Civic sculpture in Omaha

The ongoing brouhaha over Seward Johnson’s Embracing Peace sculptures (they infringe on copyrights! They glorify sexual assault! They are simply too ugly to count as good art!) has found its way to dear old Omaha; one of the gargantuan things is on display in Memorial Park until November, as you can see in the image above. I don’t know—my first reaction is that it is simply too big and entirely out of scale with the surroundings. In fact, it’s so big that if you go up to it, you can barely see it. The park is celebrating its 75th anniversary this year, and I wonder: why Embracing Peace, specifically, in Omaha of all places? And then I wonder: what counts as appropriate civic / public sculpture, anyway?

The first time I was exposed to civic sculpture in Omaha was back in 2001, when the city commissioned and displayed a series of sculptures called simply “J. Doe.” The series was made of androgynous humanoid figures which were given to various local artists to decorate, modify, and otherwise make their own; then, they were placed all over town. This would have been when I was sixteen or so. There were about a hundred of them; it was great fun to be able to drive or walk around the city, come upon one of these J. Does suddenly, and admire the artistic choices which made the generic figure into something unique. They were on display publicly for a while, and then the collection was sold piece by piece; some of them were kept in their original locations for a time, but I have no idea where they are now. That’s too bad; it would be cool if they were still around.1

Apparently there are several similar sets of civic sculptures in the Midwest; I know of similar art projects in Chicago and Kansas City. In Nebraska, there are related projects in Lincoln (heart-themed), Auburn (honeybees), and Nebraska City (trees)—there might be more, but these are the ones I’ve personally encountered. But of course the question must be asked, “Why this humanoid figure?” In 2007, Omaha again undertook a citywide public art project—this time the blanks given to are artists were large “O!” symbols. The process for these sculptures was the same as that of the J. Does, only this time, to me at least, there was more connection to the community—I’ve seen people in many other places besides Omaha, but “O” is the city’s initial. Again, I am not aware of the fate of the “O!” sculptures, except for one—in Memorial Park (coincidentally at the foot of the hill upon which Embracing Peace stands).

Remembering these sets of sculptures leads me on a reverie about the other kinds of art which can be seen in public places throughout Omaha. My city is rich in this sort of thing. I’m not talking about the large sculptures used to decorate office campuses; these, while able to be seen by the public, are still privately-owned works of art which reflect the owner’s idiosyncrasies more than anything. What I want to discuss is the kind of art which can be found in places like city parks, the campuses of universities, and other places which are part of the fabric of shared communal space necessary for a city to have a vibrant, outward-facing public life. This blog has already featured Leslie Iwai’s excellent sculpture Sounding Stones which is installed in Elmwood Park; a sculpture very similar in purpose is on the campus of the Nebraska Medical center. It is by Jun Kaneko; here’s a picture of part of it (there are more ceramic columns out of the frame to the left).

The sculpture is especially complex and can’t fully be appreciated in an elevation view like this; you really must see it in person to get an appreciation of its form. A plaque nearby explains the significance of the forms and how they are arranged, tying them to the Shakkei principles of garden design from Kaneko’s native Japan.

Another public sculpture, and one rather more legible and readable than Kaneko’s ceramic pillars, is located at the Annette and Richard Bloch Cancer Survivor’s Park. The sculpture here is meant to describe the fight against cancer. In the image below you can see (to the left) some figures with worried and stern expressions about to enter a twisted metal maze; some figures have already been through the maze and their faces are full of joy. The large wooden arches and the set of pillars in the background of the picture display inspirational quotes all related to the struggle against cancer. It’s a very good assemblage of pieces; contemplative and inviting a lingering appreciation, it has meaning for many kinds of people—cancer survivors, those going through treatment, and even someone like me who has never experienced cancer but who is aware of the impact it could have in my life.

These sculptures—Iwai’s Sounding Stones, Kaneko’s Origins, and the Cancer Survivor’s Park—are all large, imposing, and make their presence felt in their respective locations, but the truth is that they each could have been situated in any city. Another category of public sculpture in Omaha is that of pieces which seek to reflect on the specificity and history of their location. These come in two kinds: pieces designed as “decoration” for quasi-public institutions like Omaha’s CHI Health Center2 or Children’s Hospital, and pieces with a more didactic or explanatory function. I’ll showcase two relatively smaller versions of the latter kind before discussing what I consider the best example of civic sculpture to be found in Omaha.

Below is an image of The Road to Omaha. Every June, Omaha hosts the NCAA Men’s College World Series, and it’s a major event: the area around the city’s baseball field becomes clotted with crowds of pedestrians strolling around, visiting the restaurants, bars, and sports shops in the area, or going in and out of the ball game—I should know, because it’s right on my way home from work and I have to be careful about the crowds. The College World Series is part of Omaha’s identity, and Lajba’s sculpture serves to remind visitors of the historical aspect of that identity. The statue was given by the College World Series to the city in commemoration of fifty years of hosting the tournament. There is also a sentimental angle; for the first several years of its existence, The Road to Omaha was positioned at Rosenblatt Stadium, which has since been torn down and which was, and still is, a beloved part of Omaha’s cultural memory.

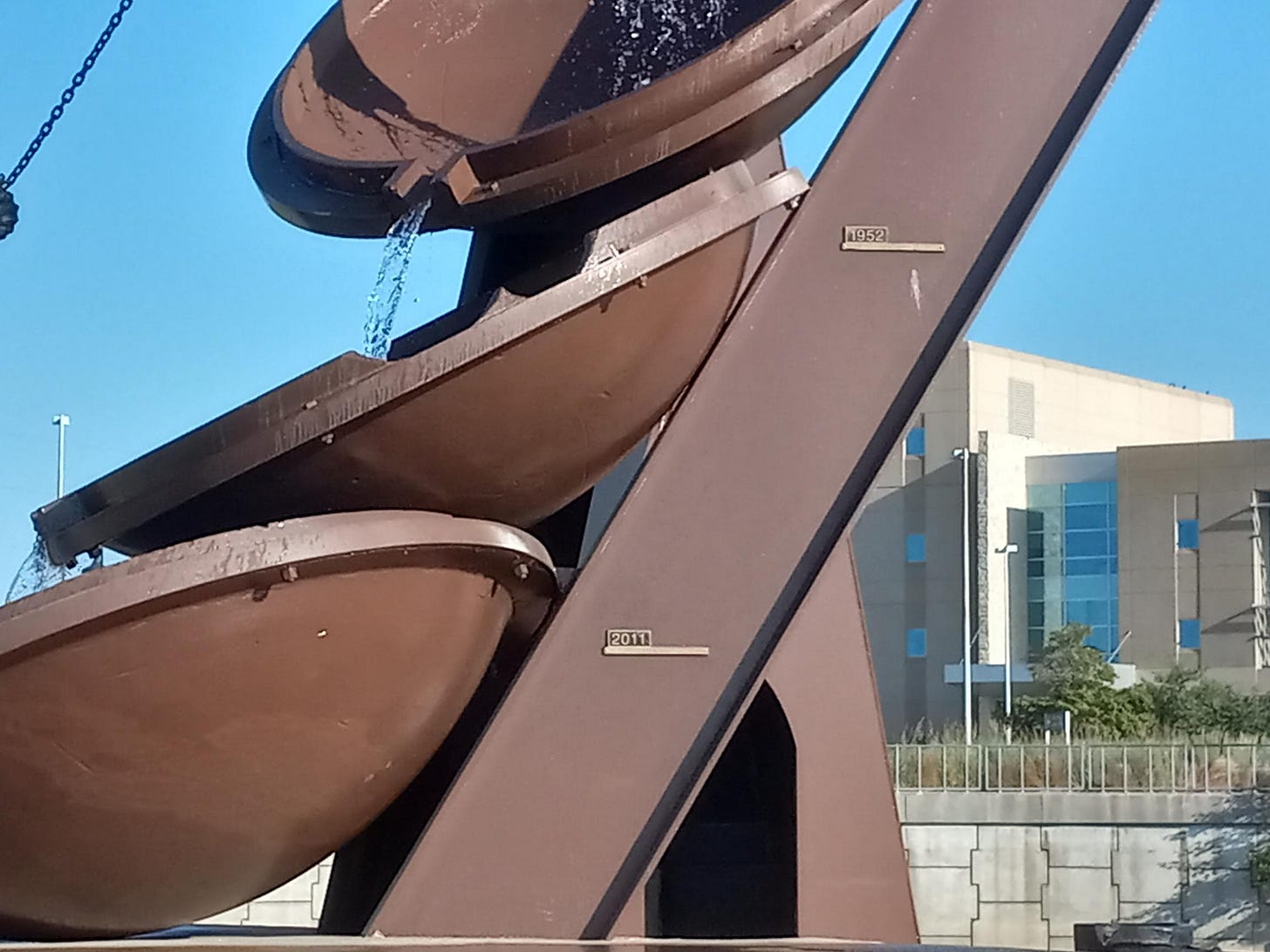

The other sculpture I want to mention is Labor, found in Riverfront Park. This sculpture was built as a generic “tribute to workers” monument but it achieved much greater significance during the flooding of the Missouri River in 2011. At that time people could walk across the footbridge above the river (in the background of the photo below) and watch as the floodwaters rose higher and higher, inundating most of the statue. At the water’s height the hammer-wielding blacksmith was almost totally submerged—only his fist and hammer were above water; this image became symbolic of Omaha’s struggle against the floods.

Look closely at the diagonal beam immediately to the right of the lowest bowl in the image above; there’s a barely-visible detail I’d like to mention. Here’s a closeup view.

These two marks indicate the level of the Missouri river during two major flooding events; in tandem with the nearby historical marker,3 these marks bring a subtle yet powerful sense of place to this assemblage of statuary. Can you imagine what it would have been like to see that much water flowing through the city’s riverfront? Labor thus becomes a landmark for the history of Omaha in two ways: in a general sense by its marking of the efforts of the craftsmen who built the city; and in a particular sense, chronicling the history of the river that flows past the city.

The largest, most complicated, and most interesting public sculpture in Omaha—the one I consider the best—is Spirit of Nebraska’s Wilderness by Kent Ullberg, a collection of interrelated bronze statues near the FNB tower. It is so large that I can’t show it to you in just one picture; here is a Google maps screenshot with aspects of the sculpture highlighted.

The sense of drama and narrative in this sculpture is truly exceptional. Upon getting off I-480 and heading into downtown Omaha via 14th street, we encounter this pioneer scout (right), beckoning us onward. He has already led a few other pioneer families through a treacherous gap in the hills, perhaps, and we are right behind.

But there’s trouble ahead! One of the heavily laden wagons has become stuck in the mud, and a few of the menfolk are struggling to get it out as the oxen strain at their yoke.

At the crest of the hill, a scout consults with a native guide about the trail ahead; another looks out across the wide prairie. What he sees is a group of bison who have been spooked by the oncoming settlers and are running away to the south.

The bison, in turn, have startled a flock of geese who rise in cacophonous alarm from a small body of water and then into the atrium of the FNB tower.

The whole thing is a triumph. My favorite part is this bison cow and calf (below). Their incorporation into the architecture suddenly gives the impression that the entire tableau, from start to finish, might have suddenly been transported through time and materialized directly amongst the buildings and traffic of downtown. An event like this might have occurred at this very spot! What sort of history lies buried beneath the years of time?

And that’s what I think the best civic sculpture excels at doing—evoking a sense of place and connection to the physical environment. Whether it is through invocation of the particular events of the past (Labor), a place’s generalized heritage and history (Spirit of Nebraska’s Wilderness), or simply an awareness of the city as a distinct entity (the O! sculptures), the best civic statuary will serve to remind its viewers of their location both in space and time, and give them an awareness of what and who has occupied that space in the past. The very best civic sculpture can become symbolic of the city itself; such has happened with works as diverse as the “Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas” sign and Paris’ Eiffel Tower. Although such a symbolic sculpture has not yet been created for Omaha, there is no reason why it could not be.

Any of my readers who ever find themselves in Omaha are hereby authorized to contact me, and I will gladly drive you around the city and give you a tour of these sculptures (and others I couldn’t fit into this essay.)

What’s the best—or your favorite—sculpture in your hometown? Comments are open!

P.S.

One kind of civic sculpture I am not interested in is when hostile architecture masquerades as public art. Here is an example which I remember seeing in Omaha one time. This is not cool at all—imagine if you are homeless and you just need a place to rest, and you encounter this.

At a very late stage in the writing of this essay, I was struck by the thought that the buildings themselves might be the greatest and highest form of civic sculpture. If a building is made to promote joy and civic feeling and to add to the city’s beauty, does it not adhere to the principles we’ve discussed? Could this explain the strange creations of the new urbanism and the “starchitects”—instead of being offices and apartments they are meant to be statues? I already mentioned the Eiffel Tower, but what about the Empire State Building, London’s Shard, or the Burj Khalifa? I simply do not have time to develop that thought, and anyway this essay is already too long. But if any of my readers want to dialogue / brainstorm with me on this theme, you know what to do.

I tried to strictly limit this paragraph to my personal memories, but if you want a more objective overview of the project in its entirety you can read about it here (apparently there still is one of the J. Does on display). If you want even more information about them—and if you are into Web 1.0 design—here is a comprehensive list of the statues, the artists involved, and their original locations.

Which is, inexplicably, a concert and convention venue, and has absolutely nothing to do with hospitals or the medical profession, despite the name.

The historical marker was not present when I visited the statue on 9.5.23. I assume it was removed for renovations or repairs and that it will return to its proper place very soon.