Feuilleton 8: Unrelated thoughts about Caspar David Friedrich in three different contexts; also, some music recommendations

1

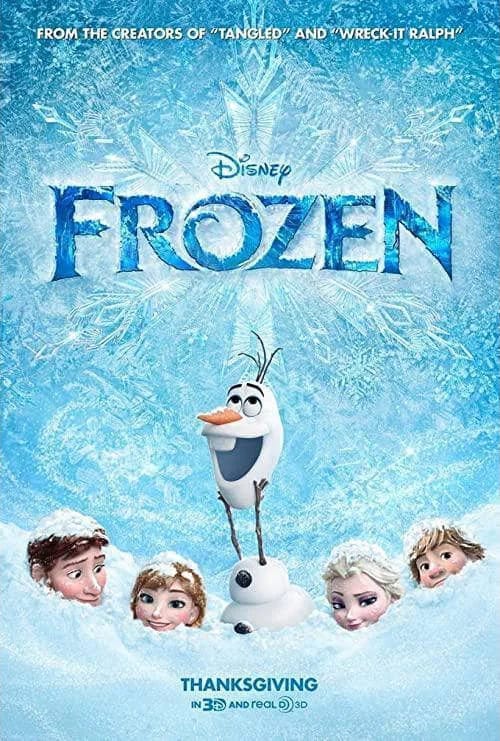

Imagine going to the theater on Thanksgiving afternoon 2013. You’ve had your giant feast of turkey, pie, and cranberry sauce shaped like a can; you’re so stuffed it almost hurts to move. You’re going to hit all the department stores at six o’clock tomorrow morning but right now you just want to do nothing, to sit around and take a nap while watching a movie. There’s a new Disney cartoon out . . . sure, let’s go watch that. At what point in the experience do you realize “whoa, this movie . . . is good.” For me it was the “Do you want to build a snowman” song, in the last verse, when Anna and Elsa are weeping together on either side of a closed door. That did it for me; at that moment I knew Frozen wasn’t going to be another lackluster effort in the same vein as Bolt, Brother Bear, or even The Princess and the Frog.

Looking at the previews, posters, and allied marketing for the two Frozen films gives me the impression that even the Disney executives didn’t really expect the first movie to be as overwhelmingly popular as it turned out to be. The previews—especially this one—have an air of charming silliness about them that is entirely absent from the promotional material for the second film. It’s as if the folks at Disney looked at how meaningful the film had become to so many people and thought, “we need to level up our game a little for this next one; these movies are important in a way we didn’t anticipate. This next film needs to have a good deal more gravitas about it.”

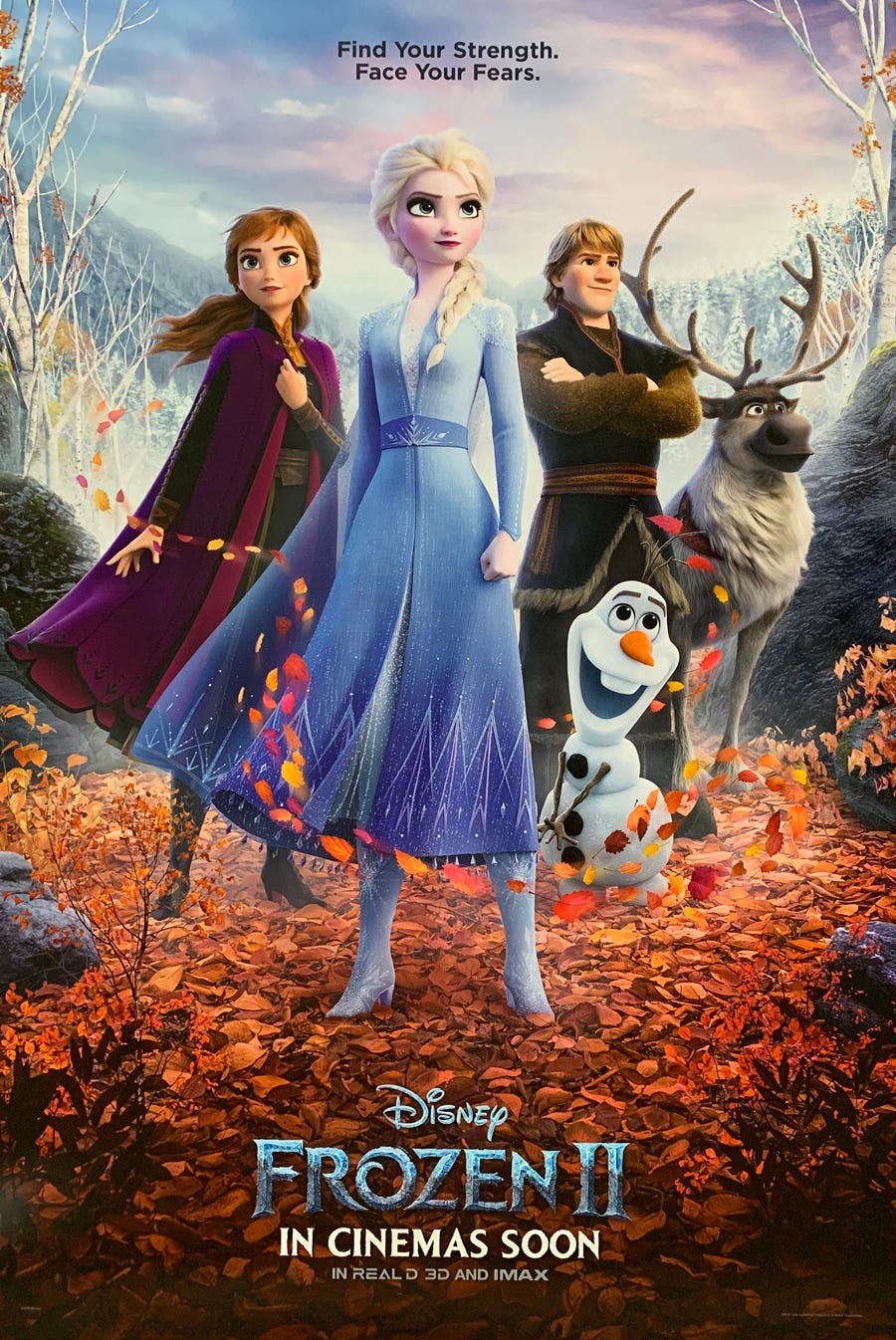

Et voila: if you were eight years old in 2013, watching Frozen for the first time, you probably identified more with Anna than with Elsa; maybe, even, more with Olaf than either. But in 2019 you aren’t eight anymore, you’re fourteen. And guess what: your cinema heroes have aged with you; now, instead of looking like this—

—they look like this:

—full of a confidence which comes with greater maturity mingled with a wonder and a seriousness that simply wasn’t present in the marketing for the first film. The film posters for Frozen II aren’t promising a reunion with our goofy, lovable friends; this time, those friends have got an important mission to attend to—and we get to watch them as they accomplish it. What are they looking at? What do they see? Will you get to see it with them?

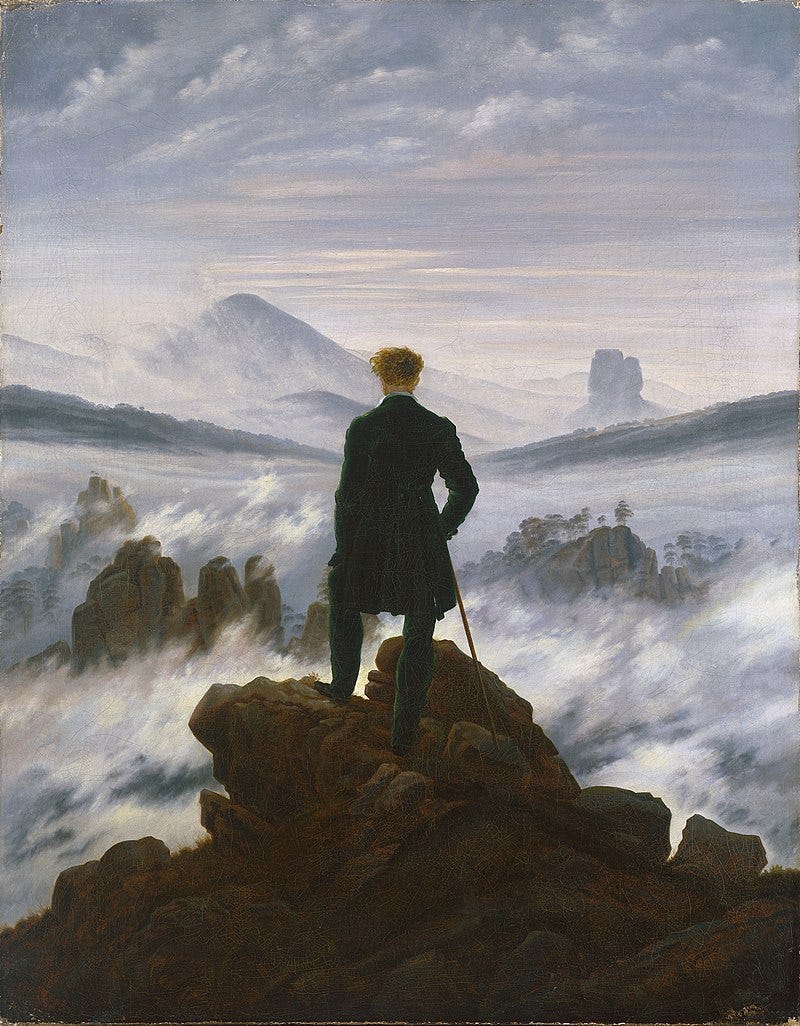

The Frozen II posters bear a significant resemblance to Caspar David Friedrich’s The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, the iconic image of German romanticism. Paul Johnson, in The Birth of the Modern, mentions this painting in the context of the cultural changes sweeping through Europe at the opening of the nineteenth century, changes which Friedrich (along with such romantic poets as Wordsworth and Southey) was not fond of at all. Johnson sees in the wanderer “a symbol of humanity contemplating the new world taking shape. You cannot see what the man thinks of what he observes: he turns an enigmatic back to the viewer.” Perplexed he is, perhaps; the future, murky and immense, spreads out before him—and us—inexorably, and we are only partially able to guess at the form it will take. It’s difficult to say whether we should look on it with wonder, or with horror.

I find it significant that, in the posters above, Anna and Elsa and the rest of the Frozen crew are shown facing us. We see them but we don’t see what has evidently captured their attention. This is the reverse of the situation in Friedrich’s painting: we aren’t shown the wanderer’s reaction to what he sees, but we can at least see it with him. We can come to our own conclusions about the future state of civilization and society, conclusions which might be different from those of Friedrich; the painter is inviting us to ponder our world but is not telling us what conclusions to make from it. Such is not the case with Elsa and Anna. We are not told what they are contemplating; we must be satisfied with watching them, watching their reaction to whatever is in front of them. Their takeaway becomes our takeaway. Their understanding of their situation becomes more important than any understanding we might have of it. We are not invited to come to our own conclusions. We are being told what to think.

2

Friedrich once said “The artist should paint not only what he has in front of him, but also what he sees inside himself.” Wise words, Caspar! But I wonder if perhaps the principle has been taken too far. As with all aspects of Romanticism, this edict has been deployed to an excessive degree these days: oftentimes it seems that artists are unwilling or unable to depict anything that doesn’t spring from the depths of their souls—or at least, that doesn’t come from some deeply-held conviction. Their worldview colors their world and makes subjective interpretation more important than objective facts; and artists, steered towards the artivism1 espoused by art schools, galleries, and residency spaces, view reality in the same way that a laser-focused redditor or twitter junkie will push for their pet belief or project out of all proportion to its actual relevance in the world. In literature this tendency manifests itself as autofiction. Recently I read about Karl Ove Knausgård’s My Struggle—a six-volume set of “novels” which are mostly a record of the artist’s own thoughts and feelings over the course of his own life. Reviewers have called it our generation’s version of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time; other reviewers have said it is overindulgent twaddle. I wouldn’t know, not having read either work. But I do wonder if the autofiction principle is some sort of perversion of Friedrich’s axiom, as well as of the old dictum that writers ought to “write what they know.” To do so would entail either writing about what you already know, or writing about what you learn through doing research. But if writers are reticent to do research (as Tom Wolfe claims in “Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast”) or to becomes intimately familiar with the minds of other people (highly likely in today’s socially atomized age), “write what you know” becomes “write about yourself” . . . hence, autofiction. Perhaps Friedrich’s adage ought to be refreshed and contemporized, to read “Artists should depict not only what is inside themselves but also the world in front of them”?

3

The first of the aphorisms at the front of Kierkegaard’s Either / Or goes like this: “What is a poet? An unhappy man who hides deep anguish in his heart, but whose lips are so formed that when the sigh and cry pass through them, it sounds like lovely music. And people flock around the poet and say: ‘Sing again soon’ — that is, ‘May new sufferings torment your soul but your lips be fashioned as before, for the cry would only frighten us, but the music, that is blissful.” Here is one of the supreme ironies of artistic practice: the pain and anguish felt by another human being, when turned into art, becomes for us merely an item of aesthetic contemplation—and the opportunity to empathize is eliminated. There is always some sort of distance between the emotions of the artist and the final artistic product—sometimes that emotional gap is unbridgeable. I’m sure I’m not the only artist who has felt a grief that is much too near to make art about. To do so would almost seem like selling out to the muse, if such a thing is possible: can’t the artist have any private feelings—or must they all be transmuted into art?

In This Side of Paradise, Scott Fitzgerald has his hero, Amory Blaine, make a similar observation about the “Dark Lady” in Shakespeare’s sonnets 127 to 152. Amory considers “how little we remembered her as the great man would have wanted her remembered. For what Shakespeare must have desired, to have been able to write with such divine despair, was that the lady should live. And now we have no real interest in her.”2 This is another instance of the artist’s emotion being too strong to fit into the art; surely, the best thing to do, the most purely enjoyable thing to do with one’s lover is to spend more time with them, not to ignore them while making art about them. Doing so will only glorify the artist, not the object of their artistic infatuation, as Amory observed.

The reverse, though, is true sometimes in art called sentimental or kitsch. In Good Taste, Bad Taste, and Christian Taste, Frank Burch Brown considers some of Caspar David Friedrich’s religious paintings, particularly Morning in the Riesengeberge from 1811. Brown notes that much Christian art about God strives for a sublimity that quickly turns kitschy. That is because such art, made by finite human beings with their limited abilities, will always appear inadequate compared to the infinite and perfect God of the universe which it seeks to describe. This reminds me of Oscar Wilde’s quip that all bad art is sincere. Of course that doesn’t mean that all good art is insincere; but what is an artist to do when the source of their inspiration—a grief, a love, their God—becomes of less importance in the public’s estimation than in that of the artist? In the case of religious kitsch, the answer is to engage in a doomed quest: to attempt to reflect the perfect and infinite goodness and beauty of God, knowing for certain that the end will be failure—but to try anyway all the same.

0

Here’s a little collection of music I’ve been listening to this fall. I overheard the first track while I was at H&M about a month ago; I snooped around on Spotify and found a handful of other songs which seemed to project a similar vibe. After listening to them for a while they all began to sound like that surf / jangle pop that was on the rise about ten years ago so I stuck two of those kind of songs onto the end of the playlist. Also I put on Water From Your Eyes’ “Life Signs” because it’s the most audaciously inventive new music I’ve heard this year; it reminds me of Starless and Bible Black-era King Crimson. And at the end, I added Byrne / Eno’s “Strange Overtones” because it is such a strikingly good song. The singer is ostensibly describing overhearing someone try to write a song but the words are full of double meanings and it evokes a feeling of the distance that can exist between two people who are at the cusp of getting to know each other better. The song is delightfully happy and sad at the same time, and the formal structure, with its shifting chords and irregular phrase lengths, continually confounds my expectations.

Artivism: the ultimate selling out, in which any aesthetic considerations about art are completely subsumed to its political dimension. I thought the term was only used pejoratively but here it is used in all seriousness.

Actually we do: there is a whole Wikipedia page about her which includes numerous references to scholarly articles about the identity of the Dark Lady. The article advances seven different possible candidates for her identity—but let’s be honest, there’s nothing different between this sort of speculation and the fan theories that pop up around movies such as Eraserhead or The Shining.

Here's a curious synthesis between your second and third sections: depiction of "what is inside [artists] but also the world in front of them" can almost definitely apply to Either/Or, though Kierkegaard was far more than a poet. That said, his depiction of the individual attempting to approach God through his own meager subjective perception straddles both sides of the adage you have in mind.

Yes, I suspect the modern aesthetic doom loop is a result of the postmodernist dissolution of objectivity. Frozen indeed!