Modern Arts Boomtown

A gallery review

Good old Omaha Nebraska—my hometown, where I’ve lived my entire life, where I’ve raised my kids and where I hope to never leave—is a boomtown. By all statistics Omaha is experiencing a period of sustained growth: jobs are up, housing starts are up, and there’s an absurd amount of new apartments popping up like mushrooms after a rain, all over town but especially in the middle of the city; some of the city’s oldest neighborhoods, places which were, only a few years ago, full of rundown, boarded-up little shops and empty lots full of crumbling concrete, have gotten gentrified all up, sprouting gastropubs, eighties-themed arcade parlors, girly wine-and-painting shops, the eternal microbreweries that follow the hipsters wherever they go; locally-churned ice cream; ephemeral things like T-shirt shops and places to get vintage vinyl; coffee shops where you can also pet cats; bookstores that also sell coffee, coffee shops that also sell cactuses and jade plants; organic grocery stores where you have to bring your own bag, jar, or can if you want to take home the flour and rice and cornmeal, and on and on.1 They’re even tearing up Farnam street to put in a streetcar line, something which hasn’t been seen in Omaha since back when guys wore fedoras all day, every day. The city library teamed up with a STEM-oriented makerspace to build a new headquarters, and it is the weirdest-looking building in town. The tallest skyscraper in the city is currently nearing completion; it will dominate what was once a sleepy downtown park full of pigeons and which has been revitalized into an urban kidzone full of crazy playground equipment and complete with a lawn at which family-friendly cartoons and such are shown on summer nights.

Busy, bustling, big—this energy is reflected, superbly and stunningly, in Mads Anderson: Spectral Dynamics, the new exhibit on view at Modern Arts Midtown, the commercial gallery run by Larry Roots and located right in the beating heart of Omaha at 37th and Dodge.

Nearly all of the art on display at the gallery’s opening reception was abstraction. The only exceptions were some Giacometti-esque filiform statues by Larry Roots himself, sneaking around in the corners of the gallery rooms. Here is another Larry Roots piece, an assemblage again influenced by Giacometti, specifically his Palace at 4 A.M; actually I don’t know, maybe that influence isn’t present, but the two works seem strongly allied to me.

Larry Roots’ works, both his sculptures and his drawings, exude an air of calm. Aside from his pieces everything on view corresponded to a general feeling of vigorous activity, fitting to the city’s mood. If this is the new art of Omaha, it is excellently apropos.

My favorite pieces were by Mykl Welch. They display a mesmerizing depth of detail and a panoply of colors, textures, and forms. These pictures evoke a bug’s-level view of the universe, with organic-seeming plantlike passages juxtaposed with grids that recede into the distance. The sense of scale is both microscopic and vast. Some of these paintings evoke the limitless vistas of prairie and sky, or maybe suburban sprawl; others layer colors and forms to claustrophobic densities, compelling the viewer to slow down and examine each square inch of the painting with close scrutiny.

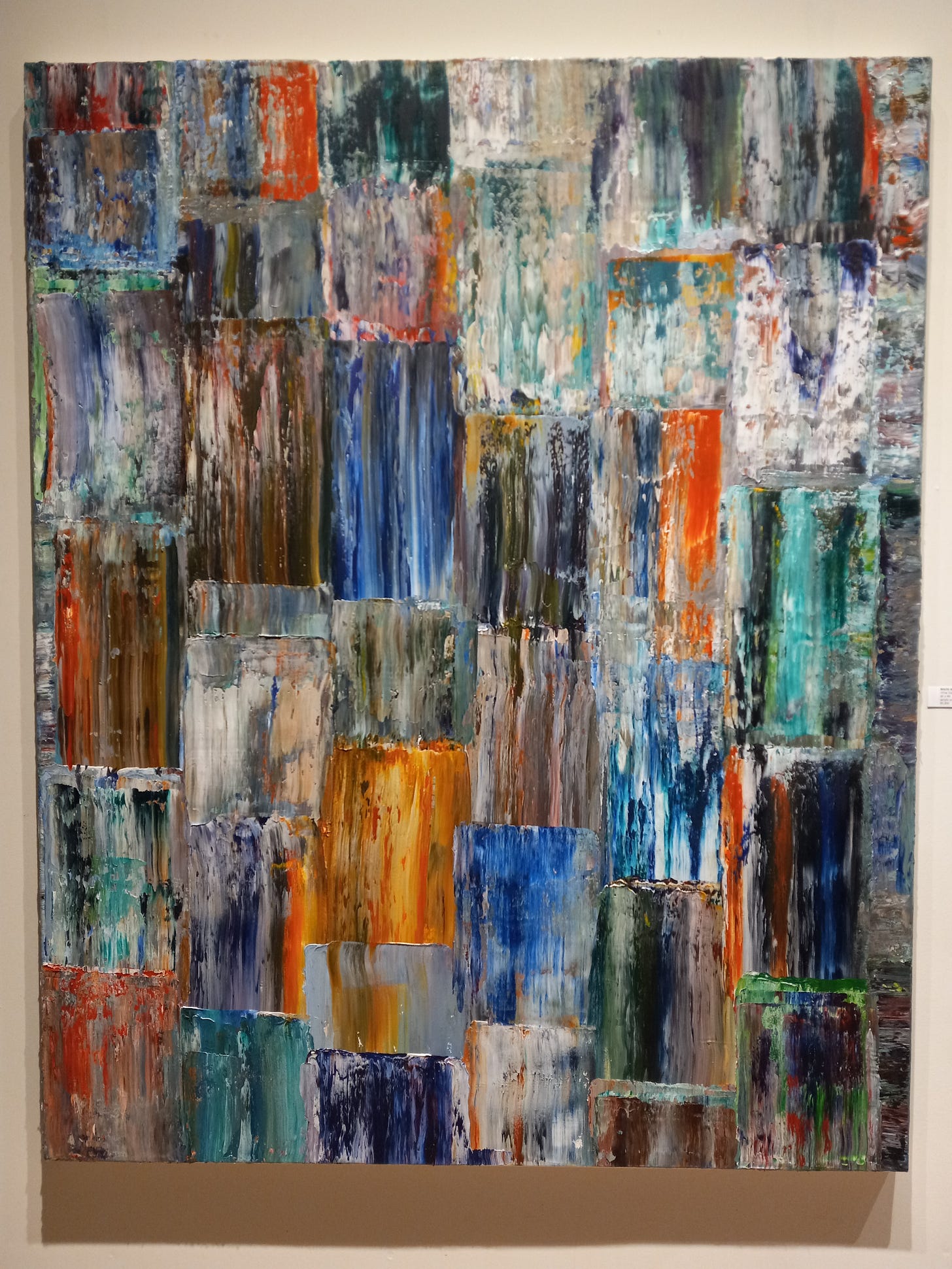

Welch’s paintings were the most formally diverse of the exhibit; and although he is very ecumenical in his choice of imagery, form, and structure, it is evident that he is still working through specific problems of aesthetics in his paintings. The other artists in the show could also be said to be preoccupied with particular problems of their art; each artist represented had a signature mood, feeling, or visual trademark to their work (I hesitate to use the word “cliché” because it has such negative connotations; none of the works here were clichéd but the artists each had distinct, recognizable “brands”—I’ll leave it to other critics to determine if that sort of thing is good or bad for artists, and for art). Some other highlights: Mads Anderson, the headliner artist, showed large-scale paintings of dense complexity, juxtaposing textures and colors in what I’m considering is a metaphor for the density, complexity, and juxtapositions of the modern urban landscape. These paintings were the most “Omaha” of all that I saw in the show: loud and brash as road construction, big enough to serve as the focal point of any public space in town—or any private residence with a wall of sufficient size (I commented to one person at the show that I myself, living in a house with mostly windows in the front room, have no place to hang such large paintings).

Anderson’s artist statement indicates that he “seek[s] to address duality” through his art, and it’s fair to ask if that claim is supported in his work. I think it is; each painting of his seemed to be defined by a larger formal structure made of minuscule units. Take The Mist, shown above, for example: at first glance it is not much more than a large gray rectangle, but a closer looks reveals its texture of multitudes of tiny marks made by brush and palette knife. This tension between the overall effect of his canvases and their individual component parts—the tension between the One and the Many, that eternal bugaboo of western philosophy—gives Anderson’s paintings a conceptual depth which is quite pleasant to behold and experience.

The only works I was not fond of were the dot-patterned textiles by Julie Owens. Perhaps Damien Hirst has simply ruined the idea of polka dots for me—that’s my fault, not that of Owens. Her color palette was much more harmonious, much less ecumenical, than that of Mads Anderson or Mykl Welch; this, coupled with her more regulated and rhythmic spatial organization, felt like a scaling back of the furious energy present elsewhere in the show.

Other works of hers played with her characteristic rigid grid structures in fun and unpredictable ways. These next two reference the countryside surrounding Omaha; as such they are the only works in the show with an explicit tie to the local geography.

Picasso, Braque, and the other early analytic cubists have obviously captured the imagination of Jaqueline Kluver, whose canvases vibrate with the most jumped-up energy of anything in the gallery. I’m also a big fan of the analytic cubists; Kluver has wisely decided not to obsess over brushstrokes as they did (Braque and Picasso always seemed to make a point, with their brushstrokes, of alerting the viewer that their works were paintings above anything else—at least, until they discovered collage). I’m interested in how these kinds of paintings are planned and executed: in Kluver’s works I can detect some hint of underlying structure, which is evident or obscured as the case may be.

I already mentioned the Giacometti-ism found in the sculptures of Larry Roots. It is a fascinating aesthetic development that Giacometti’s conception of the human form, which Sartre declared to be about despair and existentialist uncertainty—an interpretation embraced by the Christian art critics, from Francis Shaeffer to Randall Reynoso—has now become simply another tool in the artist’s kit, another way to represent people’s bodies. No one thinks of these attenuated forms as expressive of angst, loneliness, or despair; nowadays the form is most often found, on Etsy especially, in statues of dancers, symphony conductors, or happy families.

But back to the exhibit. The reception itself was very well-attended. If I could venture a coarse generalization, I would say that most of the people there were in their fifties and up and looked rich. These are the people who will be buying this art; likely, these are the people who consider themselves at the forefront of Omaha culture, either in a direct way or more subtly: business owners, in-demand professionals such as surgeons or architects, community leaders, or established scions of wealth. I should have reserved some time to interview the gallery goers but I was in a hurry because I had another commitment that same night. However, I would not be surprised to learn that the people at Modern Arts Midtown were looking for art which expressed their own view of what the city of Omaha meant to them.

Where else have we seen this idea—this desire, on the part of art patrons, to own art which expressed their deep feelings about their own place in society? Why, in 17th-century Holland, of course—the land of Rembrandt and Vermeer!

Truly, there is not much difference between the worldview and outlook of the masters of the Dutch Golden Age and the abstract works on view at Modern Arts Midtown. Both cultures desire an art which is expressive of the art patron’s own outlook on life and their place in society. The Dutch bourgeoisie—newly independent of the Habsburg empire and suddenly living in one of the mightiest and wealthiest countries in the world, overseeing a trade empire stretch all the way to the spice islands, China, and South America—wanted an art which would communicate to themselves as well as to the world at large their own prosperity and ease. As a consequence we now have masterpieces such as Rembrandt’s The Night Watch, the landscapes and cityscapes of Jacob van Ruisdael and Peter de Hooch, all those happy, contented servants of Vermeer and Franz Hals, and Jan Asselijn’s The Enraged Swan. Clearly, the Dutch were having a wonderful time commissioning and producing art of the finest quality which stretched the skills of their artists while also reflecting their own worldview, concerns, interests, and self-image.

The works on display at Modern Arts Midtown are, in a similar fashion, reflective of the pace of life in Omaha, with their kaleidoscopic variety of surfaces, forms, organizational structures. These days the communicative power of paintings has become more allusive and ambiguous; abstraction still reigns as the dominant mode in painting—yet far from being examples of the “zombie formalism” censured by Jerry Saltz, the pictures here are full of individuality, life, and a relentless, positive energy. They match precisely the mood I get when I think of my city, growing and stretching and flexing its muscle. Will we see an “Omaha Golden Age” of painting which will eventually be written about in art books? Who knows! We can surely hope, though!

All of these are real Omaha businesses, by the way. I didn’t make any of them up.