Artists and agency: assumptions and limits

A friend and I were talking about art which is not entirely fabricated by one person alone, and Damien Hirst’s long-running series of spot paintings came up. As far as I know, Hirst’s method of making a spot painting goes like this: he says to himself “time for another spot painting” and tells his staff to get on it. In Don Thompson’s The $12 Million Stuffed Shark1 the process is described thusly:

The spot paintings are produced by assistants. Hirst tells them what colors to use and where to paint the spots, but he does not touch the final art. Which assistant does the painting apparently matters a lot. Hirst once said that “the best person who ever painted spots for me was Rachel. She’s brilliant, absolutely brilliant. The best spot painting you can have by me is one by Rachel.”

So, who is really the artist—Damien Hirst, or Rachel? A common reaction when confronted with this sort of thing is to say that Hirst is cheating somehow; that he doesn’t really count as the artist of his works. “That’s not how real artists work,” people say. “How can Hirst be considered the artist if he didn’t even paint the picture at all?” This objection reveals deeply-held beliefs about artistic agency, and how art comes into being. But these beliefs are very inconsistently applied. Why do we expect painters to do all the work, when we don’t feel that way about, for example, architects?

Consider this building in my hometown. (I actually live right across the street from it!) The overall form is of several overlapping and combining rectangular elements; obviously, the architect who designed the building chose those shapes. Note the variety of façade materials involved in the building’s surface—again, everyone would agree that these elements were chosen by the architect. These decisions were made deliberately and carefully, for their aesthetic value as well as their suitability to the project.

But look again at the building. Near the center of the image, you’ll see a patch of brickwork, made from several shades of bricks. The arrangement of dark and light bricks interspersed with each other is pleasing to the eye and contributes to the aesthetics of the building. Did the architect have control over even that? Or was it the bricklayer who said “I’ve been laying down light bricks for a while, I think it’s time for another dark brick now,” and thus made choices which affect the final appearance, and therefore the artistic value, of the building? If such is the case, could the bricklayer be said to have “made the artwork” just as much as the architect? And if so, could Hirst’s technicians be the ones who “made” the spot paintings?

We can bring up the same questions when we think about music. It is easy to forget how mediated is our experience of music these days. Yet I doubt anyone would hear OK Computer and then say “Radiohead didn’t make that!” Even a live performance of classical music on acoustic instruments is still mediated by the instruments themselves, which the musicians did not make; the acoustic properties of the concert hall; and even everyone’s being dressed in concert black, which certainly adds something to the aesthetic experience (could this be why the public isn’t invited to rehearsals, since the musicians are still in their street clothes?)

Saying “Radiohead isn’t the artist—they didn’t make those guitars!” is a rather silly thing to say. But some musicians do, in fact, make their own guitars. Yet if that is the case, we say they have mastered two arts. We say they are skilled musicians and also skilled luthiers; there is a division in our minds.

Perhaps there is a continuum of arts, from the most mediated and realized, where we never expect the artist to do the actual work of making the art object; architecture would be in this category. Then we have most kinds of recorded music, which comes to us through amplifiers, mixers, recording studios, streaming services or physical media, and playback devices before it gets to our ears. Then I suppose sculpting in bronze would come next; technicians must be employed to cast bronzes such as Rodin’s The Thinker or Cellini’s Perseus—the artist doesn’t do that on their own. Then our continuum proceeds through things like glassblowing, quilting, and ceramics, till we expect the artist and the producer of the work to be the same person. Finally we arrive at painting, the art where we have definite expectations and assumptions about the artist’s role as the sole actor in the production process.

Okay, what about poetry? Surely here is an art where the creator and producer of the work are always, indisputably, the exact same person. Poetry can be composed in one’s head, memorized, and pondered in the solipsistic silence of one’s mind—there isn’t a physical object at all. Or is there??

When was the last time you heard a poet recite their own work? Recordings don’t count—you would run into the same problems we discussed under music. I imagine there are people reading this who could conceivably have heard Maya Angelou or Billy Collins recite their pieces in person. But have you ever heard T. S. Eliot? Jonathan Swift? Chaucer? Sappho?

Turns out, poetry is just as mediated as music—whoever designed the books that poems are found in had enormous control over how that poem is perceived. Of course, nowadays, poets can get involved with the choice of font, the quality of the paper, the front cover illustration—but poets like Chaucer or Sappho don’t get to be part of the process when their works get reprinted.

“The art in poetry is the words, not the font or the kind of paper,” I hear someone saying. And yes, they are right. Similarly, the art in music is the sounds.2 But with the plastic arts, things get more complicated. The art in flower arranging is the arranging; the flowers were made by God, not the artist who created the arrangement—yet surely we could all agree that the flowers themselves play a very important part in the final piece. I’ve never heard of a quilter who wove their own cloth, although it is certainly possible; most quilters use the patterns and textures of someone else’s fabric in their own finished pieces, and are not expected to acknowledge the creators of the fabric as collaborators. In architecture, the art object is . . . the whole building. We are right back where we started, wondering who chose where to put the dark bricks.

The art in painting is the actual painting itself; that is why prints of Mona Lisa can be bought in the Louvre gift shop, but the real thing is kept behind six-inch-thick glass. Leonardo is revered as the artist who created Mona Lisa, not any assistants who might possibly have stretched the canvas or mixed the paint. Velázquez is the artist who created The Maids of Honor, even though it was king Philip IV who painted the red cross of the Order of Santiago onto the painter’s chest after Velázquez died. So does this mean Rachel is the artist who created the spot paintings, even though Damien Hirst gets to put his name on them and sell them for millions of dollars?

“In all arts, the art is in the decision-making process, not in the creation of the final product,” explains an auction-house employee. And I agree with that. It is notable that the Bible seems to speak about artists in the same way; in 2 Chronicles 3 and 4, it is king Solomon who is described as having built the temple in Jerusalem, and in Exodus 36-39, Bezalel is the one who makes the furnishings for the tabernacle. But Bezalel is also said to have worked with a cadre of “gifted artisans.” Is the difference between degrees of artistic agency—the difference between Hirst and Rachel—a difference between art and craft? If so, what is that difference?

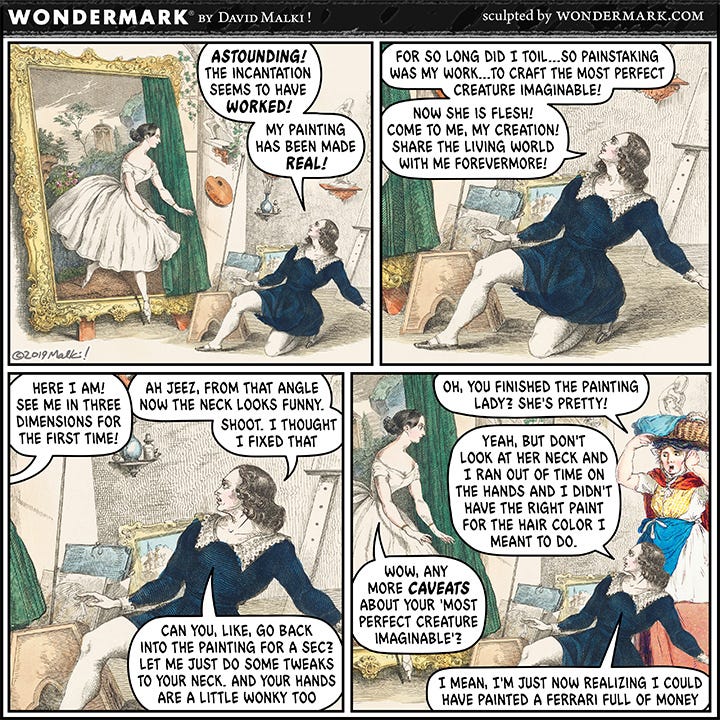

OK now for some Wondermark.

What is this, like, the fourth or fifth time I’ve mentioned this book!? It’s seriously one of the most powerfully disturbing books about art that I’ve ever read. Maybe I should write a review or something.

At least, such is the case for rock music; this is the point very cogently argued in Rhythym and Noise by Theodore Gracyk. For classical music, the art might be in the composition, and the music might exist, as an art object, even if it is never heard at all.