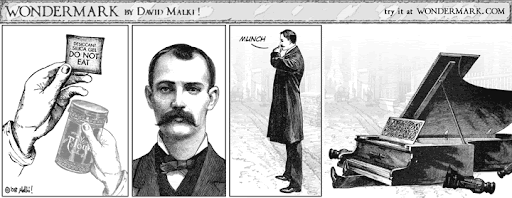

Who hasn’t made up their own original dialogue to pre-existing images? Print newspapers had a long history of running caption contests; Mystery Science Theater 3000 only validated something people have been doing at the movies probably since film was invented; and I’m sure I’m not the only person who has amused themselves at the art museum by making up goofy backstories to the pictures. Juxtaposition of new words to pre-existing images might be inherently satirical; it certainly is in Wondermark, David Malki’s hilarious and profound mashup of Victorian-era imagery and 21st-century zeitgeist.

The architecture of Wondermark is simple: Malki takes public-domain images, edits them into (mostly) straightforward collages, and writes dialogue for the people or animals depicted therein. The comic features almost no repeating characters, and extended story arcs more than four or five episodes long are extremely rare. With no relationships between characters to maintain, with no internal verity or consistency to be expected, Malki is free to make his characters do or say whatever he wants. This can range from the mundane through a spectrum of hilarious bizarrerie. Malki’s preoccupations have changed over the eighteen-year history of his comic; in the first few years, sex was referenced much more overtly, there were more cats, and there was also a higher degree of morbid or gallows humor evident.

In Wondermark’s middle period (which I will arbitrarily define as comics numbered approximately 600-800), complicated, steampunk-esque mechanisms were frequently deployed to add visual oddity to the strip, and this could be considered the high point of the strip's visual humor. Since then, Malki seems to have settled into a predominant interest in commentary on contemporary society, how it works, how it thinks, how it thinks about itself, and the lies it tells itself so as not to feel depressed all of the time. Wondermark’s characters might look like they are from the late 19th century, but they exist in the contemporary moment; they have mobile phones, Facebook accounts, and all the rest. The perspective they employ is that of a desk worker who keeps tabs on the surrounding world and who is more-than-usually talkative about their own motivations and thought processes.

Malki does not explore the possibilities of the webcomic medium as much as he could. There are probably less than five wondermarks which feature animation; less than fifty which require the reader to scroll down to read the whole thing. Images are not the main point for Malki, even though he has said that assembling crazy collages of machines might be his favorite part of making the comic. The real point is his satirical take on modern American culture. Almost the entire corpus could be put into two buckets—“people are stupid” and “people are crazy”—with the rest just being flat-out freaky-weird. But even these are quite often some absurd exaggeration of an aspect of modern life. Have you ever had someone in your life judge your valuation of them by your interest in their hobbies? There is a wondermark for that. Have you ever felt the actions of corporations can only be explained as completely arbitrary caprices? There is a wondermark for that. Perhaps Malki’s crazy machines are to be read as a metaphor for the wacky, mixed-up, liable-to-explode-apart-at-any-moment state of contemporary culture. Perhaps.

The real value of Wondermark lies in its reminding us to not get too invested in our own way of doing things—showing us that, for just about every action we can take, there is a perspective where that action seems ridiculous. And that’s a good thing; no created being has a right to be taken 100% seriously all the time. Perhaps that is why men rarely get the best of women in an argument in the comic.

Malki exercises admirable restraint and does not ever, to my knowledge, comment about his own strip in the strip itself (although some of his guest writers have done so). This is not to say that Malki doesn’t care about the medium of comics. In 2005, he wrote a series of critical essays about newspaper comics, taking a mostly dismissive tone and encouraging his readers to not stand for such twaddle. His essay “Recontextualization” from that series provides an interesting foil to the entire body of Wondermark proper; recontextualization is what Wondermark is all about, the antique images given new surroundings and made to comment on our own absurd time. The tension between the fauxtopia of an idealized Victorian era, presented through images, and the wry, ironic stance Malki takes in the strip's dialogue, is the motive power that drives much of the strip’s humor. Would Malki say that idealizing the past distracts us from our own problems? That is hard to answer. Right now, he probably would say, our problems can’t readily be fixed—we're just too busy laughing at them to do so.