James Elkins maps the limits of visual cognizance

James Elkins is an art critic and historian affiliated with the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and the author of more than a dozen books on art theory and the role of the image in historical and contemporary culture. Although he approaches these concepts primarily through an art-historical perspective, his keen perception touches on much more than simply museum pictures. In the late nineteen nineties, he wrote a trio of books that, although not intended as part of a series, together outline a comprehensive theory of images and visual awareness, and especially of our inadequacies in attempting to understand what is in front of our eyes.

Why Are Our Pictures Puzzles?: on the Origins of Pictorial Complexity (1999) addresses a strange circumstance: art historians seem to be obsessed with deciphering the meanings of pictures, and this obsession is of rather recent origin. Elkins gives a comprehensive overview of the problem, first considering what counts as a puzzle, then looking at the different kinds of puzzles out there. A painting can be thought of as a puzzle because it appears to be made of many disjointed parts, and the task is to put them together, like a jigsaw puzzle (Elkins’ example is Giorgione’s The Tempest). Or it can be puzzling because we have no idea at all what the painter is trying to communicate (such as in the fêtes galantes of Watteau). There is an important difference between simple complicatedness, where the painting seems to have a message that is buried under layers of obfuscation, and more involved kinds of ambiguity, such as is present in some of Watteau’s paintings. But why does all of this puzzlement seem to be only present in the last century or so? Elkins points out that

Giorgione’s Tempesta attracted only two sentences—or rather, a faulty sentence and a sentence-fragment—during the sixteenth century: Marcantonio Michiel’s annotation “a little landscape on canvas with [a] storm [and a] gypsy and [a] soldier was by Giorgione”; and “another picture of a gypsy and a shepherd in a landscape with a bridge.” Today the painting has been the principal subject of at least 3 full books, and on the order of 150 essays and other notices.

Why is this so? Why can’t the art historians of the present day take the same stance that they apparently did in the premodern era? Elkins develops nine potential answers to the book’s title question. In my opinion, the most compelling of his answers is the third, that the culture has changed; pictures have a much fuller / more complicated position in our culture than they did in earlier times, and the discipline of art history has also taken a new significance in our current moment. But this doesn’t really address why art historians sometimes fixate on particular pictures, like the Tempesta. Elkins likens this obsession to a festering bruise; some pictures act as “injuries” to the discipline of art history, and the volumes of essays and commentary that grapple with these problematic pictures are like the inflamed and infected tissue that develops around a wound.

But the most damaging kind of puzzle, the one that really ruins our ability to understand a picture, occurs when art historians find a hidden image in a picture, and that hidden image becomes, for them, the entirety of the picture’s meaning. Art historians even have a fancy word for these hidden images—cryptomorphs. Elkins:

Paintings are said to harbor hidden lines, geometric forms, numbers, letters, ciphers and signatures, and figures of all sorts—concealed animals, people, angels and deities, heads and skulls, hands, eyes, phalluses, labia, embryos, and “Ape-men.” . . . Cryptomorphs, I think, are best understood as signs of a dire anxiety in the face of pictures. Finding something that seems to demonstrate itself may be a way of short-circuiting what is truly disturbing about pictures, and making them into merely surprising tricks.

Many times, these hidden images are very hard to unsee. They get stuck in our head, pushing out any other interpretive clues to the picture’s meaning. But are they really the key to understanding a painting? If I say that Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam contains an image of a human brain, does that negate and supplant all of the other ambiguity spiraling around the structure and symbolism of his Sistine Ceiling?

This is where Elkins’ ninth explanation comes into play: our pictures are puzzles because they are pure meaninglessness. Let’s be honest: pictures cannot convey propositional content; they are only patterns of paint on a surface. The images can allude to other things, they can remind us of other things, they can even symbolize other things, but they can never say anything in the sense that these words on a screen can say something. But what, then, are art historians supposed to do with pictures? A great deal of the analysis, discussion, and puzzlement surrounding pictures is for this reason: pictures, in their meaninglessness, taunt us by refusing to let their existence be explained.

After reading this book, I feel motivated to approach artworks much more carefully, and with a lot less ego, than I did before. Although it is important to continually ask “why?” when confronted with a work of art (“why did the artist choose this subject / this technique / this style?”), it is not a good idea to jump to conclusions about what an artist is trying to say. As Elkins explains, a cryptomorph gives us a false sense of understanding; it begs to be considered the key to unlocking the painting’s meaning, when it really doesn’t clarify the meaning at all. Just as a conspiracy theory lets us feel like we understand an otherwise random-seeming news event, a good cryptomorph tricks us into thinking that we understand an artist’s intentions, when we actually don’t.

Paintings are non-propositional, but that doesn’t mean that they cannot convey some meaning. The question is, what part of the picture is meaningful, and what is decoration? But first we need to ask, “what is a picture?”

“Most images are not art.” That is the first sentence of The Domain of Images (1999); this book can be thought of as basically one gigantic “we need to define our terms” argument. What counts as an image? Is “image” synonymous with “picture”? Is there a pure image that exists only as decoration? And similarly, is there any pure writing, conveying meaning without any decorative elements at all?

Elkins would answer no to those last two questions; all images are, most likely, representational or “meaningful” in some sense. And all writing conveys a decorative aesthetic. As Elkins says,

Even a sans serif font such as Helvetica has a recognizable shape and an expressive character, and most other fonts only seem less normative by comparison.1

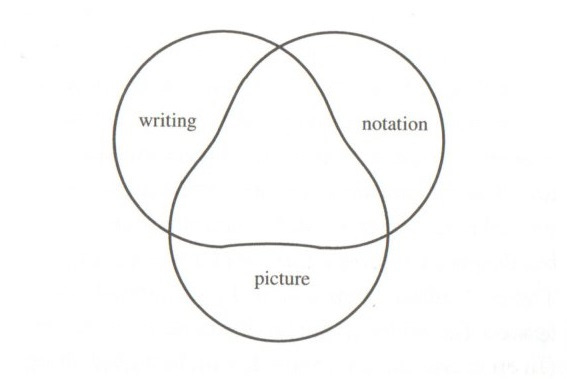

The first part of The Domain of Images is concerned with a theoretical discussion of what is included under the vast umbrella of images, and Elkins considers the various tactics that theoreticians use to come to terms with such things as scientific illustrations and musical notation. The second part of the book is a classification of images of all kinds, and Elkins employs a bewildering array of examples to illustrate his seven-part division of the domain; also he uses this doozy of a Venn diagram to divide the domain into three subsections.

This diagram is a splendid visual metaphor: writing, which we might have thought conveyed only meaning, is closely allied with, and grades into, both decoration and symbolism. The same gradation is true of the other sides of the diagram; decoration has elements of meaning in it (why else would there be so many wallpaper patterns available?), and notation is kind of like both. Some objects are difficult to classify; archeological objects like the Narmer Palette have elements of all three subdomains. Some prehistoric items are almost impervious to interpretation; the petroglyphs at the Loughcrew site in Ireland, for example, seem to deter all attempts at explanation. Elkins’ arguments and analyses are very clear, precise, and detailed, and together they carry his main point quite sturdily:

I hope that part 2 reveals enough order to make the domain of images look navigable, but I also hope, a bit more strongly, that it exhibits enough of the variousness of pictures to give pause to any theory.

That is his central axiom: that the study of visual artifacts is a rewarding one, but it must be conducted with humility. It is fascinating to follow Elkins as he goes into great detail describing his examples, and the cumulative force of his argument is that the domain of images is much more nuanced and complicated that we might first think.

In The Object Stares Back: on the Nature of Seeing (1996), Elkins carries the point to an even broader level of comprehensiveness and abstraction: vision itself is much more complicated than what we think. Elkins doesn’t mention the obvious examples of visual conundrums such as optical illusions, and instead explains some much more esoteric, yet ubiquitous, instances of where our supposed command of our own seeing is actually quite frail.

Just as pictures have latent symbolisms, and cannot be experienced as mere decoration, so too our seeing carries with it latent interpretations of what we see. What does it mean to “see” a body, or a face? Certainly we cannot “just look at” (in the sense of impartially observe) a body or a face—upon recognizing that our eyes are pointed at a face, our minds immediately start interpreting, evaluating, assessing. We start “reading” the face, for emotions or mental states of the face’s owner—but what if that face is incapable of being read? Elkins describes the effect that mutilated and deformed faces can have on the viewer—they are difficult to read, and the possessors of such faces are difficult to understand. The exact opposite happens when we see a body—we can immediately recognize bodies whenever we look for them, and we even project our desire to see bodies onto things like clouds and cars which don’t really have a body at all. Elkins discusses strange bodies, which don’t fit into our conception of what a body is, and which compel us to use anthropomorphizing metaphors to make sense of what we are seeing (for instance how people talk about the “arms” of an amoeba).

Some bodies are hard to see in a different way. Elkins considers the nude life drawing class—probably the closest thing in the fine arts to a hazing ritual. It is difficult to cultivate a stance of objectivity when observing human genitals, and students’ drawings from life class are often either excessively detailed in the pubic area, or else unusually empty of detail. Both are sure signs that our perception is not as impartial and objective as we might think it is.

Georges Bataille once said that there are three things which cannot be seen, even though they might be right in front of our eyes: the sun, genitals, and death.2 In all three instances, it could be said that these things are too dangerous to look at—the sun literally so, because it will damage our eyeballs, and the other two because we will be profoundly, undesirably affected by the sight of them. Of course, a person can learn to be completely objective about these things—gynecologists are professionals, after all, and there is no reason to believe that they are either aroused or repulsed by what they see at work. But there is a reason we don’t have public executions anymore, and why snuff films are banned on YouTube. Elkins reproduces some photographs of particularly grisly executions from the early 20th century, and says that they are the most powerfully affecting pictures he knows of. These examples are what Elkins means when, in the beginning of the book, he constructs an elaborate metaphor for what happens when we see certain objects. The objects we see influence our perception of them; to that degree it could be said that the objects have a kind of influence or even agency.

And then there is the fact that different people can see the same thing in completely different ways. Elkins:

In a church in Italy, I saw a crowd of townspeople gathered in front of an altar that had a cheap, Holiday Inn-style painting and a plastic baby-doll Jesus draped with Christmas lights. Less than twenty feet away was one of the masterpieces of Western art, supposedly full of noble and uplifting religious feeling. On the afternoon I was there, the worshippers ignored the painting as completely as the tourists ignored the plastic doll. How can I begin to understand the people who would rather worship a novelty light? What do they see?

What do they see, indeed? What do any of us see? This question brings the discussion all the way back around to the realm of art appreciation and aesthetic experience. When we look at a painting we might see something beautiful; someone else might see something ugly. A visitor to a museum might look at Giorgione’s The Tempest and think, “that’s a pretty scene”; an art historian might see the same painting and be puzzled to distraction by the painting’s essential ambiguity of meaning.

The painting, in a sense, has taken control of the art historian’s ability to understand it. The Object Stares Back is a record of instances of this control-taking, or more accurately, of our loss of control when confronted by visual stimuli. Elkins’ closing metaphor is that the objects around us are like the peacock, with its dazzling display of plumage, and we are like the peahen, enthralled and captivated by an effervescent display.

These are some of the most well-illustrated books I have ever read. Fitting with the subject of images and vision, Elkins fills these books with a plethora of things to look at, from typefaces and calligraphic flourishes to diagrams of the structure of Leonardo’s Last Supper and Velazquez’ Las Meninas, to 19th-century picture puzzles, to technical diagrams of the structure of crystals, to a reverse-azimuthal world map (one of the most difficult things I’ve ever tried to wrap my head around), to a photo he took in the Okefenokee of an alligator (which, disturbingly, cannot actually be seen in the photo), to a Brazilian treehopper insect with an extremely bizarre growth coming out of its back, to details of Monet and Renoir paintings as annotated by the delusional art historian Birger Carlström, to . . . endlessly. These books aptly deserve to be called feasts for the eyes. It’s hard to exaggerate the sheer variety and comprehensiveness of Elkins’ examples.

Although these books treat three different problems, there is a common thread running through: our fundamental perplexity when we must decipher what our eyes show us. “Why do certain paintings scream out to be puzzled over?” is actually the same question as “why do I try to interpret the emotions of every face that I see?” I think the deep-down answer to such questions is that our minds are designed to look for patterns, information, meaning. Our eyes (when they are working correctly) are merely the apparatus we use to receive information about the world around us, but our mind interprets that information and sorts for meaning. If we aren’t careful, we can take for granted this eye-to-mind path to understanding, and forget to check our preconceptions.

What should be done about these problems? Personally, I find it saddening that pictures don’t fit into the world as neatly as they used to—that they have become a wound that won’t heal or a puzzle that must be solved. I call for a new generation of art lovers to heal the bruise and show the culture the true place of paintings in society. What that is, though, I don’t know. But: there is really no place for dogmatic agendas when discussing the arts; such a stance does not respect the artist. Those who truly care about the arts should be well-known for their humility and respectfulness when talking or writing about pictures. James Elkins’ explication of the limits and biases of our visual perception helps us to see why.

Other goings-on

I wrote a guest review of Yesterday for moviewise; I and the moviewise reviewer disagree on the value of Danny Boyle’s 2019 film. That’s good; it can be tiring to only hear positive reviews, and disagreement stirs critical thought. What do you think about Yesterday? Is Ellie too manipulative? Is the film incompetent in its handling of the themes of love, ambition, and success? Do the actors’ performances fall flat?

This post’s thumbnail image is an example of pariedolia, the tendency to see things as something they are not; it’s from this collection of similar images.

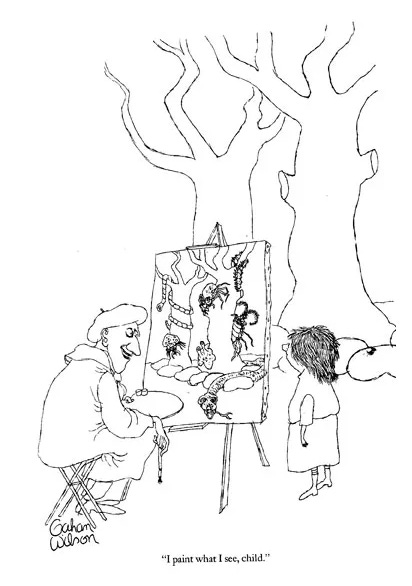

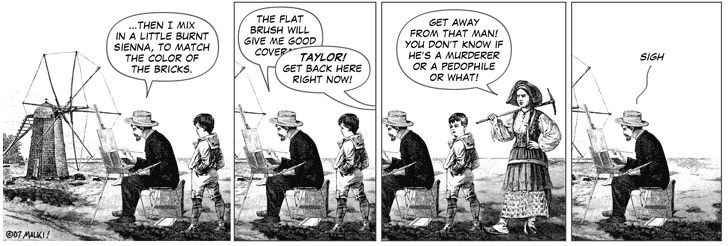

Here are two great cartoons about art and artists, the first by Gahan Wilson, and the second by David Malki.

I would propose that the swirling forms found on endpapers in 19th-century books count as pure decoration, and that a person’s own handwriting, used to write notes that only they themselves will ever read, likely qualifies as writing without any trace of ornamentation.

As quoted by James Elkins on page 103 of my copy of The Object Stares Back; unfortunately I could not track down the exact quote. If someone calls the original source to my attention I will update this essay accordingly.

I really wanted to like the movie "Yesterday". It had potential, and it's still an interesting discussion to have regarding intrinsic satisfaction vs external reward. The movie that shows this better in my opinion is "The School of Rock" (2003):

https://moviewise.wordpress.com/2013/03/05/the-school-of-rock/

I will have to read these books. The talk of grisly executions reminds me of the famous "napalm girl" by Nick Ut (Kim Phuc survived, of course). I was also reminded of Jordan Peterson's bit about whether a stump is a chair.