Errors in paintings of heavenly objects

Throughout the history of Western art there have been many painters who desired to capture an exact representation of reality—who strived to directly observe the natural world and reproduce, on their canvases, precisely what they saw. This has resulted in many fine paintings filled with strikingly detailed and accurate pictures of all sorts of things: buildings, people, textures of wood and stone and fabric, flowers and trees, animals, and even atmospheric effects like clouds, sunsets, and rainbows—but there are surprisingly few paintings of astronomical objects such as stars, nebulae, galaxies, planets, and the like. Poets are constantly being inspired by the stark and silent beauty of the heavens, but this beauty doesn’t often seem to catch the eyes of painters; at least, not to as great an extent as the rest of the natural world has. Why is this? But here is an even more interesting question: of the paintings that have been made of the heavens, why are so many of them plagued by errors of observation? Why do painters seem almost unable to paint the starry vault without making grave mistakes? Why do they so frequently get the details wrong?

Above is the first painting to depict a realistic starry sky; Adam Elsheimer’s The Flight into Egypt. Some scholars claim they can identify the specific constellations shown in this painting. To me, though, they look like a random scattering. The very prominent Milky Way cuts across the left side of the sky, but I’ve never seen the Milky Way look so straight and even; to my eyes it always has the appearance of an amorphous patchy band. Elsheimer’s Milky Way looks like an airplane trail. Besides, I don’t think the Milky Way would be visible with such a bright full moon present in the sky—even in the desert wastes of Egypt. A much more accurate depiction of a night sky is found in Millet’s Starry Night: in this painting Orion is quite recognizable to the right of center and Canis Major to the left; there are even some meteors from the Orionid shower curving across the heavenly dome. But what’s that unusually bright star just below Orion’s belt, where no star of comparable brightness is actually present in reality? I read of one critic who suggested it was a meteor zooming directly towards the viewer. Perhaps—I’ve never seen a meteor do that, but it could be possible!

Van Gogh’s Starry Night is probably the best-known example of a night sky depicted in art. Granted, Van Gogh was not trying to be realistic in even the loosest sense of the word in this painting; his usual practice was to quickly dash off his canvases in one mad rush. However it is interesting to note that he did, in fact, portray recognizable astronomical phenomena in this picture—the moon is most obvious, and Venus is just to the right of the prominent cypress tree; some scholars have even claimed they can pick out the constellation Aries in the stars. Such a claim is debatable, but it is certainly evident that Van Gogh portrayed the Big Dipper (Ursa Major) in this painting:

This is a good and accurate representation of the famous constellation, except for the fact that (according to Wikipedia) “In reality, the view depicted in the painting faces away from Ursa Major, which is to the north.”

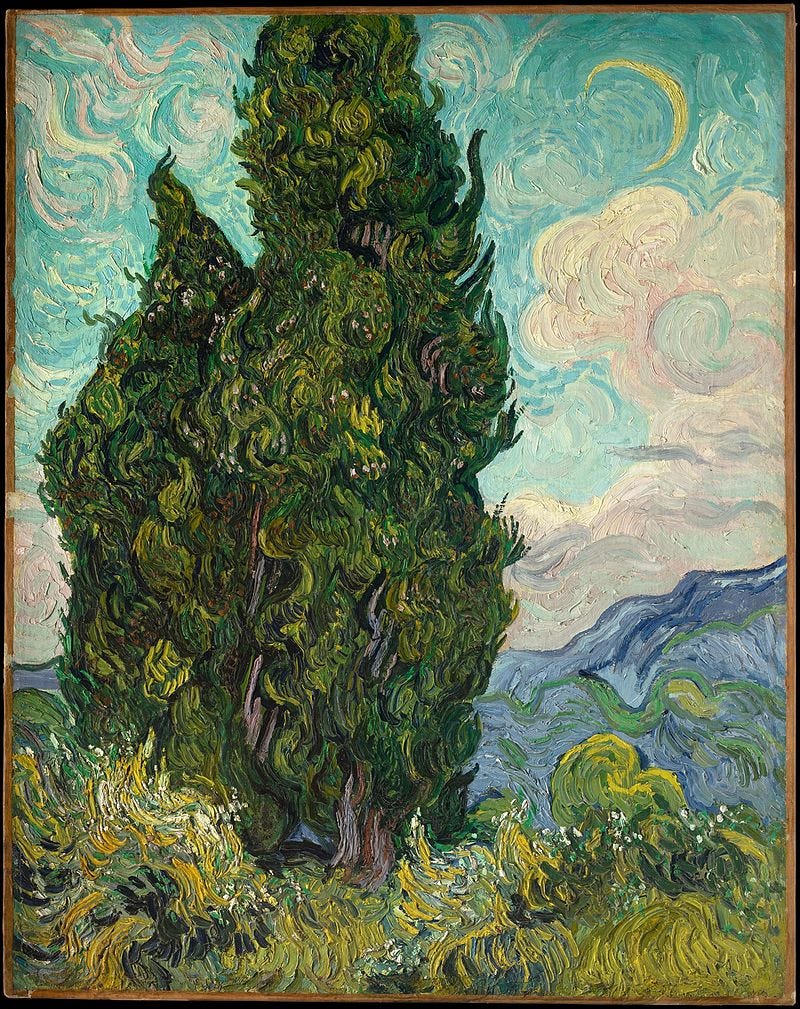

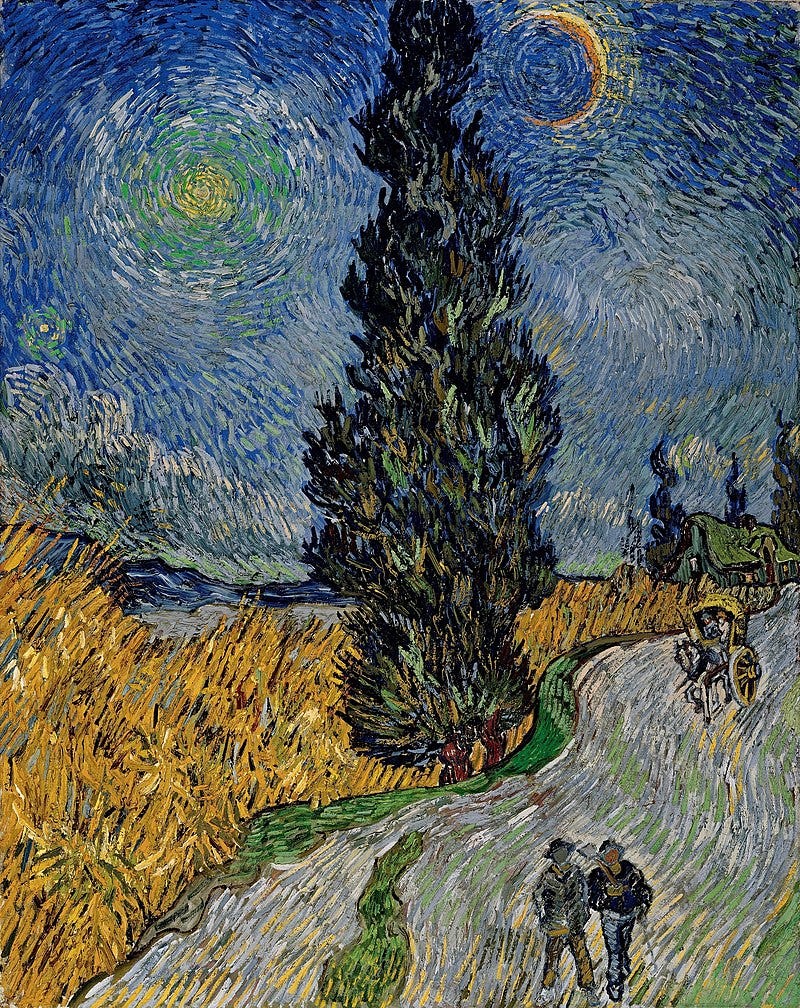

Other than in Starry Night, Van Gogh seems incapable of not making serious errors whenever he tries to paint a crescent moon.

A crescent moon would never be oriented in the sky like that. For it to be visible so close to the horizon it would have to be either just before sunrise or just after sunset—which is manifestly not the case in the first painting, considering how bright the light is—at which times the lip of the moon would be facing the horizon, and the horns of the crescent would be pointing out into the sky.

It’s actually a pet peeve of mine, this incorrect depiction of the phases of the moon in art. Since the moon is spherical, the terminator—the line dividing the dark and light halves of the moon—will always appear to us as an arc with a radius larger than that of the lunar disc. Yet there are piles of paintings with moons in them that look like this:

Which, to my mind, is not much better than this:

To be fair, there are a great many paintings which depict the moon accurately—for instance, Caspar David Friedrich’s A Man and a Woman Contemplating the Moon, William Hogarth’s The Lady’s Last Stake, or Peter Krøyer’s Summer Evening at Skagen come to mind. And it ought to be granted that artists are fond of embellishing, interpreting, and providing their impression of a scene and not the actual scene as presented to their eyes. Which is why I find it extremely curious that the Pre-Raphaelites, a group of artists dedicated to precise and exact observation, painted the moon quite inaccurately at times. Consider Ford Madox Brown’s painting The Grain Harvest.

This painting depicts a sunset scene—the sun, however, is still evidently above the horizon and shining down at a reasonable strength; the hay heaps in the background are fully lit. Why, then, is the full moon so high in the sky when there is still so much sunlight? Remember, the full moon is opposite the sun in the sky. On rare occasions it is indeed possible to see both the full moon and the sun at the same time but only when they are both very close to the horizon; the moon would certainly not be so high up. Perhaps, though, what Brown is depicting is a waxing gibbous moon. While I was writing this essay some of my children were watching and commenting, and they told me that Brown’s moon didn’t look completely full and round to them. If that is so, and if Brown was in fact portraying a slightly-less-than-full moon, I can forgive him.

But I can’t find any way to forgive William Homan Hunt, who, in his painting of a scene from Bulwer-Lytton’s novel Rienzi, depicted the moon with those excessively curled horns.

The scene occurs in full day. Look at the shadows, in particular that of the swords laid under Rienzi’s dead brother; the sun is probably about thirty to forty-five degrees up in the sky, above the viewer’s right shoulder; I’m guessing there is about one hundred and twenty degrees of angular separation between the sun and the thin crescent moon in the extreme upper left of the picture. Yet such a very thin crescent moon would never be so far away from the sun; not only that, but it would not have been visible at all in daylight as bright as Hunt is depicting.

Hunt, and the other Pre-Raphaelites, were intent on the importance of exact observation, and went to great trouble to precisely observe the scenes represented in their paintings. Legends abound, such as that of Hunt and Millais braving rain and windstorms in their excursions outdoors, and of Millais causing his model, Elizabeth Siddal, to catch a cold because he had her pose in a half-full bathtub for hours while he painted her as Ophelia. Yet . . . they were unable, it seems, to accurately observe the moon. What a strange oversight!

William Dyce, another Pre-Raphaelite, was able to accurately and precisely observe Donati’s Comet, which appears high in the sky in his painting Pegwell Bay, Kent, A Recollection of October 5th, 1858. Donati’s comet inspired several other artists as well: William Turner, James Poole, and Samuel Palmer, among others, painted it.

Why is it that painters seem to have no trouble depicting comets, but encounter difficulties when painting the moon or the stars? Could it be because comets are transitory whereas the stars have more eternality about them? Even the ever-changing moon with its various phases conforms to a set cycle of variations. But comets are rare and each one is different; there is more scope for individual artistry in the rendering of a comet painting.

Heavenly bodies are just there, unchanging; it is not possible to give an artist’s impression of them because they are the same for everyone. Basically anyone who wants to can go look at the moon or the stars for themselves. We don’t need some painter to show them to us. There are many paintings of atmospheric effects caused by the moon shining through trees or fog or clouds, but to paint just the moon would be no better than a photograph. Similarly, there are no paintings of only stars or planets. Any accurate depiction of stars by themselves would not allow any room for the “I” in this statement: “this is a record of what I saw” and where is the art in that? It would be merely draftsmanship, skill, but not creativity.

Creativity does come to the fore in paintings of extraterrestrial views of the planets. There is a sporadic tradition of paintings depicting the planets through vantage points unavailable to the average earthbound observer, stretching back through the work of such artists as Ludek Pesek, Etienne Truvelot, Howard Russel Butler, and Lucien Rudeaux, and including Donato Creci’s curious views of the planets seen as if from earth but with the detail only observable through a telescope.

But these views are all fantasies. They cannot be a record of an observation. Ludek Pesek had most certainly not sat himself down next to Saturn’s rings or on the surface of Mars when he made his pictures. These kinds of paintings seem to fall short of something fundamental to the artist’s discipline: the catching of a fleeting moment of reality.

It could be argued that all of painting is an effort to capture something that won’t last—an impression of moonlight, the faraway look on a pretty girl’s face, a sudden and unexpected vista in a landscape, the way the sun shines through the buildings and trees . . . all of it, of any kind, could be a desperate attempt to preserve and capture what is fading away or what will never be repeated . . . which could be why paintings of astronomical objects are nearly nonexistent. The stars never change. Paintings, like Millet’s above, in which the sky is part of a landscape would conform to the idea of capturing ephemerality: “the sky was so full of stars that one time, here let me paint it for you” . . . which would also explain the imprecision present in these paintings: what is depicted is the feeling, not a record of what caused it. Van Gogh might have painted his Starry Night while thinking “the moon is so big and bright, I’m going to paint how it feels to see it there in the sky . . . Yes! That’s it! That’s exactly how it feels!”

But maybe there is another reason for the imprecision and rarity we’re talking about. “The heavens declare the glory of God, and the firmament shows his handiwork,” says the beginning of Psalm 19. Could it be that artists have a feeling that to paint the high heavens would, somehow, impinge upon God’s glory? They might paint pictures of Jesus or even God the Father himself (perhaps, indeed, without his approval) . . . but maybe there’s something too wonderful about the heavens, something too otherworldly, too glorious and holy, that puts them beyond the reach of artists . . .

I don’t know! Really, all of this is pure conjecture!

P.S.

This song (the most beautiful song Brian Eno ever wrote) is sung in the character of an artist trying to draw a picture of the stars; it’s one of my favorites, I hope you enjoy it as well.

.

I love a good pet peeve.

Wow. See, that's the sort of science I would've stayed awake for in school. Quick understanding check here... are you saying moon horns are often exaggerated in art compared to the reality?