Feuilleton 2: An EXTREMELY controversial opinion regarding the making of portraits of a certain personage

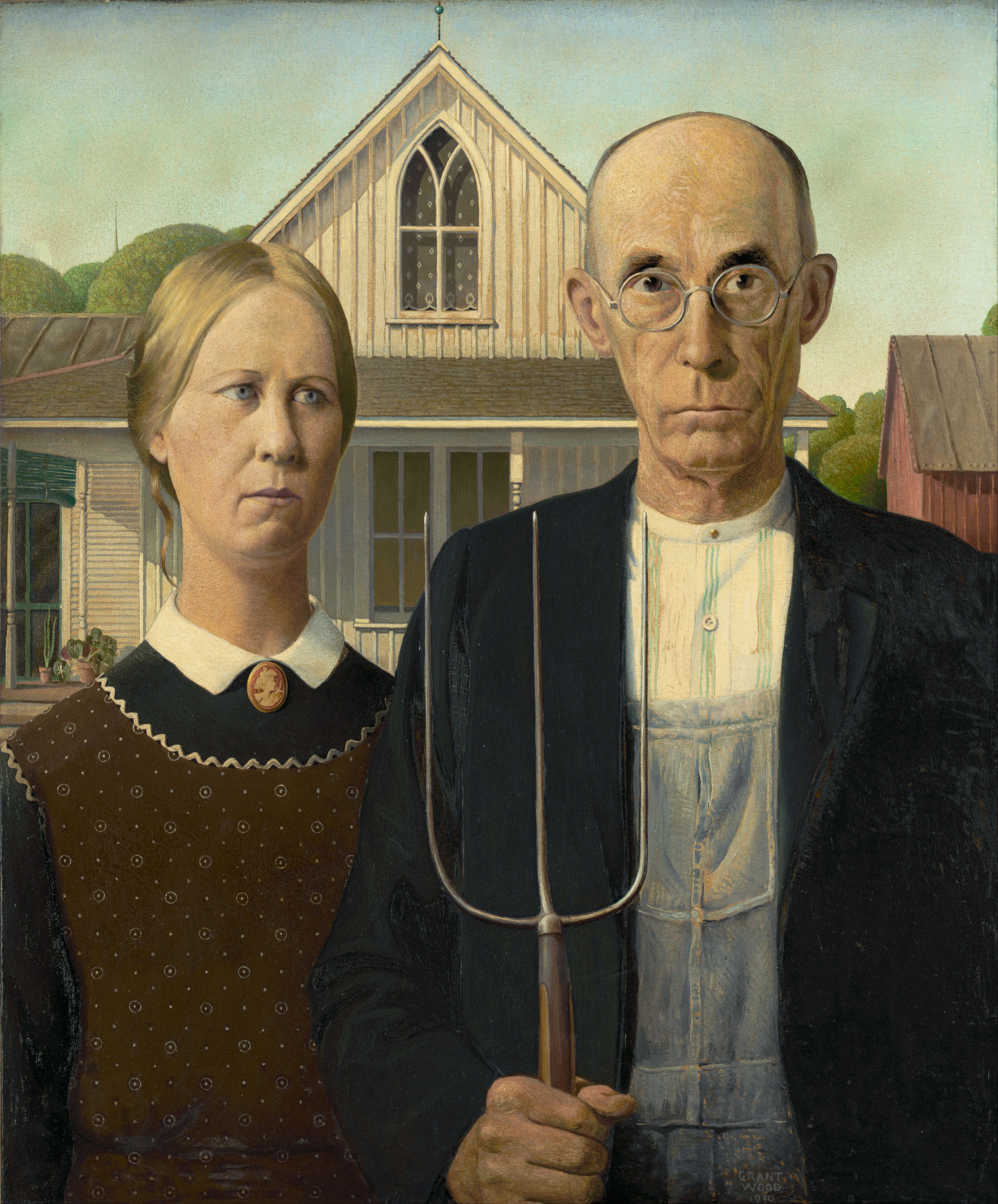

(Apologies for the clickbaity headline, but I wanted to be sure that you were aware of what you are getting into in this issue of RUINS. I’m going to start with a discussion of some paintings and photographs, and puzzle over the question of how much one should be allowed to dictate the terms of one’s own representation; in the end, I’m going to argue from the lesser to the greater to make a point on a very thorny, prickly question of aesthetics—perhaps the thorniest and prickliest question of them all. If you are Christian, then I daresay you already have an opinion on this question, even if you have never yet fully articulated your position. If you are a Christian artist, chances are you’ve already had to grapple with this question in your own practice. We'll get to the reasoning in a moment; but first, take a long, hard look at this famous painting—several minutes, if possible. I’ve got it all blown up in big size for those reading in their web browser so you can absorb the painting’s details.)

In 1930, Grant Wood, the Iowa-born, Europe-educated painter, did what artists everywhere have been doing across the ages: he saw something interesting, and he decided to paint it. He was being driven around the little town of Eldon, Iowa, by a friend, and saw a small frame house with a pretentious gothic window in the attic. He stopped to sketch the house, returned to flesh out his sketch, and decided to put into the painting “the kind of people [he] fancied should live in that house.” It was a farmhouse, of course, so he painted farm people: just plain old regular farm people.

He entered the painting in a contest at the Art Institute of Chicago and it won third prize—despite some of the judges questioning his sincerity, calling the painting “a comic valentine.” Some influential critics such as Gertrude Stein and Christopher Morley detected in the painting a continuation and reflection of the theme of satirical indictment of small-town life that was floating around at the time in American letters, in novels such as Sinclair Lewis’ Main Street or Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio.

Unfortunately, the people back home in Iowa thought the same thing. When the painting was reproduced in the Cedar Rapids Gazette, the locals were livid. Suspicious of Wood’s European training (and no doubt on the defensive after the publication of the aforementioned novels), they sensed the same mocking undertones that the critics were also seeing. Grant Wood tried to do some damage control, but with little success. He even moved back to Iowa and claimed to have close ties with the people, saying such things as “All the good ideas I’ve ever had came to me while I was milking a cow.” I strongly doubt that Wood ever intended to satirize or lampoon the average Iowa farmer, but that’s what everyone saw in the painting, and now the silly side is the only thing that anyone can see; it is certainly one of the most spoofed and satirized images in art history.

Now really, is this fair? Is American Gothic about, as one critic put it, “pinched, grim-faced, puritanical Bible-thumpers”? Is what is seen really there? The picture itself, of course, can have many meanings to many people. And even if we can’t learn anything for certain about small-town Iowa people from looking at this picture, we can at least learn something valuable from the fracas that surrounded its reception: that people are very invested in how their own image is used.

Can anything be legitimately read into a portrait? What we see there . . . is it really there? If a portrait is a lifelike, realistic depiction of a person, can it communicate character traits?

Francisco Goya was commissioned to paint the above portrait of Spain’s king Charles IV and his family in 1801. Kenneth Clark says “The Queen of Spain in Goya’s portrait of the royal family looks to us ugly, vicious and common.”1 Does she really? How can Clark read character traits into a portrait? Wouldn’t the picture only show outward appearances? If not, are we to suppose that the Queen would have allowed an “ugly, vicious, common” likeness of herself to cumber the earth? It seems to me that any evil we see in the Queen's portrait is being read into it by us.

Tabloid photographers love running images of famous people just living a normal life. Images of celebrities doing normal things fascinate us because they demonstrate something we all know implicitly—that a person’s celebrity status doesn’t correspond with their actual appearance. Consider this picture of Allen Ginsburg from 1979. He simply does not look like the wild-bearded, peyote-eating, war-protesting countercultural icon of the hippie movement that he was—he looks like a tenured university professor. In this case, who Ginsberg was—the reality of his personality and achievements—can not be seen in his image. This is the opposite of what is claimed of the Goya painting above.

Here’s one of Jack Kerouac, during the height of his fame and influence, and yet he looks like the sort of person who would change the oil in your car, not the writer of some of the most innovative books of the mid-20th century.

How about this photo of Salvador Dalí and his wife, Gala? They look like someone’s grandparents on their honeymoon. When you look at this photo, remember that this is the guy whose baseline level of personal eccentricity was biting a dead bat when he was five years old.

Wood’s and Goya’s paintings show something that may or may not be there; the photos of Ginsberg, Kerouac, and Dalí refrain from showing something that is known to exist. The whole point of me discussing all these pictures is to show that you cannot make accurate inferences about someone’s character, achievements, or personality by their physical appearance alone. If an image of a person does convey some sort of attitude about that person, it’s a fair question to ask if the painter put it there on purpose, or if, as in the cases of both the critics and the Iowans who viewed American Gothic, that attitude was brought to the painting by the viewer when they looked at the painting. Anything that we think we learn about someone from seeing their likeness may be true about them, or it may not; absent that person’s concurrence, we can’t be sure that what we see in the painting is really there in the person.

Indeed, it is possible to portray a person in such an unfavorable light that the image’s subject rebels against the depiction. Winston Churchill once vehemently objected to a portrait of him by Graham Sutherland; when the portrait came into Churchill’s possession, he refused to display it in his home, wouldn’t lend it to exhibits, and subsequently had it burned. Does Churchill have the right to object in such an extreme way to the use of his own likeness? Leaving aside the separate question of whether Churchill was right to destroy a work of art made by another person, I think it’s safe to say that if Churchill had merely disapproved of the painting, without doing anything else about it, he would have certainly been well within his rights.

The same idea motivates the respectful handling of imagery depicting minorities in America—from the removal of culturally insensitive usages of Native American iconography to the suppression and destruction of racist, disrespectful Jim Crow-era paraphernalia. The broader American culture has finally come to the point where it is racially and ethnically sensitive enough to take these considerations seriously; as a mark of respect for the humanity of others, we are in the process of getting rid of depictions of people of color which they find offensive—and that’s a good thing! Is it really possible to argue that no, people should have to put up with images of themselves which they find demeaning and rude? As a mark of respect, we allow other people to determine the ways in which their own likeness is used. Photographers do this all the time, when they ask permission to take photographs of people in public places. It is basic manners to determine how someone wants their image used before using that image.

And now here’s my big, controversial opinion: if we accord this right to people, how much more should we accord it to God himself? How does God want to be visually represented? It seems to me . . . that he doesn’t want to be represented at all.

You shall not make for yourself an idol, whether in the form of anything that is in heaven above, or that is on the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or worship them. (Exodus 20:4-5)

Since you saw no form when the Lord spoke to you at Horeb out of the fire, take care and watch yourselves closely, so that you do not act corruptly by making an idol for yourselves, in the form of any figure—the likeness of male or female, the likeness of any animal that is on the earth, the likeness of any winged bird that flies in the air, the likeness of anything that creeps on the ground, the likeness of any fish that is in the water under the earth. (Deuteronomy 4:15-18)

Lest we think these passages are only speaking of worshipping gods other than the true God, notice that the Israelites incur God’s wrath when they make a calf idol and worship him with it.2 It seems to me that the meaning of the scriptures above are that God does not want any depictions of himself to be made.

I understand that there are many people, from many traditions of faith, who would reject that interpretation. Many of my readers subscribe to the idea that images of God are perfectly okay. I am not being dogmatic; I am not saying “I, the art critic, have issued a pronouncement and solved the debate.” All I’m saying is that, at this current point, my views on the appropriateness of images of God are extremely up in the air. I have no idea what to think about the issue, but I’m leaning toward a no-images position.

There are all sorts of legitimate objections to the idea that no image or representation of God should ever be made. Are the scripture passages above talking of all depictions of God, or only of depictions used in worship? If God really doesn’t want images made of himself, why did he himself make so many? What about the burning bush? What about that snake that Moses made, which was said to be a symbolic depiction of Jesus?3 What about all the times in the Bible when God is imaged with anthropomorphic descriptors—imagery of God as a person with a “strong arm”,4 with “ears”,5 with other human traits? If we depict God using one of the similes he uses to describe himself—whether as a man, a woman,6 or even a chicken7—surely there wouldn’t be any problem with that, right? What about the fact that Jesus himself was obviously visible to the people of first-century Palestine—does that give us moderns license to portray Jesus? Is it okay to make a nativity scene with a baby Jesus in it? Is it okay to imagine a picture of God in our mind, just as long as we don’t actually physically make it? If images of Jesus are not allowed, can we still look at all those paintings by the Renaissance masters? What about icons? What about Aslan? What about movies like The Passion of The Christ? The list of puzzlements and objections grows exponentially as I ponder the question.

OK, that’s enough. I’ve kicked the hornet’s nest good and hard, and you may now freely argue with me via email. Like I said, I’m not going to be dogmatic on this issue. But I think it at least needs to be thought about by any Christian who interacts with images of God in any way.

Kenneth Clark, The Romantic Rebellion, p. 154.

Notice that, in Exodus 32:5, Aaron says that they will use the calf to worship “YHWH”—which is, of course, the name of God.