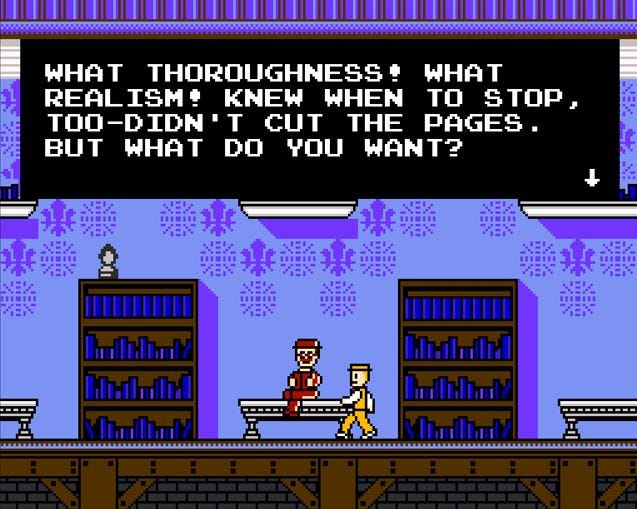

The Great Gatsby is a straight-up masterwork, plain and simple. End of discussion. Comments are closed. There is good reason it has endured for almost a hundred years—Scott Fitzgerald’s prose is gorgeously poetic without being affectatious, his pacing is tight and economical without seeming rushed, his characters are memorable without turning into stereotypes. The book has achieved the rare distinction of being taught as Great Literature to students while simultaneously being loved devotedly by average readers who pick it up on their own. It has inspired stage plays, television specials, radio dramatizations, four films, and three video games, and is well-planted as part of the cultural imagination; the first edition’s iconic cover even got referenced in a viral tweet last week.

What makes Fitzgerald a good writer in the end is his ability to get his message across in an artistic fashion, and in Gatsby he does this superbly. For this essay, I want to focus on two aspects of the novel—its narrator and its word pictures. And I want to describe the place one special scene has in the book, and what one character is meant to represent.

First, Nick Carraway. On the book’s first page he tells us that he is non-judgmental, neutral. Later, he says that he is honest. Is he? Can he be trusted? Jordan doesn't think so. And is he neutral? Does he have the right to be neutral? Certainly if any one of us found out that our friends were engaged in such debauchery as Nick discovers, it would be our duty to pull them aside and, lovingly yet firmly, admonish them to shape up. But Nick simply can’t do that—he is a fictional character, with a role to play in the development of Fitzgerald’s story. If he were to call his friends out about their behavior, he would get kicked out of their houses and the story would lack a narrator. Nick has to be a servant of the novel’s plot. But as such he becomes complicit in the evil actions of his friends; silence doesn’t equal consent, but it does equal consensus. Although Nick would disagree with me, he is just as depraved as the other characters in the book. One of Fitzgerald’s themes in his story is human depravity, and with Nick, his Everyman, an accomplice in the sordid actions of his friends, the implication is that we, too, are able to fall.

As a narrator, Nick is doing everything he can to persuade us to trust him, which of course is a giant read flag that our trust is about to be misplaced. Do we really believe a person when they say that they are superlatively honest, as Nick claims he is? Most of the time, I think, Nick is a reliable narrator, except that sometimes he tells us things that he simply has no way of knowing, such as what passed between Michaelis and Wilson the night after Myrtle’s death1. And why does he cloud in mystery Wilson’s “way of finding out” who owned the car that killed Myrtle? Nick knows the only means by which George Wilson could discover that knowledge, so why doesn't he tell us? This scene in particular is what gives me the most convincing reason for not trusting Nick as a narrator.

Throughout the book, Fitzgerald gives Nick the use of a wildly metaphorical idiom; even when Nick is relating the reminiscences of others, he colors his prose with vivid, imaginative, and sometimes completely bizarre descriptions. Tom’s yard “started at the beach and ran toward the front door for a quarter of a mile, jumping over sun-dials and brick walks and burning gardens—finally when it reached the house drifting up the side in bright vines as though from the momentum of its run.” At Gatsby’s house, Daisy admires “the gardens, the sparkling odor of jonquils and the frothy odor of hawthorn and plum blossoms and the pale gold odor of kiss-me-at-the-gate.” What is Fitzgerald's purpose in filling his book with such descriptions? (Certainly they make it difficult to capture the book’s flavor on film.) The answer can be found in remembering the important part that memories play in the book. The characters are constantly reminiscing, to the point where many of the book’s key scenes actually happen previous in time to the book’s setting of summer 1922. Gatsby himself is a very minor player in the action of that summer; he exists almost entirely in the past. He loves, not Daisy, but his memories of her, yet he finds that without a viable future, those memories are misleading and deceptive. One of the themes Fitzgerald wants to get across is exactly that—the deceptiveness of memories. And to do so he fills his book with metaphors. What else is a metaphor but a memory? Tom’s yard reminds Nick of a runner; the scent of of Gatsby’s jonquils reminds him of something sparkly. It is simply not true that the scents of flowers could ever actually be sparkling or frothy or pale gold. But they evoke in Nick’s mind a memory of something else which actually did sparkle. Fitzgerald fills his book with misleading memories to keep us aware of the deceptiveness of the past.

I can’t read the book without feeling a profound disgust for the Roaring Twenties, as Fitzgerald imagines them—I’m sure he wanted the period to come off as absolutely loathsome. And he gets his point across quite convincingly in the “Gatsby’s party” scene, the first one. We readers look through Nick’s “impartial” eyes as he plunges into a bacchanal of unrestrained licentiousness. It's the only place where the medium of film has an advantage over the book—it is so much easier to convey the noise, the waste, the sense of excess, in a visual / auditory manner. The 1974 film adaptation, directed by Jack Clayton, does the party scene excellently. But it leaves out what I think is Fitzgerald's master touch—the drunken car wreck in a ditch after the party. After the entire sickening saturnalia, after we have certainly had enough of these disgusting partygoers, Fitzgerald throws in the car wreck scene and brings us to the point of overload. It is more than enough to get his point across—it is an excess of excess. It’s as if he is saying, “Let me show you how boundless is these people’s ability to debase themselves. Look at them! They are animals!”

Gatsby himself is tainted, in our eyes, by the goings-on at his parties, even though he barely is a part of them. But, as Nick tells us, there was “foul dust floating in the wake of his dreams.” What is Gatsby, anyway? He was a son of God, as Nick calls him, and he wasted his divinity. Gatsby, with an infinite gift for hope, dreamed big, but his big dream was a waste. He made himself ridiculous trying to get the girl, a girl who only existed in his past. I think the most tragic line in the book is when Nick describes Gatsby outside of the Buchanan’s house, waiting for a sign from Daisy which never comes—as Nick says, Gatsby was “watching over nothing”. The scene is emblematic of the entirety of Gatsby’s career, which was all built up in pursuit of a nothing, an impossible fantasy which destroyed Gatsby in the end. He is a tragic reminder to us all that we have the capacity to hope, to dream, to create—but that we must, must, must be careful what we do with that capacity.

Such a narrative technique, with a narrator who is a character in the story yet possesses a sporadic omniscience, is also employed by Dostoevsky in Demons.

Solid as ever! One thing I wondered about from your characterization: absolutely, the 1920s were worth our "profound disgust," but what to make of the sense of mourning present in the novel? It's certainly there in the last line ("born back ceaselessly into the past"), and also in the sense of illusory memories that you reference. The Jazz Age was abhorrent in many respects, but Fitzgerald colors it all with a grief for what was lost in it. This sense of elegy is present in his other earlier novels as well, which makes me think that it needs more attention.

Could it be that the novel mourns that profound wastefulness you mentioned? Gatsby, possessing divine hope and superhuman loyalty, can only apply them to his own fantasy. That seems to illustrate the entire deflation of the Jazz Age, where there was so much promise for peace after WWI but also a profound squandering.

I share your admiration for this fine novel. Also, your description of the effectiveness of Fitzgerald's prose is excellent. But I think you're unfair to Nick in suggesting that he's as decadent and adrift as those he's describing. He tells us that once he returned to the Midwest after that shattering summer with Gatsby, and witnessing the Buchanans at their most deceitful, he wanted to the world to be "at a sort of moral attention."

He's discovered that we need to remain morally alert all the time, fail though we sometimes inevitably do. But he's in the novel to bear witness to that principle, to enact it. Is Ishamel complicit in Ahab's mad pursuit of the whale? No, he's our witness to Ahab's loss of moral balance. Nick plays a similar role in "Gatsby". He's not one of the story's depraved. He's our only lifeline to not becoming one of them.

Also, I've just subscribed to your newsletter. It looks as though I have some interesting reading to catch up on. Best regards.