Feuilleton 5: Notes on Canon

1.

The word “canon” has two meanings. In music, canon refers to a specific form, one in which a melody is repeated and varied in an overlapping fashion, gradually building up a thick musical texture of parts which interact with each other. The type specimen for this sort of music is either Johann Pachelbel’s Canon in D or “Row, Row, Row Your Boat”; there is also a good one at the beginning of Wagner’s The Rhine Gold. Robert Fripp’s looping music, made with a guitar and two tape recorders, is also a canon.

The other meaning of canon, applicable to all kinds of art in general, is of a body of works which are considered the superlatively excellent, the indispensable, the essential: “The best that has been thought and said,” as Matthew Arnold phrased it in Culture and Anarchy. Religions group their holy writings around the concept of canon but usually with strictures indicating that no new works can be added to the collection of those already deemed sacred scripture; the cultural / literary / art world idea of canon implies that new works can, theoretically at least, be added to the august assemblage of preeminent existing ones. How that happens, though, is a process rather opaque. And what counts as “canon” is up for debate and varies depending on what specific group of people you are asking. Whatever it is, though, the concept of canon has a regulating influence on the broader artistic landscape. If an artist wishes to connect their own work to the ideas and concerns of previous ages, then the best and easiest way to do that is to quote the canon. If the canon is completely disregarded the work will have a hard time fitting in with the established conventions of its own form.

Harold Bloom wrote a book called The Western Canon which defends the idea that the literary tradition of western Europe is indeed “the best that has been thought and said” and that it is worthy of serious and sustained study by the heirs of that tradition. The Western Canon is partly a tour of the books which make up the titular subject, partly a polemic against what he calls “the school of resentment” which would topple these books off their pedestals, and partly an advocacy for books, such as Woolf’s Orlando or Borges’ Fictions, which are “kinda-canon” but which no one would mistake for being on the same level as such “core canon” stalwarts as Shakespeare, Dante, Milton, or Goethe. Bloom’s familiarity with the works which make up the canon is quite impressive and perhaps his fundamental claims about the canon’s preeminence are indeed true; but the way Bloom goes about making his case sounds less like a serious literary / aesthetic argument and more like a bridegroom telling you why his new wife is the most beautiful woman in the world. Bloom’s work is a giant exercise in begging the question. Nowhere is this more evident than in the book’s first chapter, on Shakespeare.

As a defender of the canon, Bloom can do naught else but take the Stratfordian position regarding the authorship of the plays of Shakespeare.1 He considers the Shakespeare plays to be the absolute greatest works of the western literary imagination, praising them (and their ostensible author) in the most grandiose hyperbole imaginable, such as this: “Shakespeare is the Canon. He sets the standard and the limits of literature.” He claims that Shakespeare’s “aesthetic supremacy has been confirmed by the universal judgment of four centuries” (which is a lie: Voltaire and Tolstoy both didn’t care for him). Bloom’s arguments are quite circular: since he considers Shakespeare to be the apex of the canon and the standard by which it is to be judged—and since he considers Shakespeare to have a “universalist” quality of being always and at all times applicable everywhere—anything that goes into his idea of Canon does so because it resonates with something Shakespeare wrote. “The major figures of the Spanish Golden Age brought to Hispanic literature a baroque exuberance that was already somehow Shakespearean,” he says, amongst a chapter full of similar hagiography, and I begin to share in the views of his “school of resentment” . . . but not for the reasons which that school propounds.

Shakespeare, according to Bloom, is possessed of an astonishing universality; but let’s think about that claim for a minute. “Shakespeare,” the body of work written by Shakespeare (or Marlowe or Bacon or whomever else you want to attribute them to), might be universally applicable but the same cannot be said for any specific Shakespeare play or poem. None of them are universal on their own; they derive part of their power and mystique from being written by Shakespeare . . . and that feels a little too reverent for me, a Christian, one who is not allowed to practice idolatry. And it’s true that many people don’t care for Shakespeare; are they wrong to not like him? Where is it written that Shakespeare (and by extension the whole rest of the canon) must be enjoyed by everyone, must be given a baseline level of veneration? The works of the canon may indeed speak to your personal situation, but if you can’t see that in them yet can see it in other, non-canonical works, ought you to abandon those works and go read the canon?

I object to the idea that any particular work of the human mind has inherent, intrinsic worth and value as such; those concepts are always mediated by cultural considerations. Shakespeare? For some people he is a symbol of the totalizing cultural colonialization of the academy. For some people he’s just some dead white guy, and the products of their own culture are of much greater value to them, even when they duplicate what Shakespeare already said. And there’s nothing wrong with that. Only the Bible can make a valid claim for universal value, because it is the word of the omniscient God. No human art should be treated the same way.

I do agree, however, with the idea of “the canon” as a set of works which imbue cultural literacy to anyone who becomes familiar with them. The question, of course, then, is this: which culture are we trying to understand? I’ve seen all sorts of lists bearing titles such as “Top albums you must hear before you die,” “French New Wave cinema starter pack,” “Best ‘80s teenage romcoms,” or whatever. If I want to get close to a bunch of welders at a steel mill it doesn’t do me any good to study Shakespeare; I should listen to classic rock instead, because that’s where they are. That is their culture, their canon. To them, Shakespeare is just hoity-toity stuff for snobs; genre becomes culture, and culture becomes genre—that’s just how these things happen, as cultural values and aesthetic standards change, and as we zoom in and out in the spatial and temporal dimensions. And at some point, the Western Canon becomes merely one choice among many—one statement of the melodic material of the “canon” that is the entirety of culture.

2.

There is another way canon can be approached: as a mine of ideas, allusions, and referents which can inform and embellish new works and lend structure and shape to them. One of the best examples of this way of approaching the canon is exhibited in a. natasha joukovsky’s novel The Portrait of a Mirror. Her basic plot—rich people having love and relationship troubles—owes a considerable debt to Austen and to Middlemarch, a debt which Joukovsky acknowledges. But her repertoire of allusions goes much farther than that. For Necessary Fiction’s “Research Notes” series, Joukovsky shared a list of parallel passages—extracts and quotes from other books which she incorporated into her novel. They run from fleeting references like the mention of Gatsby’s “green light” to this astounding interpolation of a descriptive passage from Moby-Dick; or, The Whale:

Nantucket! Go on Google Maps and look at it. See what an incredible corner of the world it occupies; how it stands there, away off shore, basking in the benefit of a little distance. Look at it—a storied hillock, and keenly conserved elbow of sand; a manicured wild, the ultimate background. Now double click, switch to satellite, then Street View—yes, zoom in. See the cedar shingles, cobblestones, and brick. Mosey down the Straight Wharf and examine its boats, the houses on stilts. Visit the Whaling Museum and learn of its history, how Nantucketers conquered the watery world like so many Alexanders. Is it any wonder, then, that now so many Alexanders of our watery world seek to conquer Nantucket?

An important part of the deep structure of The Portrait of a Mirror is the legend of Narcissus. Several key passages are devoted to lengthy descriptions of famous paintings of Narcissus from the western art canon (one by Poussin and two by Caravaggio in particular). But the book is also its own Narcissus legend: it’s a highly self-referential book, with widely-spaced passages being almost identical, mirror-image reflections of each other. As such it becomes its own canon. Another way this book is like the canon: Joukovsky’s tone, throughout the novel, of piercing offhand obsvervation becomes a microcosm of how the western canon comments on the broader society—how often have we been reading some great work of literature and, in the most mundane passage, have discovered the author telling us some truth about the universe of the human condition, or something about our own selves even, which we may have not even dared to acknowledge?

Joukovsky does not approach the canon as if it were some revered and hallowed temple of “The best that has been thought and said”—it instead becomes, for her, a very good, rich vein of ore to mine; she is like a hip hop DJ at the record store, appropriating other artists’ tracks and mixing them into a . . . canon . . . of different sounds and voices, from vastly different eras and genres, speaking in a strange but somehow coherent harmony.

3.

Among the chatterers, the pundits, the bloggers and substack commentators like myself, there is a lot of talk about “stuck culture”—the idea that the engines of cultural production are broken, that we are only seeing rehashes of old stuff, sequels and spinoffs and remakes and tie-ins; the same old dinosaurs of music are touring and taking up space on the airwaves, the same big names are continually discussed, and no one invests in new culture anymore. To some degree this complaint is accurate, despite the fact that very good new art is still being made (even by “legacy creators”—I mean, Beyoncé just released Cowboy Carter, one of the best albums of the century so far). The concept of “stuck culture” is often said to be the result of artists and promoters not being willing to take risks; we are, it is claimed, living in an age hostile to the idea of artists taking chances and venturing into territory which might offend. Perhaps this indeed explains most of the stuck culture phenomenon. But without dismissing these explanations—and without discounting the complex ways that creators and artists have been hurt by the invasion of hyper-techno-capitalist practices and economic models into the arena of cultural production—I would like to propose that the “stuck culture” phenomenon can also be considered as a problem of efficiency. Perhaps our culture-making engines are simply too efficient and that is what is causing culture to be stuck.

There is a certain amount of inefficiency which seems built into the very idea of art and culture. If you hang around the avant-garde circles you might think that the whole point of new art is to be innovative; but it seems there is, and always has been, a value in traveling down the old paths. From a wide-angle approach this means that subjects, media, and forms continue for a very, very, long time: no one, not even from the avant-garde, is claiming that the ideas of stage play or landscape painting or poem are archaic and outmoded and need to be replaced by something fresh and entirely new (well, maybe they are saying that about landscapes). Similarly, the “seven basic plots” keep getting recycled in books and movies, but that isn’t considered a bad thing; no one complains about “stuck culture” because we still make quest narratives, for instance. If each new work of art was expected to be entirely new and original it would cease to have any connection to the ideas and experiences of the rest of global history, and as such would be unable to find an appreciative audience.

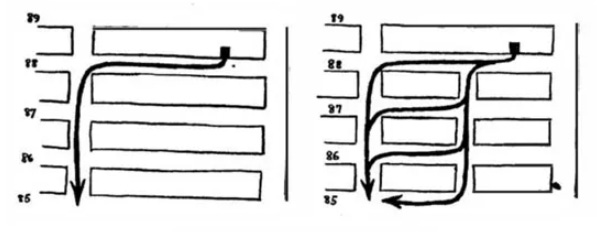

In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs advocates for what is in fact a rather inefficient approach to the urban grid—inefficient, that is, from a standpoint of getting cars from point A to point B. Jacobs is indifferent to the concerns of people who are merely driving through. What she wants in a neighborhood’s design is the ability for different kinds of people to have opportunities for interacting with each other. She illustrates her idea with this drawing of the streets around 86th and Columbus Avenue in Manhattan and depicts the route of a man who wants to walk across the neighborhood. He only has one option when the blocks are long, but if there were an additional street in between “the neighborhood would literally have opened up to him,” and there would be no impetus for the “dismally long strips of monotony and darkness” which characterize the first kind of neighborhood.

It is inefficient to have multiple ways of getting across a neighborhood, and it is inefficient to have multiple artworks depicting the same story. But there is nothing wrong with this kind of inefficiency. Just as the many ways of getting across the neighborhood in Jacobs’ first diagram allow for richness, diversity, and variety in the neighborhood culture, the many ways of telling the quest narrative or coming-of-age story allow them to relate to the many different cultures, economic realities, and shared experiences of the human condition all swirling around each other like the parts in a canon.

It is similarly inefficient for artworks to keep quoting each other, referencing each other, dwelling on the same character types, the same situations, the same jokes. How many different times have we had to endure the “mistaken identity” gag—wouldn’t a few less times still be completely sufficient? Well, no—because that repetition and variety is how art develops so much of its depth of meaning. A musical canon is a rich and rewarding artwork because the melody is subtly varied with every statement; the same subtle variety enriches culture.

I sometimes wonder if the internet-centric model of cultural promulgation is too efficient in the same way as the long blocks which Jacobs mentions feeding all traffic into one “bland, monotonous” collector road. A global platform is an efficient way to transmit information; but it also risks having a levelling effect which promotes a contextless, “current thing” mentality, robbing people of the variety and perspective that old culture can provide. Who is still reading old books or listening to old music? The algorithms are ready and willing to push the very newest cultural products at us whether we want them or not.2

For these reasons I think the “stuck culture” complaint both goes too far and not far enough. Isn’t it the height of stuck-ness when we are all on the internet talking about “the current thing,” the newest album by Taylor Swift or the newest one-man show by Jeff Koons, while ignoring the productions of the local scene in our own hometown? Meanwhile: “Stuck Culture!” the commentariat cries as soon as the latest Star Wars tie-in hits the streaming platforms; but so what, we don’t seem to mind going to plays attributed to a guy who died about a bazillion years ago—

On the question of authorship, the book to read is Elizabeth Winkler’s Shakespeare was a Woman and Other Heresies, which is one of the most entertaining books of literary scholarship I have ever read; it convinced me that Shakespeare isn’t Shakespeare.

To be clear I am not saying that we are, in fact, existing in an era without any ties to the past—but it is a possible danger that we must keep in mind.

Stimulating and steadfast as ever! The canon wars get tedious because they become rankings of taste, which become subjective passions masked in objective authority.

I will have to defend Shakespeare's appeal, though not what Bloom seems to be saying in near-religious fervor that I (on the terms you name) also reject. The plays of Shakespeare do present a grand "set of works which imbue cultural literacy," evident (I think) in their staying power for new "rich musical texture[s]" across time, cultures, and cultural contexts. Anyone who derides them as something narrowed to only English or Western greatness will have to overlook their masterful adaptations by Kurosawa, for one. As to perceptions of elitist value that your welders might feel, those aren't fully true to the plays themselves—enjoyed heartily in their day for their bawdy humor and sharp characters by people with far less education than any American in 2024. Could we blame the academic canon-izers for creating this dim perception of a Shakespeare only fit for scholars? Sure, the way we could blame school curricula for making fiction into homework. But the ranking of canon necessitates an in-group-out-group dynamic which usually reduce the texts being ranked to something beneath their actual value.

And on the subject of scholarship versus mass culture: Shakespeare wasn't and isn't high-brow at all times. Most Americans in the last 30 years will know Hamlet via The Lion King, for instance. And Twelfth Night via She's the Man, the Amanda Bynes movie from the aughts. Again, his plays have a staying power not seen in many other texts.

This is so good (and not just the parts about Portrait) that I’m willing to forgive the misspelling of my name.