A completely inanimate object

What counts as art? Are there things which are well-made, and which exhibit a high degree of craftsmanship, yet which are still not “art”? What are “the fine arts”? Surely we can all agree that music, painting, and sculpture fall into that category. What about architecture? What about photography? What about dance? Should a line ever be drawn between “art” and mere “craft”? Can some aspects of crafts such as furniture design be artistic, yet not be art?

And what about “high” versus “low” art? Does sculpture count as more of an art than flower arranging? Is jazz more of an art than rock? Is there more art in a sonnet than in a limerick?

What about John Conway’s Game of Life? Is it art?

In 1970, John Conway, a mathematician and computer researcher at Cambridge, published a paper in Scientific American as part of Martin Gardner’s widely influential “Mathematical Games” column. In this paper Conway described a game he had created the previous year. It is a zero-player game; a person plays it by creating a set of initial conditions and watching developments unfold. As with many of the world’s greatest games, the rules of this game are absurdly simple. Imagine a piece of graph paper. Color in some of the squares; they are called “live.” All the uncolored squares are “dead.” Then, follow these rules:

Any live cell with two or three live neighbors survives.

Any dead cell with three live neighbors becomes a live cell.

All other live cells die in the next generation. Similarly, all other dead cells stay dead.

Repeat these rules for each turn of the game and watch what happens. The fastest and easiest way to understand how the game works is to play it. That is quite easily done; you can play Life online using this emulator. Go ahead—take some time to goof around with it; if you do, you will quickly find that Life is capable of producing some very interesting, pleasing, and even soothing patterns. Here is a “triple pseudo still life.” This pattern will remain in this static state forever when the above rules are applied.

This next pattern is an oscillator—it comes back into the same configuration after a few steps.

Here is a glider—a small pattern that repeats itself every four steps, and “travels” down the playing field as it does so. (Note: this glider pattern is EXTREMELY IMPORTANT. We’ll get to why later.)

Here is what is called an R-pentomino. This small pattern goes completely nuts and takes a very long time to calm down.

Some patterns in Life interact with themselves in intriguing ways. This is Gosper Glider Gun (Bill Gosper, 1970)1—a pattern that continuously “shoots” gliders out of itself.

Now, what happens when two or more of these gliders crash into each other? If you have a moment, create this pattern in the online Life game mentioned above, and watch the result.

In this example, three gliders came together to make what is known as a heavyweight spaceship. This sort of thing is called glider synthesis among Life enthusiasts, and here’s where the game starts to get very elaborate.

Using a setup of guns, spaceships, and other things like reflectors and eaters, you can make complicated patterns that will interact with each other. A gun “shoots” gliders toward a reflector, which “bounces” them toward other gliders, which “bump” into each other and synthesize into still lifes, which, when smashed into by other gliders, turn into spaceships, which smash into gliders to produce guns, which produce gliders that smash into each other to produce rakes, which move across the playing field while emitting still lifes, oscillators, and other spaceships and rakes . . . ad infinitum. For fifty years people have been designing these constructions and sharing them with each other. The first, and one of the most elegant in my mind, is Breeder (1971), by Bill Gosper, which you can view here. But Breeder is just the tip of the iceberg. Enormous constructions of interlocking parts have been built in Life, spaceships such as Mosquito 1 (Nick Gotts, 1998) and Waterbear (Brett Berger / Ivan Fomichev, 2014), and the absolutely immense Gemini (Andrew Wade, 2010), which is made of nearly 850,000 cells and which is so big that my desktop computer can barely run the RLE file that would allow me to watch it in action.

Gemini operates using a mechanism called a “slow salvo”—a stream of gliders, spaced carefully and exactly, that are “read” by the object at the end of their travel path, exactly like a memory tape is read by a computer. There are other ways in which Life can emulate computer systems. From Wikipedia:

If two gliders are shot at a block in a specific position, the block will move closer to the source of the gliders. If three gliders are shot in just the right way, the block will move farther away. This sliding block memory can be used to simulate a counter. It is possible to construct logic gates such as AND, OR, and NOT using gliders. It is possible to build a pattern that acts like a finite-state machine connected to two counters. This has the same computational power as a universal Turing machine, so the Game of Life is theoretically as powerful as any computer with unlimited memory and no time constraints; it is Turing complete. In fact, several different programmable computer architectures have been implemented in the Game of Life, including a pattern that simulates Tetris.

But the ultimate Life creation—and the one that hurts my head just thinking about it—is Metapixel. This creation, designed by Brice Due in 2006, is a construction which can replicate the actions of Conway’s Game of Life on its own. There is a short stream of spaceships that move around the perimeter of this pattern, and if the pattern is repeated across the playing field, the spaceships interact with the edges of the adjacent patterns in such a way that they can turn “on” or “off” other streams of spaceships on the inside of the pattern. For a visualization of this, watch the video at the beginning of this New York Times article. There is some sort of eldritch Lovecraftian horror about this video—a vertigo-inducing, fever-dream quality that arises while watching the view slowly pan out and speed up until you realize that this could go on forever with no limits—one could conceivably build a meta-metapixel using tiled metapixels, and a meta-meta-metapixel using tiled meta-metapixels, and a meta-

Life can be taken very seriously. There is a forum which gets extremely esoteric and arcane; the official wiki is full of jargon like this:

The blinker can function as a transparent catalyst in a certain reaction where it is converted into a traffic light predecessor, which a fishhook (or another catalyst that engages in the same type of catalyzing reaction, such as an eater 2) then converts back to a blinker in the same position. This rephases the blinker, so it can only be used in odd-period oscillators, such as 66P13 and the p47 pre-pulsar shuttle.

That’s not a problem at all, except when the descriptions of Life begin to get bizarrely metaphorical. Remember that anything in Life happens on a cellular level; yet people talk about “spaceships” and “oscillators” is if they are one object. I did, myself, earlier, when I used all of those scare-quote verbs. The individual cells in Life interact with each other according to the rules of the game, but any action in concert or en masse is an illusion. Yet people talk about the game as if it were a microcosm of actual life—the carbon-based kind. The NYT article referenced above contains several of this kind of erroneous take. The worst of them all was by Brian Eno, who says

The second thing Life shows us is something that Darwin hit upon when he was looking at life, the organic version. Complexity arises from simplicity! That is such a revelation; we are used to the idea that anything complex must arise out of something more complex. Human brains design airplanes, not the other way around. Life shows us complex virtual “organisms” arising out of the interaction of a few simple rules—so goodbye “Intelligent Design.”

Um . . . ? I don’t know how an intelligently-designed system is proof against the idea of intelligent design; besides, Life isn’t alive! Some aspects of the game mimic some aspects of the sort of thing that happens in petri dishes, but that is only a metaphor. The colored squares in Life are not alive, no matter what its proponents might seem to be saying—and this is the point where I lose my patience with the whole thing. But— if Life isn’t alive is it at least something else? Is it art?

I’ve been puzzling over a definition of art for as long as I can remember; the questions which opened this essay are the sort of thing that fills my head all the time. The generalized question “what is art?” is too theoretical for this space right now, but my last question, about Conway’s Life specifically, can certainly be answered in the affirmative. Life has all of the features necessary for something to be an art. It is a splendid new medium for artistic endeavor and ought to be approached as such.

What are the requirements for something to be an art? First there has to be a medium. Life’s medium is the colored squares on the grid. Then there has to be a set of tools, techniques, and practices for making the art. In Life, the tools include the array of spaceships and oscillators that have been discovered by Life enthusiasts over the years, as well as the reactions, such as the snark and the eater, which aid in crafting the mechanisms in Life. Its techniques include the slow salvos that power creations such as Demonoid or Gemini; the conduits that transfer information from one part of a pattern to the other; and such things as the honeybit reaction at the heart of Megapixel. These are used by Life practitioners in the same way that renaissance artists used such things as perspective, chiaroscuro, and transparent washes of tinted oils to create their paintings. It has been rumored, but not proven, that Vermeer used an optical device to capture the scenes in his most famous works; there is an analogous scenario in Life: people use software to aid in the discovery and construction of the pieces they make.

Is Life in any way similar to any of the other arts? Like poetry, Life uses a very simple medium. The technics are minimal: poetry is words, Life is black and white squares. Yet in both arts, the fundamental simplicity of the medium allows for undeniably rich and complicated creations.

Another analogy: like sculpture, Life is an art of revealed potentials. It is interesting to note how often Life artists talk about their “discoveries,” instead of their “creations.” Everything in Life is latent in the stark and minimal rules, just like every aspect of a sculpture is there, waiting, in the marble.

Life even has the capacity for stylistic variation—look at the almost representational c/5 Greyship of Hartmut Holzwart versus the clotted mass of goo that is Sir Robin (Adam Goucher, 2018), the curious block-plucking mechanism inherent in 10-Engine Cordership (Dean Hickerson, 1991), or the crablike structures that toss fire between their claws in Ivan Fomichev’s Weekender Distaff (2014). Clearly there is room in Life for individual artistic expression.

Life enthusiasts have themselves realized that what they do is art. The above pattern, a complicated set of intertwined oscillators, was produced in 2020 by Otis Schmakel, and it is titled The Electric Scepter of Spectre, On Surrealistic Pillow. If you watch the pattern develop (which you can do here), it scintillates and pulses with vibrations. Schmakel describes it as “fine art.” It is fascinating to watch how the different oscillators conduct their activities; Schmakel’s creation is only a small selection of all the possible oscillators. But—there are many more kinds of artistries possible in Life.

Oscillators are delightfully intriguing, but they only explore one corner of the medium. There are other patterns that more fully exploit the game’s aesthetic possibilities. Blockstacker (Jason Summers, 1999) releases dozens of gliders and heavyweight spaceships to . . . make a single pile of blocks. The disconnect between the enormous complexity of the mechanism, and the trivial output it produces, borders on the self-referentially comedic. Vacuum Gun (Dietrich Leithner, 1997) slowly pulls an assortment of blocks and beehives into itself before spitting out an endless stream of gliders. This tractor-beam procedure has been employed elsewhere, most notably in Metapixel, where it is used as a clock to cue other parts of the system, but in Vacuum Gun the process is more of a suspense-building one, similar to the tension-and-release found in European classical music, or the beat drop in some EDM songs.

Or what about RacetrackSIX, a collaborative effort from 2016 and the most extravagantly brilliant display of coordination and synchronization I’ve seen so far in my researches2. The pattern is enormous, more than four thousand times as large as Surrealistic Pillow, and is made of several different conduits and mechanisms for modifying and redirecting a single spaceship, which, throughout the course of the pattern’s run, transmogrifies into at least seven other kinds of spaceships, splits into multiple parallel streams (which at one point spell out the phrase “LIFE IS AWESOME”), and bounces like a pinball all over the grid; after more than 355,000 generations, it is finally caught in a trap and turned into an oscillator right before entering the first conduit and beginning the cycle all over again. The whole thing is a giddy, hilarious romp, a tour-de-force display of the full range of spaceship synthesis available in Life.

But if RacetrackSIX is a baroque and florid showcase, Waterbear is spare and focused, evoking the futuristic modernist design aesthetic of 1930s-era trains and turbines. Waterbear is a giant spaceship (even larger than RacetrackSIX), made almost entirely of streams of smaller spaceships interacting with one another. The spaceships cross paths with each other, sometimes without colliding, sometimes crashing and catalyzing the next step in the process. Waterbear is an outstanding demonstration of the highly ordered, precise aesthetic that the larger Life creations exhibit.

A totally different aesthetic is demonstrated by the chaotic “fire” that envelops some Life patterns once they are set in motion. A randomly-generated soup of on and off cells will immediately dissolve into scattered still lifes and oscillators with pockets of froth flickering amongst the ruins. When I asked on Reddit what aspects of Life were the most aesthetically pleasing, there were many people who expressed their enjoyment of this reaction.

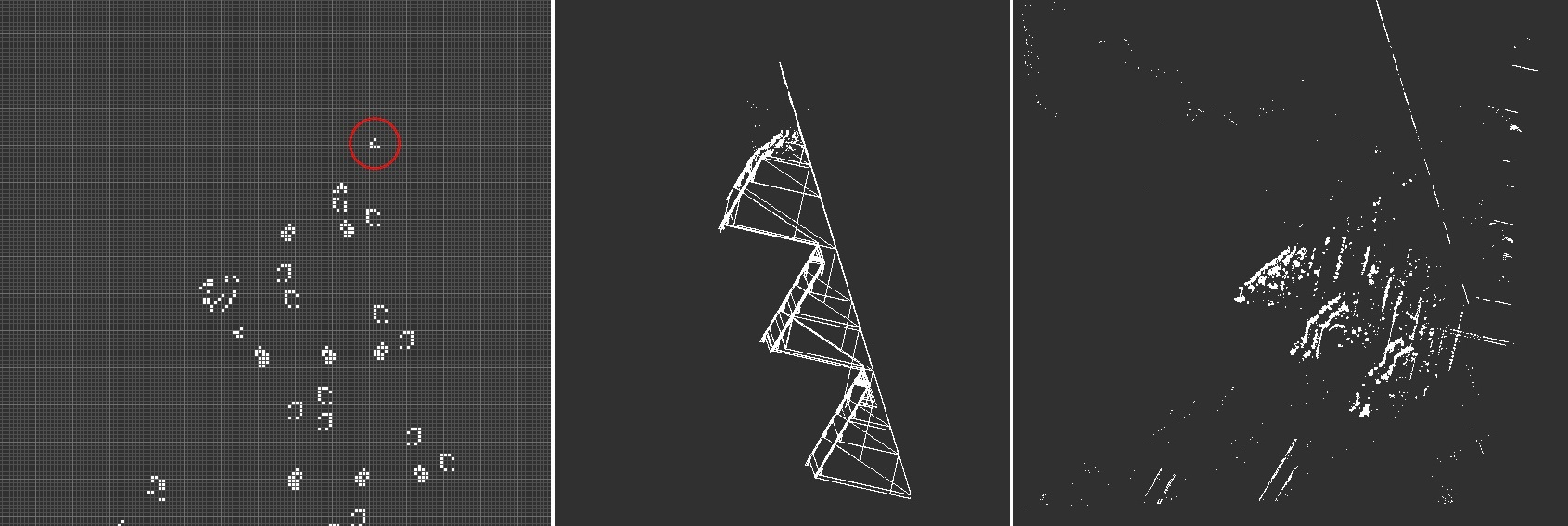

Indeed, there is even an aesthetic quality to destroying a creation in Life. These immense structures are in reality quite fragile. Watch what happens, for instance, when a single extra glider is introduced at the front of Waterbear, as shown in the images at the beginning of this essay; chaos starts happening almost immediately. As the strings of gliders are interrupted some of their intended targets devolve into ash, and some of them spit out additional rogue gliders which initiate a spiral of mayhem that eventually, after more than 70,000 generations, reduces Waterbear to detritus and scattered aimless spaceships. The remains of the Waterbear fuel stack continue to float to the top of the screen, while strands of displaced gliders move away from a smoking heap of ruin in the center—which still indicates traces of Waterbear’s threefold structure but which is only as organized as the scum on a pond.

What does all of this aesthetic expression represent? What does a work in Life signify? Before answering that question I need to clarify what it even means for a work of art to “signify” anything at all. A poem making some observation on existence, or a painting of a landscape, both communicate and signify some aspect of reality. But there are other artworks which do not communicate propositions or representations, yet which still communicate, as Ruskin said, “a seeking for ideal truth” of some kind. There is all sorts of music, from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony to Daft Punk’s “Around the World”, which exist to convey an emotional state, and not much else.

But there is an even deeper level of abstraction. Architecture, as a whole, is an entire artistic discipline which never communicates anything that could be considered representational; buildings say things about power and relationships, but they do not speak propositionally. What about Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs of flowers—the most controversial photographer of the twentieth century produced a set of images that . . . just look like flowers.

What is signified by this painting by Mark Rothko?

This painting doesn’t have any “message” in the sense of propositional content or narrative. This painting exists only to affirm the beauty of color. It is part of the set of art objects that need no justification for their existence; they are just there, reminding us of the pure beauty of the form. That is what I think is going on with Life.

Life signifies the beauty of order. Aesthetic order can indeed be beautiful; there is certainly something sublimely satisfying in seeing all of these spaceships and gliders, colliding on cue, building a larger structure in perfect synchronization. And even in the “disorderly” soups of random cells that dissolve and splash around aimlessly, there is a meta-order to the kinds of reactions that take place. Life, bound by its profoundly simple ruleset, is a perfect method for exploring the implications of order, from the simplest to the most complex level. “Do everything decently and in order”, the Bible says; Life is certainly a means to that end.

I’d like to thank the people of the ConwayLife forums and the r/cellular_automata subreddit, who took the time to discuss Life with me. Your points were very much appreciated!

This essay’s subtitle is a quote from Dostoevsky’s Demons, from the passage describing the bizarre, surrealistic, symbol-laden “poem” written by Stepan Verkhovensky. Dostoevsky’s narrator says that the poem “resembles the second part of Faust”, and in it “a mineral—that is, a completely inanimate object—also gets to sing about something.” And I don’t know a better description of Conway’s Life than that.

For reasons that will become apparent, I will be treating the names of these patterns as the titles of artworks, citing their creators, and referencing the date of their creation.

The link will take you to a forum post with another link to a downloadable RLE file that can be run in Golly. Sorry, that’s the only way I know of to access the pattern—it’s too large to run in LifeViewer like the others.