A mineral—that is, a completely inanimate object

An art critic thinks about Conway's Game of Life, part 2

(This is the second half of a two-part essay on the artistic implications of Conway’s Game of Life. If you aren’t familiar with John Conway’s Life, you can read my description here. If you already know about it, there’s no need to read the previous essay. Thanks!)

What counts as art? Are there things which are well-made, and which exhibit a high degree of craftsmanship, yet which are still not “art”? What are “the fine arts”? Surely we can all agree that music, painting, and sculpture fall into that category. What about architecture? What about photography? What about dance? Should a line ever be drawn between “art” and mere “craft”? Can some aspects of crafts such as furniture design be artistic, yet not be art?

And what about “high” versus “low” art? Does sculpture count as more of an art than flower arranging? Is jazz more of an art than rock? Is there more art in a sonnet than in a limerick?

What about John Conway’s Game of Life? Is it art?

I’ve been puzzling over a definition of art for as long as I can remember; the above questions are the sort of thing that fills my head all the time. The generalized question “what is art?” is too theoretical for this space right now, but the last question, about Conway’s Life, can certainly be answered in the affirmative. Life has all of the features necessary for something to be an art. It is a splendid new medium for artistic endeavor, and ought to be approached as such.

What are the requirements for something to be an art? First, there has to be a medium. Life’s medium is the colored squares on the grid. Then, there has to be a set of tools, techniques, and practices for making the art. In Life, the tools include the array of spaceships and oscillators that have been discovered by Life enthusiasts over the years, as well as the reactions, such as the snark and the eater, which aid in crafting the mechanisms in Life. Its techniques include the slow salvos that power creations such as Demonoid or Gemini; the conduits that transfer information from one part of a pattern to the other; and such things as the honeybit reaction at the heart of Megapixel. These are used by Life practitioners in the same way that renaissance artists used such things as perspective, chiaroscuro, and transparent washes of tinted oils to create their paintings. And if it is true that Vermeer used an optical device to capture the scenes in his most famous works, there is an analogous scenario in Life: people use software to aid in the discovery and construction of the pieces they make.

Is Life in any way similar to any of the other arts? Like poetry, Life uses a very simple medium. The technics are minimal: poetry is words, Life is black and white squares. Yet in both arts, the fundamental simplicity of the medium allows for undeniably rich and complicated creations.

Another analogy: like sculpture, Life is an art of revealed potentials. It is interesting to note how often Life artists talk about their “discoveries,” instead of their “creations.” Everything in Life is latent in the stark and minimal rules, just like every aspect of a sculpture is there, waiting, in the marble.

Life even has the capacity for stylistic variation—look at the almost representational c/5 Greyship of Hartmut Holzwart versus the clotted mass of goo that is Sir Robin (Adam Goucher, 2018), the curious block-plucking mechanism inherent in 10-Engine Cordership (Dean Hickerson, 1991), or the crablike structures that toss fire between their claws in Ivan Fomichev’s Weekender Distaff (2014). Clearly, there is room in Life for individual artistic expression.

Life enthusiasts have themselves realized that what they do is art. The above pattern, a complicated set of intertwined oscillators, was produced in 2020 by Otis Schmakel, and it is titled The Electric Scepter of Spectre, On Surrealistic Pillow. If you watch the pattern develop (which you can do here), it scintillates and pulses with vibrations. Schmakel describes it as “fine art.” It is fascinating to watch how the different oscillators conduct their activities; Schmakel’s creation is only a small selection of all the possible oscillators (here is a more exhaustive list, if you want to dive down the rabbit hole). But—there are many more kinds of artistries possible in Life.

Oscillators are delightfully intriguing, but they only explore one corner of the medium. There are other patterns that more fully exploit the game’s aesthetic possibilities. Blockstacker (Jason Summers, 1999) releases dozens of gliders and heavyweight spaceships to . . . make a single pile of blocks. The disconnect between the enormous complexity of the mechanism, and the trivial output it produces, borders on the self-referentially comedic. Vacuum Gun (Dietrich Leithner, 1997) slowly pulls an assortment of blocks and beehives into itself before spitting out an endless stream of gliders. This tractor-beam procedure has been employed elsewhere, most notably in Metapixel, where it is used as a clock to cue other parts of the system, but in Vacuum Gun the process is more of a suspense-building one, similar to the tension-and-release found in European classical music, or the beat drop in some EDM songs.

Or what about RacetrackSIX, a collaborative effort from 2016 and the most extravagantly brilliant display of coordination and synchronization I’ve seen so far in my researches1. The pattern is enormous, more than four thousand times as large as Surrealistic Pillow, and is made of several different conduits and mechanisms for modifying and redirecting a single spaceship, which, throughout the course of the pattern’s run, transmogrifies into at least seven other kinds of spaceships, splits into multiple parallel streams (which at one point spell out the phrase “LIFE IS AWESOME”), and bounces like a pinball all over the grid; after more than 355,000 generations, it is finally caught in a trap and turned into an oscillator right before entering the first conduit and beginning the cycle all over again. The whole thing is a giddy, hilarious romp, a tour-de-force display of the full range of spaceship synthesis available in Life.

But if RacetrackSIX is a baroque and florid showcase, Waterbear is spare and focused, evoking the futuristic modernist design aesthetic of 1930s-era trains and turbines. Waterbear is a giant spaceship (even larger than RacetrackSIX), made almost entirely of streams of smaller spaceships interacting with one another. The spaceships cross paths with each other, sometimes without colliding, sometimes crashing and catalyzing the next step in the process. Waterbear is an outstanding demonstration of the highly ordered, precise aesthetic that the larger Life creations exhibit.

A totally different aesthetic is demonstrated by the chaotic “fire” that envelops some Life patterns once they are set in motion. A randomly-generated soup of on and off cells will immediately dissolve into scattered still lifes and oscillators with pockets of froth flickering amongst the ruins. When I asked on Reddit what aspects of Life were the most aesthetically pleasing, there were many people who expressed their enjoyment of this reaction.

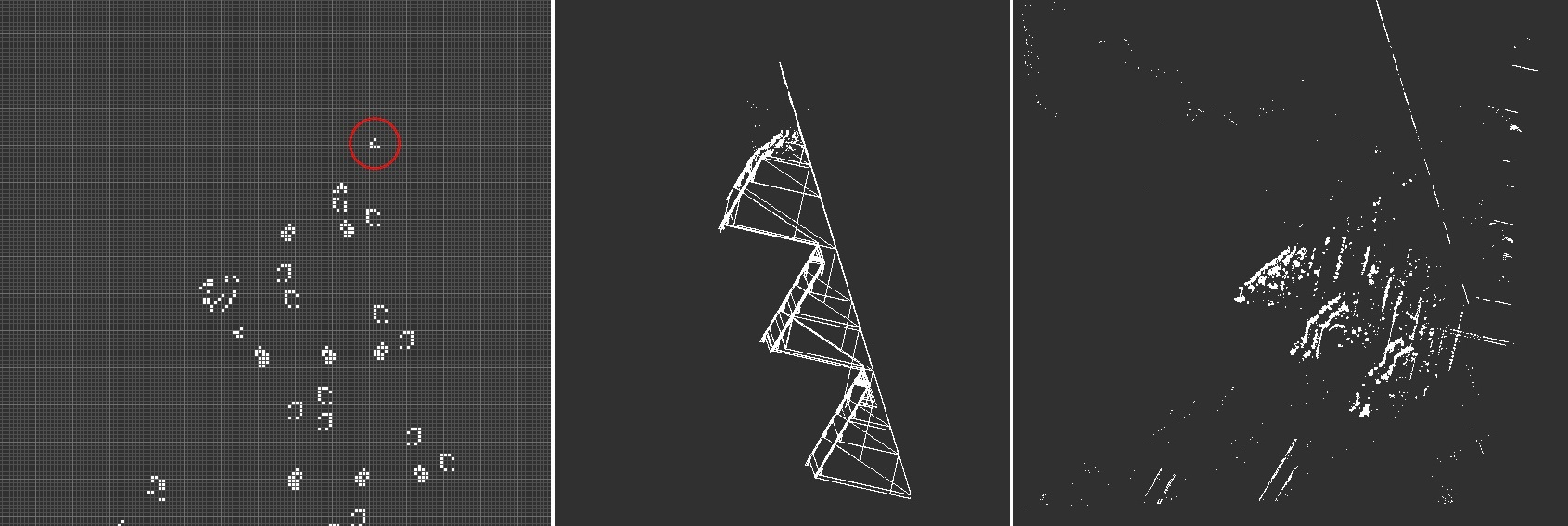

There is even an aesthetic quality to destroying a creation in Life. These immense structures are in reality quite fragile. Watch what happens, for instance, when a single extra glider is introduced at the front of Waterbear, in the images at the beginning of this essay; chaos starts happening almost immediately. As the strings of gliders are interrupted, some of their intended targets devolve into ash, and sometimes spit out additional rogue gliders, which initiate a spiral of mayhem that eventually, after more than 70,000 generations, reduces Waterbear to detritus and scattered aimless spaceships. The remains of the Waterbear fuel stack continue to float to the top of the screen, while strands of displaced gliders move away from a smoking heap of ruin in the center—which still indicates traces of Waterbear’s threefold structure but which is only as organized as the scum on a pond.

What does all of this aesthetic expression represent? What does a work in Life signify? But first, before answering that question, I have to ask what it even means for a work of art to “signify” anything at all. A poem making some observation on existence, or a painting of a landscape, both communicate and signify some aspect of reality. But there are other artworks which do not communicate propositions or representations, yet which still communicate, as Ruskin said, “a seeking for ideal truth” of some kind. There is all sorts of music, from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony to Daft Punk’s “Around the World”, which exist to convey an emotional state, and not much else.

But there is an even deeper level of abstraction. Architecture, as a whole, is an entire artistic discipline which never communicates anything that could be considered representational; buildings say things about power and relationships, but they do not speak propositionally. What about Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs of flowers—the most controversial photographer of the twentieth century produced a set of images that . . . just look like flowers.

What is signified by this painting by Mark Rothko?

This painting doesn’t have any “message” in the sense of propositional content or narrative. This painting exists only to affirm the beauty of color. It is part of the set of art objects that need no justification for their existence; they are just there, reminding us of the pure beauty of the form. That is what I think is going on with Life.

Life signifies the beauty of order. Aesthetic order can indeed be beautiful; there is certainly something sublimely satisfying in seeing all of these spaceships and gliders, colliding on cue, building a larger structure in perfect synchronization. And even in the “disorderly” soups of random cells that dissolve and splash around aimlessly, there is a meta-order to the kinds of reactions that take place. Life, bound by its profoundly simple ruleset, is a perfect method for exploring the implications of order, from the simplest to the most complex level. “Do everything decently and in order”, the Bible says; Life is certainly a means to that end.

I’d like to thank the people of the ConwayLife forums and the r/cellular_automata subreddit, who took the time to discuss Life with me. Your points were very much appreciated!

If you want to explore Life patters further, another good place to start would be Exploratorium, a collection of different patterns arranged for easy viewing. You can find it here.

This essay’s subtitle is a quote from Dostoevsky’s Demons, from the passage describing the bizarre, surrealistic, symbol-laden “poem” written by Stepan Verkhovensky. Dostoevsky’s narrator says that the poem “resembles the second part of Faust”, and in it “a mineral—that is, a completely inanimate object—also gets to sing about something.” And I don’t know a better description of Conway’s Life than that.

The link will take you to a forum post with another link to a downloadable RLE file that can be run in Golly. Sorry, that’s the only way I know of to access the pattern—it’s too large to run in LifeViewer like the others.