Why is it that the most vocal critics of Christian films and filmmakers are . . . Christians? You would think that the fans would be cheering most loudly for the home team, but it seems that it’s practically impossible to get a broad swath of the Christian critics to endorse any particular film by a Christian filmmaker or any film which considers the Bible or Christian theology. What is going on here? Why are Christian films such a battle zone among Christian critics?

In my admittedly biased and prejudiced opinion, a big part of the answer to that question lies with the attitude many (but not all) Christian critics have towards the art of filmmaking. Before I discuss that, though, I would like to mention a few of the different views that I’ve encountered when talking with my fellow Christians about movies. The definition of what counts as a “Christian” film is extremely vague and varies from person to person. Christians themselves are not a monolithic group, and different Christians want different things from the films which are made as part of the Christian religious experience and expression. When these different views and expectations collide, there can be trouble. I know of four different views, among Christians, of what a “Christian” film should be—let’s take a look at them.

Some people consider a film “Christian” if it is about Biblical subjects: films such as The Ten Commandments, The Passion of The Christ, or Darren Aronofsky’s Noah. The average Christian movie watcher is probably well-informed about the subjects these films seek to represent. Problems occur when these films don’t adhere to the stories as they are presented in the Bible. Despite it being routine practice for filmmakers to change a story to fit the demands of the art of film, some Christians don’t like that—for them, it is important to precisely duplicate the Biblical story. Fair or not, this attitude towards the telling of stories which Christians feel are “theirs” bears quite a lot of similarity to the feelings of marginalized minorities who chafe at what they perceive to be disrespectful cultural appropriation. The degree to which you sympathize with people who are concerned about cultural appropriation is probably the degree to which you will sympathize with Christian filmgoers who demand faithfulness to the Biblical narrative in the films they watch.

A different faction of critics simply wants films which have Christian themes. They want to see their faith discussed in films and they don’t want the Christian religion to be erased from the cultural conversation. As long as there are films being made which consider the Christian faith with respect, these Christian viewers are happy. The majority of these kinds of films are made by Christians, for Christians. There is a whole spectrum of quality in these movies, from the rather well-made to the absolutely atrocious. There is also a spectrum of how much these movies will pander to the audience and offer fan service versus how much they will challenge Christians to examine their faith in fresh and difficult ways. This latter approach to films about Christianity is often deployed by established filmmakers from the secular world: Robert Duvall’s The Apostle is an example of a film in this category which asks some tough questions about the faith; so are M. Night Shyamalan’s Signs and Milos Forman’s Amadeus. But despite the presence of serious and respectful consideration of the faith in these films, I doubt the majority of Christians would ever call them “Christian films.”

There is a third faction: the critics who don’t want specifically “Cristian” films; they simply want films which inhabit a Christian moral universe—the Lord of the Rings movies are good examples—in which the good guys win, evil characters do not go unpunished, people suffer for their sinful mistakes, etc. The people in this faction are displeased when a filmmaker creates a movie that does not reflect Christian moral truths (for instance something like Pulp Fiction); they don’t like it, whether or not it has artistic merit. For these people, the art of a film is not as important as its message; form follows function for them.

All of these factions have this in common: they think of films as tools for communicating a message—ideally a Christian message. Is this fair, though? Earlier I mentioned that a big part of the disagreements about films among Christians lies in their attitude towards the art of film; and I honestly believe that films are a much more intricate art than many Christians realize. Films tell stories, but they often do so in extremely subtle ways; often it takes a lot of thought before a person can “get” a particular film—and that isn’t bad. I think films are an excellent example of what C. S. Lewis was talking about in Experiment in Criticism: “The first demand any work of art makes upon us is surrender. Look. Listen. Receive. Get yourself out of the way. There is no good asking first whether the work before you deserves such a surrender, for until you have surrendered you cannot possibly find out.” There is a necessary humility that must be assumed before the tough, complicated art will reveal its treasures.

And films are, quite often, these tough and complicated works of art. So much goes into a film: writing, set design, editing, soundtrack—even casting choices and costume design can play a profound role in communicating the artist’s vision. I truly believe that there are many Christian movie watchers who are unwilling to let films be as complicated as they could be, and that’s sad—we Christians are not getting ourselves out of the way, unwittingly creating amongst ourselves an attitude of superiority to the art of filmmaking which is hurting our ability to appreciate the art form.

But this attitude is not universal among Christians. The fourth critical faction I want to describe is made of those Christians who do, in fact, want to engage seriously and deeply with the art of films; these people simply want Christian filmmakers to produce quality work, and they don’t really care if the film presents an explicitly Christian message—in fact, they might get upset if the film “tells” more than it “shows.” For these people, the film doesn’t matter as much as the people who made it; their desire is to see more Christians producing work of the highest artistic quality, whatever it may be.

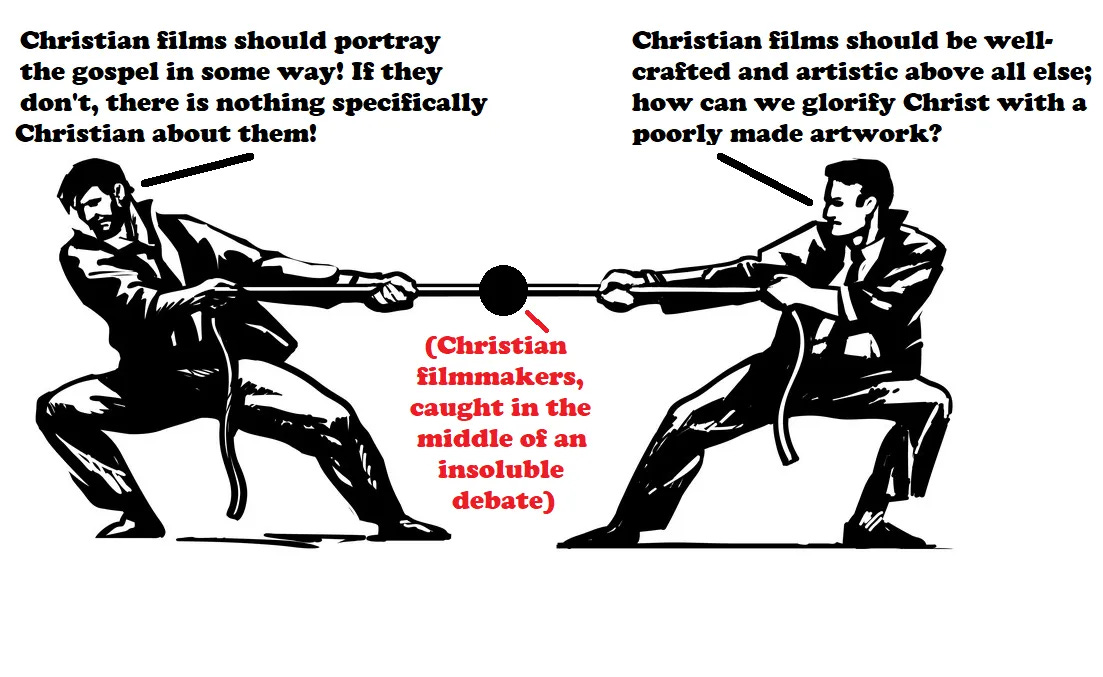

There are most certainly gradients and nuances between these four factions, and any individual Christian film critic might inhabit several of these factions at once; they might even consider different films, or the same film, from any or all of the four perspectives we’ve discussed. Their views have the right to be exceedingly nuanced. All of this means that the definition of “Christian film” cannot be agreed upon—and hence, the “right way” to make a Christian film is a matter of debate.

In a recent essay called “Christian Filmmaking Needs a Shift,” Cap Stewart writes about how he is encouraged by the contemporary landscape of filmmaking by Christians: “The Christian film industry generally appears to be slowly moving in the right direction, nearing the goalposts of high-quality art with every step.” But Stewart’s “high-quality art” criterion is, as we’ve seen, only one of several directions in which Christians want films to go; for some people, the emphasis on art (which by necessity coincides with a de-emphasis on didacticism) is the wrong direction. I have had Christians tell me that a film was good because it had “a redemptive message”; they didn’t consider the other aspects of the cinematographic art at all. Is this why Christians so often have a hard time making a movie which is accepted as “good” by the rest of culture, why the cliché of the poorly-written, poorly-acted, poorly-produced Christian movie rings so disappointingly true so often?

Good storytelling relies on, as Zef Foster says (in an essay with the provocative title “Time to let the Christian Movie Die”), “show[ing] virtue through themes and characters, rather than through overt signaling.” Cap Stewart would agree—in his above-mentioned essay he writes about how Christian filmmakers “take a visual medium like film, which is designed to show rather than tell, and craft a story that tells rather than shows.” Perhaps Christian filmmakers have mistaken the content for the form, and in their zeal to craft a good moral, they have forgotten the entire rest of the filmmaker’s art.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Christians could be making films full of well-stated yet artistically nuanced portrayals of the truth of their faith. Think of Roy Batty’s nail-pierced hand reaching out to save the life of the undeserving Rick Deckard in Blade Runner, or the nearly identical Christ-figure of Captain Sharp in Moonrise Kingdom, reaching (from a church steeple!) to save Sam and Suzy from certain death. Think of how Alma Elson’s struggles with Reynolds Woodcock in Phantom Thread illustrate the truth that God’s plans for us are better than our own. Think of the powerful portrayal of the responsibility to keep and steward the Earth presented in WALL-E. How about the depiction of a loving and stable marriage of two people who are committed to each other “for better or for worse,” weathering trials and remaining steadfast, in While We’re Young? None of these movies were made as explicitly Christian movies; I don’t even know if any of their makers are Christians—but their works offer intriguing portrayals of Christian doctrine, and Christian filmmakers can learn from their storytelling methods.

When I talked about these ideas on the internet, one person told me this very wise aphorism: Films are not either Christian or non-Christian; only people can be. There is a great amount of truth in that statement, and perhaps the whole struggle over “Christian films” ought to be abandoned for more productive battles. But I doubt that will happen. Christian critics will keep going to the movies, and they will keep evaluating what they see through the lens of faith: and this is as it should be. Christians will also keep making films—hopefully, to the best of their ability and with respect for the art form. It does seem like Christian films have come a long way but at the same time that they have a long way to go. Pulled between the twin poles of “gospel message” and “art,” the idea of “Christian film” is indeed in a difficult situation.