"Smokers' articles" is not a slur

How weak the Lipchitzes are! I am convinced that the place for these bronzes lies in the curio section of department stores: smoking accessories, match strikers, night-light bases…

(Henri Matisse, in a letter to Georges Duthuit, 1926)

And why shouldn’t it be, Monsieur Matisse? Why can’t smokers have beautiful or interesting things on which to strike their matches? Actually, I think there is a latent aesthetic potential here: objects to be used by smokers as match-strikers and then to be looked at. Just think about it: smoking is a very contemplative activity—especially pipe or cigar smoking—and after the tobacco is lit, what is the smoker to do? The mouth is occupied; the hands will be mostly occupied; what better situation than that of the smoker for disinterested aesthetic contemplation? Smoking will probably be done while sitting on a chair or comfy couch; therefore a smoker needs something small, something the right size for a side table, to look at while smoking. It shouldn’t be too heavy; the smoker will need to reach over and turn it with one hand while sitting on the couch, to look at the object’s other side.

The statues of Jacques Lipchitz would indeed be perfect for such a use. Lipchitz was a sculptor allied with the Montmartre community in Paris; Juan Gris, Pablo Picasso, and Amadeo Modigliani were some of his friends. He made many cubist sculptures in the late teens and early twenties, some of which can be seen below.

Another sculptor who made such objects was Alberto Giacometti. Here are a few examples of the kind of work Giacometti was doing in the late twenties, before he was discovered by the surrealists:

A few years later Giacometti would begin making small more-or-less two-dimensional objects he called “plaques” and which match quite nicely with our hypothetical “smoking accessory.” Some of these things are kind of cute!

The Matisse quote above was shared in Giacometti: Works, Writings, Interviews by Ángel González, in the context of a description of Giacometti’s quasi-cubist sculptures. The passage goes on:

Astonishing! Just what we could think of certain of Giacometti’s cubist pieces produced between 1926 and 1927, such as Composition Cubiste precisely, Personnages, Composition (Homme et Femme), or Femme Bouclier. Only the Torse of 1925-1926 could have escaped from ending up in the section of smokers’ articles in a department store, although perhaps not from that of lamps. “I saw a lot of Lipchitz at the beginning,” he told Alberto Martini, “I liked his sculpture very much.”1

At the time Giacometti was still feeling around for his own distinctive style, and it is clear he learned much from Lipchitz, though inflected with a strong exotic / primitive accent. The second sculpture—Man and Woman, from 1927—seems to be a bridge between the cubism of Lipchitz and the later works of Giacometti’s surrealist period, such as his Palace at 4 A.M. or The Cage.

The exotic / primitive strain undoubtedly came to Giacometti via the large collection of antique tribal objects displayed at the Trocadero Ethnographic Museum, only a short walk from the Montmartre and Montparnasse districts where many of Paris’ artists lived and worked. Picasso hung out at the Trocadero, too; he said that while looking at the museum’s collection of African masks he discovered the true meaning and purpose of painting. Giacometti himself seems to have taken more of his style cues from the fetishes which were being brought back from French Equatorial Africa at the time: small totemic items of a vaguely anthropomorphic character, onto which any number of associative meanings could accrue.

Why were these tribal artifacts so influential to the artists of Paris? I submit that part of their appeal lay in their unselfconscious craftsmanship; the artists making these things weren’t trying to impress a critical establishment or a network of dealers and clients. Instead they were making them out of the sincere feelings of their hearts, which gave them an innate, honest beauty. The situation is similar to that described by George Pattison in a discussion of the aesthetic philosophy of the twentieth-century Zen thinker Yanagi Soētsu:

Yanagi suggests that the conscious pursuit of beauty actually wrecks the cause of good art. True beauty can more easily coexist with clumsiness and imperfection than with contrivance and “art.” To show how beauty does not depend on conscious aesthetic culture Yanagi adduces the example of Korean Ido tea bowls. Those who made them, he says, were “poor artisans, workmen of the most ordinary kind. They were making low-priced articles. They were not giving any thought to making each piece beautiful. They threw them off simply and effortlessly.” Yet the outcome is that they reveal precisely the quality and grace of a beauty which is beyond the duality of beauty and ugliness.2

There ought not to be any shying away, by sculptors, from making such objects. I’m greatly appreciative of the artists and sculptors who occupy their time making simple and functional objects for daily use, things like vases, bowls, boxes, and the like. Artists don’t always need to make their reputation in one of the big art capitals like New York, London, or Paris; they ought to be able to stay quietly at home and make items for decorative domestic use with no condescension from people such as Matisse who seem to believe in an art-versus-craft hierarchy. Interestingly enough, Giacometti himself contracted with the renowned Parisian interior designer Jean-Michel Frank to make articles for domestic use; but he did so anonymously. “He was by far the best interior decorator of his day,” Giacometti said, “and I liked his work immensely, therefore I agreed to produce anonymous objects. In those days it was quite frowned upon. It was regarded as a sort of disgrace.”3

So . . . are any examples of this kind of sculpture available these days? I’m guessing the need for small, visually interesting, vaguely representational-to-abstract objects hasn’t died away; it’s likely that retail establishments still sell curios in a style or idiom similar to that of Lipchitz and Giacometti. Let’s take a tour of some department stores and find out.

Von Maur has a few: here is a group of three freeform sculptures that fit the bill, as well as a curious shiny metal thing that makes some amusing reflections.

At Home carries a large assortment of abstract metal wall hangings. Giacometti himself made a few of these sorts of things; his were more chaotic, though—the taste these days seems to be repetition of forms with a greater degree of regularity than is found in Giacometti’s examples.

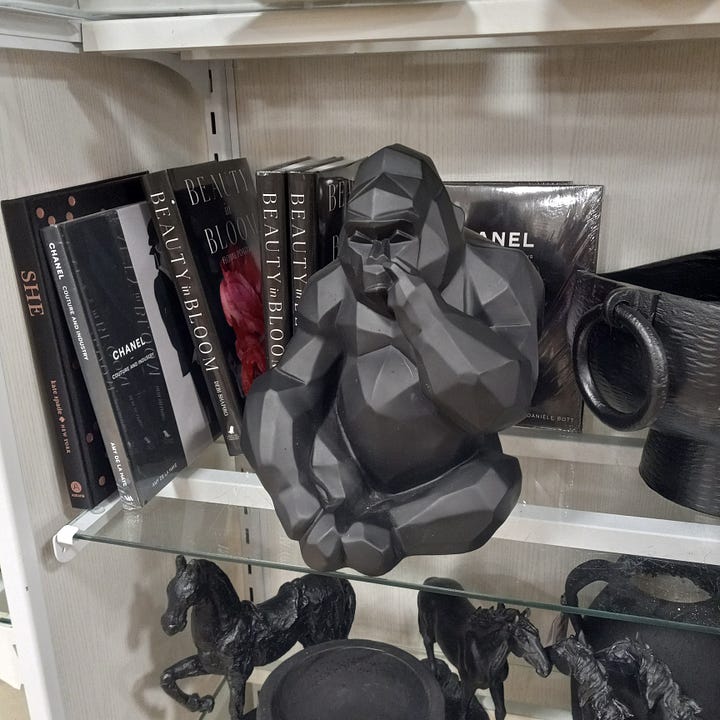

Homegoods doesn’t have any abstract sculptures that evoke the Lipchitzes we saw earlier; they did have this cubist monkey picking its nose, a proud horse, an abstracted bull, and is that one of Jeff Koons’ balloon dogs over there? Yes, I do believe it is!

House of J is a small store right next door to Homegoods with a more upscale vibe (my son once memorably described it as selling “fancy junk”). It contains some small sculptures highly reminiscent of the “plaques” Giacometti was making around 1929, as well as a filiform couple that is obviously a quotation from his postwar work. Also here is an interesting column of discs.

Of all the stores I visited, Nebraska Furniture Mart had the widest array of abstract sculptures for sale; some of these I can imagine finding their way into the contemporary art wing of a museum. I found my shiny reflective friend from Von Maur again. It looks like a jack with too many legs.

Some points to note: styles have changed and cubism is most definitely “out”; I didn’t see a single piece that looked anything like the sculptures we discussed at the beginning of this essay. Abstraction is similarly out. What I showed you is basically every abstract sculpture I could find after searching all over town for several hours; probably 95% of what I saw was straight-up representational, with chickens, for some reason, predominating (a comment on the recent bird flu epidemics and the spike in the price of eggs, undoubtedly).

I was really hoping to find some cubist-influenced match strikers or ashtrays— “smokers’ articles”—but smoking is, unfortunately, not an upper-bourgeoisie thing to do anymore. The people who buy sculptures and the people who smoke are evidently two different cohorts of people. I went into one cigar shop but they sold no sculpture of any kind at all. Maybe if I had gone into the kinds of shops which reference Cannabis sativa in their names and which advertise their selection of “custom art glass creations” I would have been more successful.

Alberto Giacometti himself was a fervent smoker; more than once I’ve encountered descriptions of how his studio floor was always littered with cigarette butts. Perhaps he was making his cubist sculptures so he himself could have some beautiful things to look at / strike matches on? He kept a copy of Gazing Head (pictured below) all his life; no doubt, during the long and fruitless years before his spectacularly successful artistic breakthrough of 1947, there were many times when he would look at it, cigarette in hand, and ponder the meaning of beauty . . . of art . . . indeed, of existence itself . . .

Ángel González, Alberto Giacometti: Works, Writings, Interviews (Ediciones Polígrafa, 2006), p. 25.

George Pattison, Art, Modernity, and Faith (Macmillan, 1991), p. 174.

From an interview with André Parinaud, published in Arts, No. 873, June 13-19, 1962.

I appreciate the mid-essay little paean to the decorative and useful creations. My wife is a potter and makes her forms according to her pieces' functions, which are so unmistakable even at a glance that I can't help be a little jealous.

As to the art-craft distinction: I have a suspicion that it (and its attendant condescension) may owe more to the critics than to the artists?

Quite fittingly, I read this article with a cigar.

One of my ash trays has a painting of a fox hunt on it. Certainly not an arresting image, but charming nevertheless.

I have custom lighter inserts for my zippo shells just so that I can keep the aesthetic experience.

Even if we don’t quite have sculptures for smoking, at least we have the art on cigar bands. One of my favorite cigars is the Sucker Punch made by Punch. It has an illustration of a lady boxer on it that I am somewhat infatuated by. To my dismay, they have apparently changed the band to a simple, plain Punch logo. Sad.