From the front lines of the NFT vs. furry war

Well! It’s been a while since the art world had a good old-fashioned ideological battle. I’m not talking about the predictable outrage that happens when someone decides to use a flask of urine to filter the light in a photograph of a crucifix, or when someone pays a dozen million dollars for a piece of taxidermy. I’m talking about the kind of fight that causes different parties and factions of the art world to come out of the woodwork (or the twitterverse) and scream at each other in deliberately provocative ways.

If you’ve been online for any amount of time this past year, you’ve undoubtedly heard talk about NFTs. The abbreviation stands for non-fungible token, and refers to a unique identifier associated with a digital asset, using the same blockchain technology that powers cryptocurrencies like ethereum and bitcoin. Unlike cryptocurrencies, where every coin is interchangeable with every other, a non-fungible token is unique, and cannot be switched out with another one, meaning different NFTs can have differing cash values. How it all works is beyond the scope of this essay, but for our purposes, Mitchell Clark explains it pretty well:

NFTs are designed to give you something that can’t be copied: ownership of the work (though the artist can still retain the copyright and reproduction rights, just like with physical artwork). To put it in terms of physical art collecting: anyone can buy a Monet print. But only one person can own the original.

NFTs have been taking the high-end collectible art market by storm this past year. Celebrities of every type, from Grimes to Jimmy Fallon to all sorts of sports figures, are either buying NFTs or making their own. But what, exactly, are people acquiring when they purchase an NFT?

In the words of Harvard legal scholar Rebecca Tushnet, “The value is the ability to say that you own the NFT. Like blockchain currency, it is worth whatever humanity collectively or individually decides it’s worth. It is a melding of Oscar Wilde and Andy Warhol, art for art’s sake and commerce for commerce’s sake.” You know what? Whatever. Rich people have always been consuming conspicuously, proving to the rest of us how rich they are by buying things that the culture considers to be luxurious or classy or high-status. In the 18th century in England, the one percent would spend piles on elaborate formal gardens, even going so far as to build little grottoes in them and hire old men to sit in them, larping as hermits. For the past forty or so years, the rich have been buying avant-garde paintings and sculptures like crazy, especially ones that could be immediately recognizable from across a crowded cocktail party— “is that a real Warhol!?” And now, the big thing is non-fungible tokens.

For the purposes of class signaling and conspicuous consumption, it is extremely important that these NFTs be recognized as NFTs. Which is why, if you go to an NFT marketplace like OpenSea, you will notice that the top sellers, the ones that command the highest prices, conform to a basic NFT template—anthropomorphized animals, facing right—and within this basic template, each branded collection is very identifiable. There are ten thousand bored apes; 7,777 crypto bulls; 10,080 lazy lions. There are, of course, numerous exceptions to this rule, some of which get sold for enormous heaps of money. Really, the NFT market is just the same as any other speculative art market, and the high-dollar art is usually the stuff that is immediately recognizable, whether it is because it’s part of a branded collection (like a bored ape) or because it’s well-known in some other context (an NFT of the original Disaster Girl meme sold for half a million dollars last April).

Art being used purely as a status symbol is the unfortunate status quo; that use probably won’t go away.1 Digital art has been around for a while, but couldn’t really take off financially until the advent of blockchain technology made it possible to verify ownership. There was a sudden increase in interest around NFTs as soon as they began to be created—driven, no doubt, by the general aura of fancy, cutting-edge, on-trendiness that the entire cryptocurrency / blockchain ecosystem represents. Some digital artists like Beeple, who make one-off NFTs not tied to a collection like Lazy Lions, have been able to achieve prices in the millions of dollars for their works; Beeple’s NFT of Everydays: The First 5000 Days is currently one of the most expensive artworks by a living artist, putting Beeple in the company of such titans as Jeff Koons and Jasper Johns.

However, as soon as the wealthy owners of NFT images started using them as avatars on social media, the backlash began. People started to ridicule the whole thing, taunting the NFT owners by right-clicking and saving the images, claiming that doing so invalidated the entire premise of NFT ownership. This argument went back and forth, with neither side really caring about what the other was saying; or as Matthew Gault and Jordan Pearson wrote in Vice last fall,

To right-clickers, the blockchain ledger where their receipt resides is a comforting technological myth that NFT owners point to to legitimate their claims of ownership of a JPEG. It’s a kind of slacktivism, a way to address the problem without risking anything. Right-clicking a JPEG, saving it, and displaying it back to the NFT owner is a way to point out the Emperor has no clothes. Meanwhile, the NFT fans make millions off their naked Emperor. Round and round.

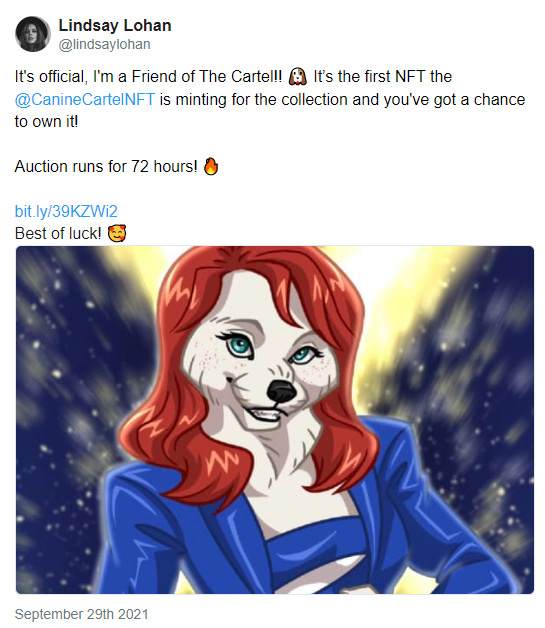

Then, this happened.

This publicity move / celebrity endorsement by Lindsey Lohan (yes, that Lindsey Lohan) was interpreted by members of the very-online, very-marginalized furry community as a misguided and disrespectful act of cultural appropriation. For starts, they criticized the image’s quality; it is, apparently, a very poor example of furry-themed art. Rolling Stone’s EJ Dickson reports:

“Flat D, perhaps even a D-,” says Colin Spacetwinks, a writer in the furry community. “It reminds me in a way of frequently insecure straight artists rendering furries: [diminish] and reduce furry traits so as to not ‘commit’ to what you’re doing. Ears covered, why? Feels like it’s avoiding animal traits on purpose.”

But it goes farther than that. Furry artists see all of the animal NFT social media avatars as a tasteless trend among wealthy crypto investors who are appropriating an aspect of their own subculture—the personalized fursona—that they take great pride in. As furry artist Reyn Goldfur pointed out, “I can give you the names of so many furry artists who will draw you SO MUCH BETTER QUALITY art than this, of ANY design you can imagine/describe, for FAR less than that for what is essentially just a headshot with a quick background.” Furry artists put a great deal of care, thought, and personalization into the pieces they create for members of their community; Lohan’s fursona doesn’t seem to do any of that.

The right-clickers, led by the furries, exhibit a fundamental misunderstanding of what an NFT really is. It does not convey ownership, or exclusive rights, to an image; as Vincent Van Dough, creator of Right Click Save This (screenshotted above), explains, “NFTs are just a receipt they say, but that receipt lets us verify the creator and come to consensus on the original version no matter how many times it’s reproduced or remixed.” Having such a way to verify originality would be very helpful in the art world; instances of high-profile scandals involving faked masterpieces (such as what happened with paintings by Vermeer and Monet) would practically disappear. And when artists working in digital media create NFTs of their art, they can easily enjoy a financial reward that can be much greater than if they were working in a traditional market, thereby enabling artists to support themselves much more effectively, and empowering them to focus more on developing their art—a virtuous circle indeed.

But when an artist begins to interfere with the symbols, styles, techniques, and overall aesthetic of a marginalized group’s perceived cultural identity, people can get very upset, and they can start to vocalize their anger and their sense of being exploited. Major corporations don’t want that kind of backlash; when challenged about their use of cultural symbols from marginalized peoples, the corporations almost always take down the offending images. Such is the case of Mutual of Omaha, which recently changed their logo from a Native American chief with headdress to a lion (not a lazy one, I’m sure the company stockholders hope).

Artists, on the other hand, have a long history of being provocative and even offensive for the purposes of making a point. This kind of behavior ought to be expected from artists, but is there a line that must not be crossed? What amount of provocation is simply too much? At what point does an artist’s desire to be transgressive for the sake of argument need to give way to a prior obligation to show respect and kindness? These are questions that everyone in the art world—from the artists themselves, to collectors, gallery owners, museum curators, and the art-loving public, must ask.

If you want to read more about this happening from a crypto-enthusiast angle, I recommend this short essay by Gian Ferrer (it’s where I got the Vincent Van Dough quote above).

An invaluable source of as-it-unfolds analysis on this topic has been Ryan Broderick’s Garbage Day newsletter. This piece in particular is excellent in laying out the terms of the conflict, and where it might go next (spoiler: Broderick is pessimistic about the value of crypto in general, and especially what it might do to any future conception of what the internet will evolve into).

For an explanation of how art is used as a status symbol, and the economics of such a use, read Don Thompson’s The $12 Million Stuffed Shark. This is the second time I’ve referenced this amazing and rather disturbing book; I promise that one of these days I will write a full review of it.

The world of NFTs has been such a whirlwind so thank you for sharing both sides of the arguments in a clear and concise way!