Symbolism and tradition at the UNO gallery

Personal symbolism and shared tradition — these were the two unstated themes implicit in the works of the four students whose MFA theses were showcased at the University of Nebraska at Omaha art gallery this spring. The individual artworks displayed at the show covered a wide array of mental states and approaches to this subtly stated theme, and each of the four artists dealt with the question in their own way. As usual, the opening reception was packed with people; and colored stickers near the artworks indicated that most of them sold before the night was over. Omaha is certainly appreciative and supportive of its native artistic talent.

Fatima Parra’s drawings and prints, most of which adhere to the same broadly red-centric palette, are firmly grounded within the symbolic heritage of Christianity, as mediated through Parra’s experience as a Chicana. Her work is full of Christian symbols — sacred hearts, chalices and wafers, crosses — and quotations from the Bible are written around the margins in multicolored script.

The elements of Christian spirituality which Parra emphasizes all gravitate towards a pole of suffering and hardship. The drawing at the lower left of the photo above includes a pile of skull heads creeping up from the lower margin of the page and threatening to engulf the meditative figure in the center of the composition. Parra calls these small drawings retablos, and connects them to the process of understanding her own identity, similar to how small devotional paintings as a way of explaining one’s life experience. The specific events which Parra’s art interprets are opaque to the viewer, but the emotional tone is able to shine through her artistry.

The ultimate symbol of suffering — the cross — features prominently in Broken Tablets for New Beginnings, a collage work which is itself dependent on the imagery that Parra includes in two smaller works titled Salmos 22. The two “Salmos” paintings include thorns piercing a central cross; but the larger collage work does not include any thorns.

Parra’s artist statement quotes Ecclesiastes 3:11: “He has made everything beautiful in its time. He has also set eternity in the human heart; yet no one can fathom what God has done from beginning to end.” “I constantly draw on this Biblical verse to inform my artwork,” she says;1 this kind of explicit acknowledgement of the enduring power of Scripture to inform an artist’s practice is a rare thing to find in contemporary art.

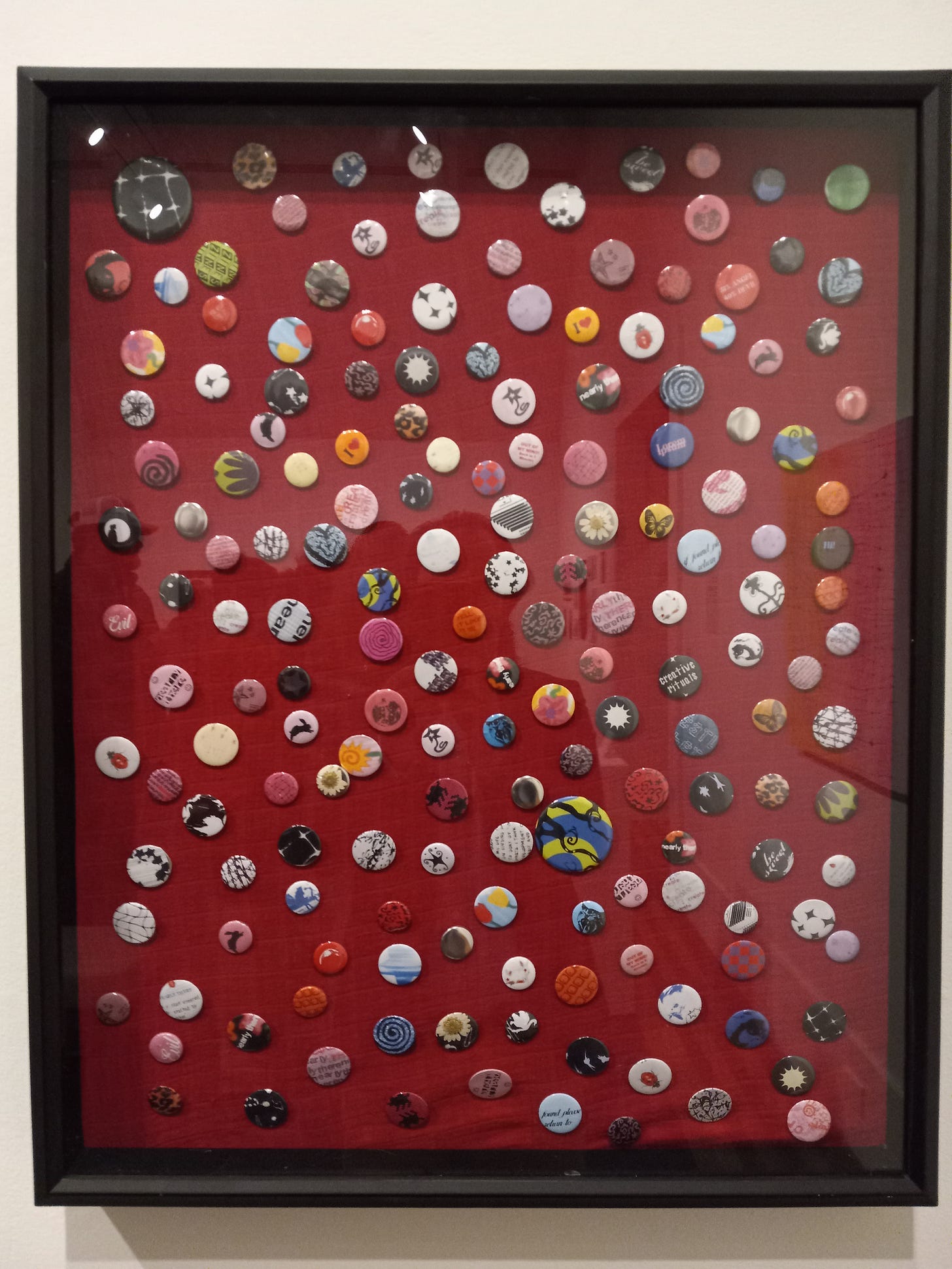

Chloe Jasperson delves into the history of zines to find the iconography of her work. The focal point of her area of the gallery is a set of small zines heavily suggestive of the style and flavor of independent underground publications of the last few decades, although the content of her zines is more reflective of her concerns about how to build community and develop one’s creative faculties.

A large framed assortment of pins was a focal point of Jasperson’s art. Each pin featured visuals from one of her zines; thus her zines themselves become a repertoire of private symbolism in service to her overall artistic project.

Jasperson also says that one of her artistic aims is to probe “the relationship between digital and analogue art.” Zine culture can be seen as a precursor to the connectivity enabled by the internet; zines allowed members of marginalized or alternative subcultures to come into contact with each other and communicate more readily through a physical medium. These days, that form of community happens most readily via digital means. But digital communication is always mediated by the platform on which it finds itself, and at times this causes conflict and discomfort. This is not the case with zine culture; every subgroup can make their own zine exactly the way they want it to be without having to adhere to someone else’s content guidelines.

Such were the ruminations of my mind as I meditated on this painting by Jasperson of a net. As a metaphor for connectivity and community — both the physical and the digital kinds — it is a particularly apt symbol.

Hayden Johnson works primarily in the medium of large-format paintings. Most of her works are self-portraits in fancy dress. She explains that her choice of costume reflects “a form of submission to the beauty standards that women must uphold.” The first painting shown here was, I thought, her most successful work; it is stripped of distracting details of scene and setting, and the focus is on the high tension between Johnson’s expression and whatever it is that she is looking at beyond the frame. In the second painting, Johnson’s pose bears an uncanny resemblance to that of Elizabeth Siddal in Millais’ painting Ophelia. I like to think this was deliberate.

Along the way, Hayden Johnson has managed to add to the number of Great Cats in Art. Cats appear prominently in her pictures as a comment on the idea of womanhood: “I find their societal reception to mirror that of a woman’s. You either love them or hate them; one can find them hostile and off-putting while others find them adorable and comforting. Rather than showing the cats as warm and welcoming, I show them as they are.” In this sense her cat might suggest a close affinity to the cat in Manet’s Olympia; what also comes to mind are the frequent cats in Bathus’ paintings of girls. The cats of Balthus, with their self-assured easy dignity, are the direct ancestors of Johnson’s cats, who are indifferent to what is going on around them.

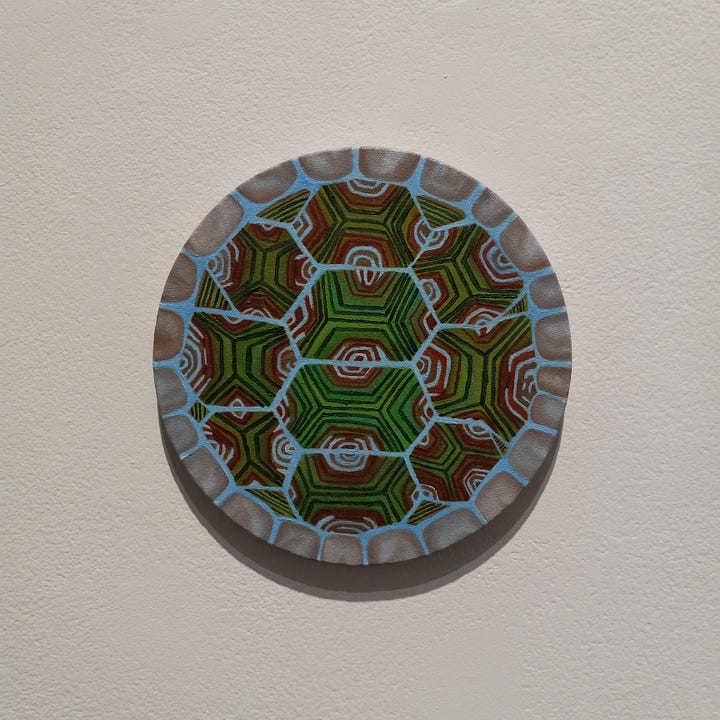

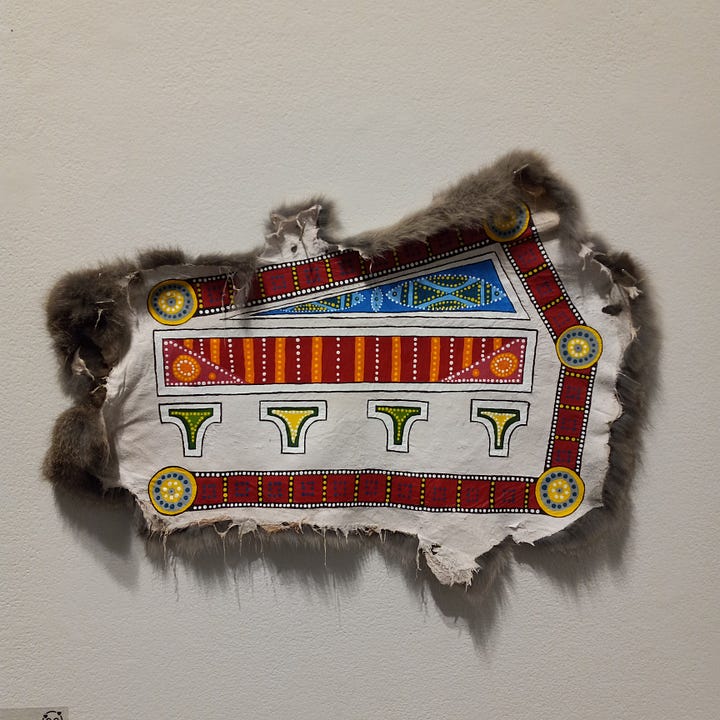

Shiloh King’s art is meant as a practice of “survivance,” a word which the artist defines as a “continuation of Native culture and traditions.” Her works draw heavily on motifs of the natural world: a turtle’s shell, the ragged edges of an animal’s skin. Some of her works on paper featured torn edges in deliberate mimicry of the rough and rippled edges of animal hides. Other images (not shown here) featured anthropomorphized representations of powerful natural forces such as cyclones and thunder.

King’s Winter Count (above) is a record of noteworthy events in the artist’s life, starting with her birth and spiraling counterclockwise. The series of symbols thus ties a life lived in the current moment with an ancient and powerfully effective method of narrative. This symbolism is necessarily private but the form is easily understood by anyone who sees it, and it is intriguing to try and guess the nature of the events symbolized. Wouldn’t it be a worthwhile activity to make a similar storyboard of the important or defining events of one’s own life?

In what ways do these four artists grapple with the weight of tradition? In Jasperson’s work — the least autobiographical of those shown — the history and heritage of zines informs the overall visual aesthetic more than the content of the works themselves. King’s artistry is heavily dependent on her indigenous heritage; Parra’s, on her religious upbringing. Johnson grapples with the visual traditions of oil painting as she seeks to describe her own situation as a woman from the plains of southwest Nebraska through art. All four of these artists are wisely aware that some kind of common ground between the artist and the viewer must be found, otherwise communication will become difficult or even impossible. Their works display a competent ability to transcend the problems of communication that all artists must face, as well as an awareness of their own place in the broader continuum of artistic expression.

Much of this work reminds me of the passage in James Elkins’ On the Strange Plase of Religion in Contemporary Art in which he discusses a visit to the studio of an artist whose work revolved around a personal experience relayed through symbolism. Elkins wonders if this student’s work, being of such a rigorously private character, might therefore be unable to speak to the concerns of a broader public. This is an important point for any artist to consider: is their own experience, as dealt with in their art, able to serve the needs of a broader group of people? If not, what is the reason for its public display?

But the four artists whose work was showcased at the UNO gallery this spring all seem to have found a way through the quandary by appropriating the ways of their respective traditions in service to their personal creativity. In this regard, their work echoes a sentiment expressed by Harold Best in Michael Card’s book Scribbling in the Sand: “Finding yourself is not a creative soliloquy, a narcissistic look into a private talent pool or some kind of aesthetic privatism. It is, instead, finding others who themselves have found others who in turn have found still others, joining humbly and hungrily with this vast community, then seeing the difference that individuality has made all around you and praying that you will end up making enough difference to warrant your citizenship in the same community.”2 This “finding others” is, in these artists’ works, their connection with tradition in its varied forms. May they all remain rooted to tradition as they continue to express themselves artistically.

Unless noted otherwise, all direct quotes are taken from the respective artists’ statements which were displayed at the gallery along with their artwork.

Harold Best, “A letter to Christian artists,” in Michael Card, Scribbling in the Sand: Christ and Creativity, page 122.

This was a great reading of the gallery: exploring the artists' works in their own turns, while connecting them together as you went through their features. This is a connection in its own right, between we readers and those artists. Thank you for enacting that.

Also, the Elkins and Sands quotations recalled the (clichéd) Eliot concepts of synthesizing both the individual talent and the traditional forms that the individual artist must respond to and work with. Funny how that synthesis comes up from different corners, different ages.