience is professional designers, but it looks like it would be useful for any practicing artist—or anyone interested in why things take the forms they do. The newsletter asks the kind of questions that all serious artists should be asking: how do my choices affect the message I am sending with my art? I’ve been enjoying it; you might also. This essay, about the design of the buttons in Apple’s operating system interface (!), was exemplary.

Reading art is often 'harder' than reading a book.

This was a great read. Loved how you drew the parallel between aspirational imagery from the past and the present, and how they’re still deceiving and don’t accurately represent reality. I never thought about it from your perspective until now. I tended to quickly cast blame on new technology for the modern Instagram craze of creating deceivingly perfect pictures. It goes to show that our tools are just tools, whether it’s just a brush or a phone. It’s our flawed perceptions/standards that are the problem.

Thank you for expanding my thinking! 🙌