Blankets (Craig Thompson, 2003)

A defect in the shepherding: Part one

Note: the temptation to spend this entire review grandstanding is very strong. My mental dialogue with Blankets takes the form of thoughts like “See! This is why parents shouldn’t be emotionally distant from their children! This is why religious leaders should have more humility when questions are asked of them! This is why teenagers should cultivate a sense of purpose rather than drifting awkwardly around!” There is much unpleasantness in the relational situations Craig encounters in the novel, but treating Blankets like an opportunity for quote-tweeting is not charitable at all. The events recorded in Blankets are presented as the real experiences of the book’s author, Craig Thompson. And the lived experience of any person, however much we might disapprove of what caused it, is worthy of our sympathy and understanding.

Once a genre devoted to bombastic action and over-the-top unbelievability, comics—um, excuse me, graphic novels—have now pivoted to being the ideal platform for tales of personal reflection, loneliness, and isolation. This trend started in 1978 with Will Eisner’s A Contract with God and has only continued through the works of such artists as Chris Ware (Jimmy Corrigan, Rusty Brown), Kristen Radtke (Imagine Wanting Only This, Seek You), and Alison Bechdel (Fun Home). Solidly within this tradition is Craig Thompson’s autobiographical novel Blankets, which propelled him to stardom in the comics world and won him just about every award that a graphic novel can get. It also got banned from at least one public library, ostensibly because of the book’s nudity but perhaps really because it wasn’t considered the sort of book that kids should be wrapping their head around on their own. This is a dark, heavy, sad book, despite its numerous passages of warmth and wonder. My closest referent is that it’s a Catcher in the Rye with pictures instead of words, (almost) no swearing, and a focus on faith instead of school.

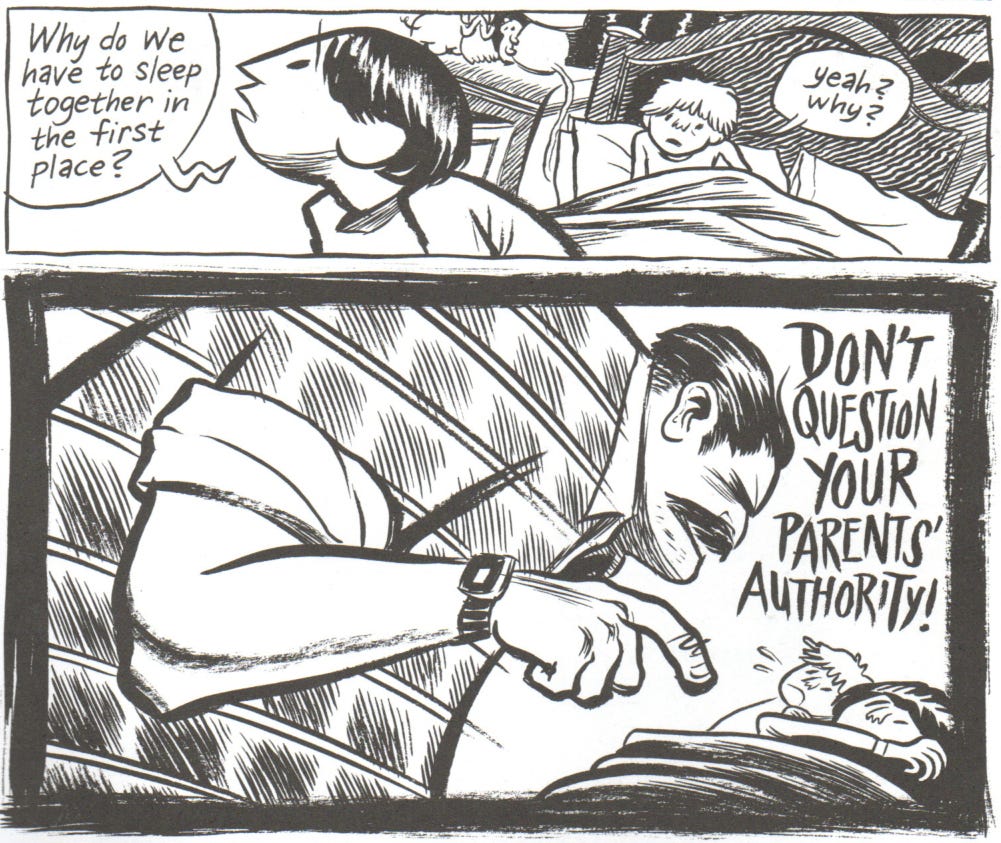

In powerfully expressionistic brush-and-ink drawings,1 Thompson evokes his own experiences growing up with his brother in a strictly religious, authoritarian home; his isolation and ostracism from his schoolmates; his uneasy relationship with the religion of his youth, and his eventual abandonment of the Christian faith. The story focuses on the winter of Craig’s senior year during which he meets a kindred spirit—Raina, who becomes his first love. The story contains many flashbacks to Craig’s childhood, focusing on the escapades he and his younger brother shared as they were growing up. Aside from these times spent playing with Phil, Craig’s childhood memories are unremittingly bleak and nasty, full of bullies at school, angry parents, and misunderstanding. The end of the story almost seems inevitable: Craig has always longed to be free, to express himself, to follow his own path, and in the end he is totally unmoored from everything. Is this good? Thompson never says so, explicitly.

The tension between Craig, Raina, and their familial expectations is the engine which drives the action in this book. Craig can’t get away from his emotionally distant yet domineering father, and the relational wasteland of his school; Raina can’t escape the childcare responsibilities forced upon her by her neglectful parents and sister. They both want to get out from under the burden of relationships gone wrong. In each other they find that escape, and the freedom to just be, without obligations, or without having people worry about them all the time. The passages in the book where they silently walk through snowy forests or drive around town aimlessly are simultaneously the most touching, and the saddest, parts of their story—it’s sad that they’ve never had this kind of rapport with anyone else in their lives so far. Cooped up in their little worlds of familial obligations, Craig and Raina have missed so much. Now they’ve finally reached the age where they can feel the walls around them and are just now pushing back in earnest.

What does Craig really want, anyway? what is his reason for pursuing a relationship with Raina? He is initially attracted to her simply because she is different from the people he knows back home. But Craig’s friendship with Raina, and their budding romance, goes nowhere. Raina refuses to usher Craig into any kind of heightened awareness of his own self; soon after he gets back home after staying with her for two weeks, she tells him that she’s not ready for a romantic relationship. Later that spring, they break off their friendship entirely. Really, they were only using each other for emotional release. After they achieve that release, they don’t need each other anymore. And although they might have felt some sort of affinity, they weren’t even concerned about the same things: without realizing it, Craig was looking for answers to life’s big questions, while Raina was just looking for escape. All either of them really wants is just to grow up—to be the masters of their own fates, to enter into the full franchise of adulthood, where the well-meaning concern of parents and other authority figures isn’t something they are obligated to take into account.

It is telling that when Raina expresses strong doubts regarding the teachings of Christianity, Craig doesn’t try to contradict her. it’s almost as if he shared those doubts deep down and was simply unwilling to express them / was waiting for someone else to express them instead. It’s no surprise, then, that Craig abandons his faith in the end. His story bears similarities to that of Stephen Dedalus in Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, who thought that extreme religious devotion would somehow jumpstart the fading embers of a faith he never really had. As soon as Stephen and Craig start questioning the assumptions of their faith, it falls apart.

Blankets is a coming-of-age story. As such, Craig spends most of the story floating around in his own immaturity, with no plans or goals other than a vague inclination to go to art school. He has no idea how to get what he wants, is unable to maintain a relationship with his brother, and can’t really articulate to Raina why he loves her. All of this feels very true-to-life to me, and I can relate; I was in a similar place when I was Craig’s age. At eighteen I also had no serious ambitions for anything, wasn’t really paying attention to my family, and had done and said incredibly cheesy, cringe-inducing things to girls. That’s how it goes for people, like me and Craig, who are drifting through life not really knowing what they want.

Craig reminds me of a multiverse version of myself. There are several points in his story where I have to pause and think “that could have been me, if such-and-such a detail had been different in my life.” Like Craig, I was raised in an evangelical Christian family, but my father was not a stern and authoritarian figure—he was more like a coach. Although the churches I went to were very similar to the church Craig’s family attends, religion itself, in my home, was a very private thing. I never remember my parents dogmatically projecting their worldview on me or any of my siblings the way Craig’s dad does. I was socially awkward as a kid, and I didn’t feel close to or try to get along with my siblings, but I was never bullied or harassed by classmates (because I was homeschooled). That whole side of Craig’s lived experience is absent in my life.

Also, I never remember being puzzled by the kind of religious questions that occupy Craig’s mind. For me, the conceptualization of religion that my parents and social circle passed down to me was simply the way the world worked, and I just . . . accepted it all, without really thinking about it. The most important difference between my upbringing and Craig’s is how supportive of my own artistic pursuits were my parents. There was never a tension between my own interests and how I was expected to use my time. One of the most painful scenes, for me, in Blankets is when Craig’s Sunday school teacher tells him that he can’t praise God with his drawings. That idea would have been incomprehensible to me when I was Craig’s age; no one ever told me anything like that.

Craig abandoned his Christianity; I did not. Here is where our multiverses diverge the sharpest—what would have happened if his parents had just reacted differently, or if the leaders at his church had been humbler and more nuanced with their answers? Would Craig have abandoned his faith? This is why I think Blankets is a tragedy. I believe that Christianity does indeed have the answers to the difficult questions that Craig was asking, and I’m sad there was a defect in his shepherding—that he didn’t get the answers that he needed.

Perhaps, then, my reading of Blankets is as a cautionary tale directed to parents and teachers. What we parents do, what we say, how we act, has incalculable effect on our children’s eventual makeup. We must be careful.

One of the most profoundly tragic passages in all of literature happens right at the beginning of J. M. Barrie’s Peter and Wendy.

All children, except one, grow up. They soon know that they will grow up, and the way Wendy knew was this. One day when she was two years old she was playing in a garden, and she plucked another flower and ran with it to her mother. I suppose she must have looked rather delightful, for Mrs. Darling put her hand on her heart and cried, “Oh, why can’t you remain like this forever!” This was all that passed between them on the subject, but henceforth Wendy knew that she must grow up. You always know after you are two. Two is the beginning of the end.

Think about that for a moment: The beginning of the end. The end of what? If childhood is an age of innocence, it is also an age of terrible sadness and disappointment. Coming-of-age tales are records of the end of those two ages, and if Barrie is right and two is the beginning of the end, then eighteen is the end of the end. Craig comes into a fuller realization of who he is; previously, as a kid, there was so much of the world that he didn’t understand—but as an adult, setting out on his own path, he has grasped the true meaning of what he sees around him. He remembers a time when he and his brother discovered a cave in a nearby field; every time they visited the cave, it got smaller, and eventually it wasn’t there at all. This passage is tied symbolically, in Blankets, with Plato’s famous analogy of the cave, and with Craig’s gradual rejection of his Christianity.2 The process of maturity, of coming-of-age, is equated with a process of disenchantment which is also a process of enlightenment. What is all this—a net gain, or a net loss?

Craig loses so much at the end of Blankets. He loses his religion, but he also loses Raina; it is difficult to tell which loss means more to him—or if either loss means anything to him. During the course of the novel, Craig had lived in a world where his support structures are all actively failing him in some way or another—his father does not provide encouragement or love; his pastor is unable to answer his questions about the faith; his school is merely a place of torment and bullying; even his girlfriend withholds the emotional support she gave at first. But at the end, Craig finds himself without any support structures at all, broken or otherwise. Returning home for the Christmas holiday, he knows that his parents won’t be able to handle the truth about his leaving the faith, so he doesn’t tell them. But even more disheartening is that his family won’t even go outside and take a walk in the freshly fallen snow with him.

And although it doesn’t seem to bother him, I can’t help but feel that this lack of support—this total aloneness—is the most tragic thing of all.

So expressionistic, in fact, that I have trouble believing them to be true representations of what happened in Craig Thompson’s life. The precisely rendered scenes in Fun Home give me reason to think that Alison Bechdel was telling the truth in her story; in Blankets, I do not have that assurance.

I must admit that the whole “Plato’s cave / Craig’s cave” passage doesn’t seem, in my estimation, to fit with the rest of the book. There is no other part of the book which is as overtly metaphorical and symbolic. It sticks out obtrusively in an otherwise very impeccably structured story.