The Joslyn

For most of the past two years Omaha’s beloved Joslyn art museum has been entirely closed to the public while an additional wing was being built. The museum finally re-opened this past September. During this time the museum was given a complete rebranding: it is now called “The Joslyn,” and all signage, etc. has been visually unified with a set of custom fonts and colors. I’ve been eagerly awaiting the reopening, and my curiosity has been most pointedly directed toward wondering what, if anything, will have changed in the museum’s old wing, the original one, dating from 1931, with all the art-deco detailing. This building has been a beloved part of Omaha’s cultural landscape since it was opened—during the two-year renovation period was the old wing changed at all? What, perhaps, has it become?

During the past two years I’ve also pondered questions of what a museum’s place ought to be in today’s world. These days we have moved away from veneration of the masters of past ages; also, practically any work of art is just a Google or Wikipedia search away. Is there still a reason for museums—architecturally imposing physical spaces in particular geographic locations—to exist? Specifically, what is the role of The Joslyn within the Omaha community? How will the museum’s new addition work towards enhancing that role, whatever that might be? Can a particular vision for the museum’s role in Omaha culture be detected in the choices made during the long period of renovation? Since it’s reopening I’ve visited the museum four times. In some ways, the changes are exactly what I expected them to be. Parts of the new construction are saddening to me; parts are quite pleasant. Will you come with me in spirit, and tour The Joslyn with me?

We start at the entrance. The museum’s imposing pink marble edifice is a local architectural icon; but to get in you have to drive all the way around it and come at it from the back, as if it were an old farmhouse. The parking lot is planted within a rambling sculpture garden which I did not investigate. The entrance is rather glowering and beetle-browed, dark and quite colder than the surrounding parking lot. But immediately inside all is warm and bright. The atrium has a wide-open and inviting look not dissimilar to an airplane terminal: businesslike but conducive to lingering. Admission is free at the museum but the staff at a long counter appreciate your giving them your zip code and taking a small metal marker that affixes to your shirt front. After that little ritual we are ready to begin the museum experience proper. A very, very long couch sits in front of a huge window overlooking the south side of the sculpture garden and the original museum entrance. But that isn’t what attracts one’s attention the most—no, our eyes are inexorably drawn to the long, grand, curving stair leading to the museum’s upper galleries. Below the stair is a passage leading off somewhere else, but that staircase begs to be ascended . . . we’ll worry about that other passage later. Up we go!

After the drama of the grand stair, the upper-level open area is somewhat of a letdown, even a confusion: what now? No art is immediately visible to beckon and entice, other than a glass sculpture at the far end of the mezzanine in the café below. Did I go the wrong way? To the left, glass doors disclose what are obviously the galleries, but it feels as if entering them at this particular point would be like being plopped into the middle of something; we would have to backtrack. To the right there is what looks like a twisting passage that probably also leads to galleries, but again, no actual art can yet be seen.

Perhaps on reaching the top of the stair we should have made a 180-degree turn. Yes, that looks more promising: there is a dramatic view of the museum’s steel structure, and there, at the end of a long passage, is some art: a rather smeary-looking painting by Morris Louis.

More art discloses itself as we approach. Yes, we are finally within the galleries: the Philip G. Schrager collection, as a placard helpfully informs us. Schrager, an Omaha businessman, was a keen collector of contemporary art from the postwar period to almost the present day (he died in 2010). I’ll admit I’m not particularly fond of contemporary art, and I do question the need for Omaha, specifically, to use up a huge amount of museum space displaying it. But Schrager loved the stuff, apparently. What will we see as we look through five decades of new art . . . ?

There are a few standouts: Richard Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park #133 is probably my favorite painting in the Schrager gallery, but that’s just because I like Diebenkorn’s paintings, his attention to spaces and edges; his work is always a pleasant wander for the eye. I first encountered Diebenkorn’s work from its use by Grizzly Bear on their album Shields; since then I’ve grown to appreciate it more and more. Ocean Park #133 is mostly monochromatic, so it feels similar to the pieces used on Shields.

Tara Donovan’s sculpture Bluffs is also a standout. It is made of thousands and thousands of buttons, stacked and glued together into forms resembling stalactites. This one is interesting to me because it opens up potentials: anything can become material for interesting art, even buttons; it’s also very unassuming and not ego-driven at all. I would put this in my house except for the fact that my kids would probably break it.

Ellen Gallagher’s Soma looks like a drawing of great quantities of beans. I read the title card next to it and I’m told that it is, in fact, a comment on “the deplorable cultural phenomenon known as minstrelsy.” I’m not sure what I think about that. What was an intriguing visual design has now become a pointed screed against a historical practice that isn’t done anymore. I don’t think I would want to be reminded of this every time I were to look at this picture were it in my house or office. Am I being insensitive? Am I speaking from a position of privilege? Or am I just hoping the art in my life can be decorative without having to preach a sermon at me each time I look at it? For that is what Gallagher’s picture does.

Thomas Struth’s photo Audience 5 (Galleria Dell’ Academia) is my favorite artwork in the Schrager gallery. It is an enormous photograph on the scale of the epic historical paintings of the renaissance; it depicts a crowd of people looking up at Michelangelo’s David. The variety of expressions on these people’s faces is fascinating. Here they are, looking at one of the great treasures of Western art, a treasure that has been reproduced, sincerely and in parody, so many times that it has become a trope, a meme. Is it even possible to look at David with a fresh and untainted gaze anymore? The group of three young people in front is perfect—their faces range from half-bored and slightly cynical to awestruck.

But the range of expressions on the faces of these viewers of the David could also reflect the range of feelings expressed by viewers of contemporary art. There is probably still a canon of venerated artworks which are expected to be approached with reverence.1 But contemporary art has not entered that canon and therefore it can be approached cleanly and without preconceptions. Contemporary art is still open to the judgment of history, despite its having been embraced by the white-cube museum / gallery-industrial complex: it’s still okay to say “I don’t like it” about most contemporary art in a way that it is not possible with works by the Old Masters or the Impressionists or any of the other Great Works of the canon. Really, it’s simply not possible to claim the art of, say, Raphael is junk without being accused of philistinism—unless you are prepared to start your own art movement and put your paint and canvas where your mouth is.

Back to the gallery. Let’s try to wander around a bit. Mostly, the Schrager gallery subtly pushes its visitors along a pre-ordained route. There are gallery catalogs strewn here and there on benches so you can look at a photograph of the art that’s right in front of you. Music from a video installation about dancers wafts in and out of conscious hearing. Eventually we find ourselves in a room of works by Ed Ruscha. I must confess I’ve never cared for Ruscha’s art. He has one trick and one trick only: he can put words and letters in front of other things. If you’ve seen one Ruscha, you’ve seen them all. But: Ruscha was born in Omaha, so Omaha’s museum has a whole room of his pictures.

After the Ruscha room comes a gallery of portraits. This is the most conceptually intriguing / puzzling room for me so far, because of the jarring contrast between the placard on the wall and the actual artworks themselves. The placard states that contemporary artists are involved in “upending the notion that their painted subjects exist for audience gratification. Confidently returning the viewer’s gaze, the sitters in the paintings on view in the gallery embody artist Mickalene Thomas’s assertion that these individuals do not need permission to be present.” Yet I don’t think I would ever have thought that the portraits in the museum, or any portraits at all for that matter, are “asking permission” to be present. Portraits are just . . . portraits. They sit there, painted, on the wall; and while the real people depicted in them have intrinsic worth and dignity, their portraits, in contrast, do in fact exist for my gratification. This is some rather thick mumbo-jumbo on this placard in the gallery; the portraits themselves look more or less like all portraits, everywhere, from all times and periods.

More galleries follow. As an avowed hater of Jeff Koons I found it pleasantly surprising that my favorite work in this part of the museum was Koons’ Gazing Ball (Goya the Forge). I’m looking at a painting by an acknowledged master, but I’m also looking at myself . . . and I must admit, my own reflection in the gazing ball was much more interesting than the Goya! Is this really how I approach art—as a vehicle for my own self-awareness? Can’t the art exist on its own merits without always having to be interpreted, thought about, by some art lover? Mountains and sunsets sometimes exist only for the enjoyment of God; no person needs to be present for them to be beautiful and good. But paintings? They simply can’t exist in the world in a completely objective and depersonalized state. Ah well. I suppose this is to be expected of the sub-creations made by us humans, who can only “create” in a pale imitation of the godlike ex nihilo. Some rather heavy thoughts you inspired in me, Jeff! I salute you for that, but not for your other works, which I still reserve the right to despise!

So now I’ve seen fifty years of new art, courtesy of Phillip Schrager. Actually it seems that the last few rooms are named after other donors. I would have preferred to know when I was leaving Schrager’s collection and entering another group of works; the museum’s curators could have, I’m sure, done a better job of alerting me to that. Whatever; it doesn’t matter. I try to ignore the placards as much as possible anyway. If I need to read a few paragraphs of text to appreciate an artwork maybe I should be reading a whole book about it instead.

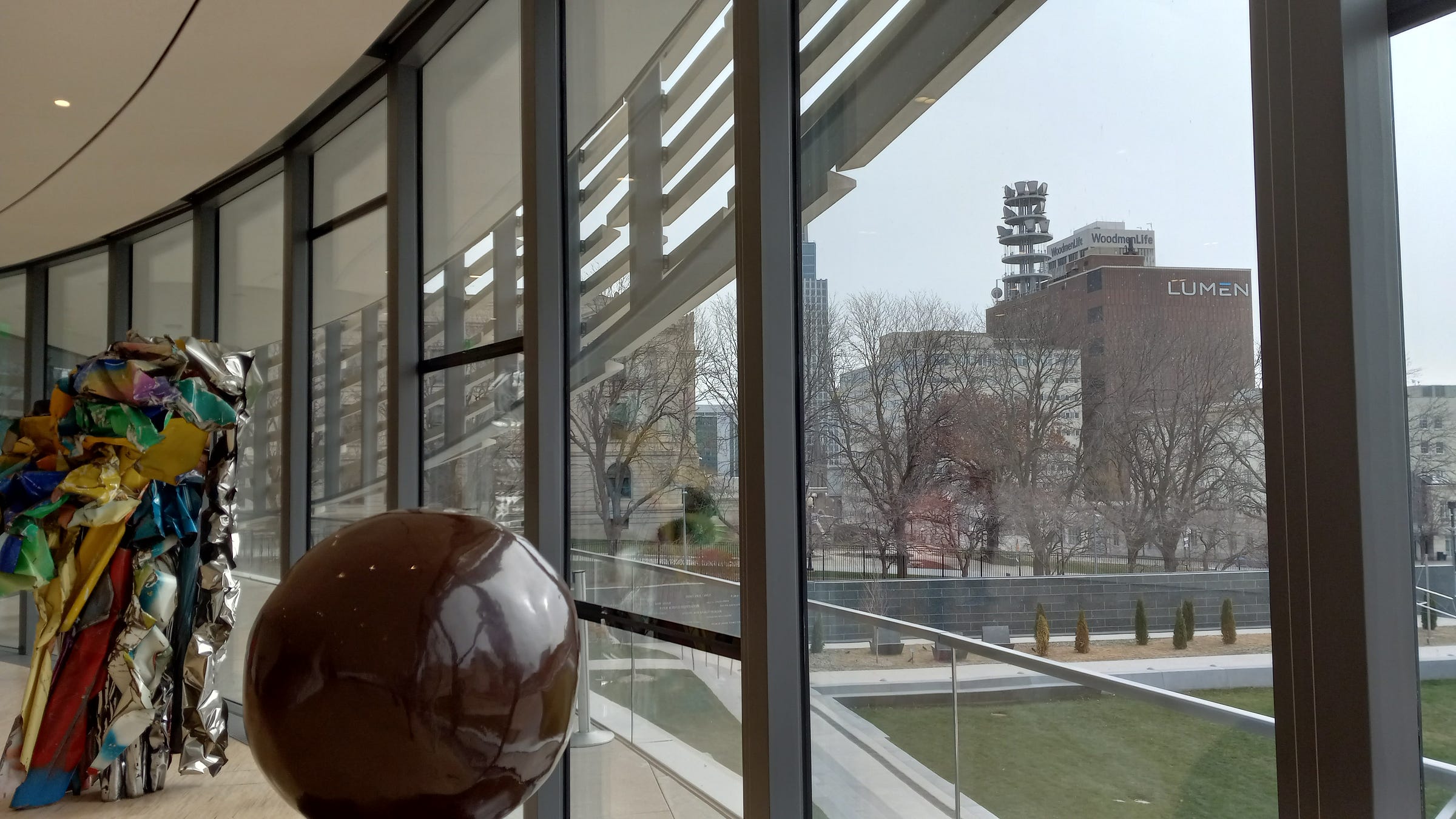

A few sculptures round out the Schrager collection. They are situated on the balcony level, and now that we’ve toured the galleries we find ourselves at the starting point again, overlooking the entrance. This looped structure provides a strange sense of closure or accomplishment which I don’t enjoy; it seems to communicate that I am done, that I don’t have to go in there again, that I don’t need to encounter the art or even think about it more than I already have. Looking out the large window overlooking the Omaha skyline, I realize that the antenna tower atop the Lumen building is just as aesthetically interesting as the sculptures in the museum.

At this point it is possible to walk out of the museum and onto a sort of rampart or balcony, which gives a spectacular view of the museum’s original entrance, built in 1931 and used until the museum’s first addition opened in 1994.2

What a contrast between this entrance and the present one! Previous generations of museum goers would have been conscious of a physical ascent mirroring a psychological or even a spiritual ascent to the columned portico of this, a temple to the great works of man. I can only imagine what the experience of looking at the artworks would have been after ascending that grand stairway. In contrast, the current entry, reminiscent of almost every other information desk we’ve ever seen, seems to do a better job of incorporating the subsequent art into our average everyday lives. Is this a good thing or a bad thing? Should art be seen as a repository of aspirational values, or as something encountered in the everyday? Which one of those attitudes is better for the art? For its viewers?

The glass sculpture we saw earlier is visible from this point as well; it beckons us to explore the rest of the museum. The galleries to the right of the curved stair contain the museum’s collection of twentieth-century abstract works. This is frankly boring to me; we just went through whole galleries of contemporary art which looks mostly the same as this. All of this is presented in a perfunctory, this-is-an-example-of-that kind of way; it strikes me that fully two-thirds of the museum’s space has been devoted to the art of the last eighty years of human history and although I feel as though I’ve become acquainted with quite a lot of different kinds of art I’m not sure if I know what I’m supposed to do with my new knowledge. I think about all this while I’m walking down a long, straight, empty gray granite passage that overlooks the museum’s old atrium and café. I like this: this space to think, to ponder and reflect. Ahead is the way back to all the galleries I’ve seen so far. To the right is the former north façade of the original museum building. Café sounds and people talking waft up to my ears. A sense of anticipation grows.

This is what counts, for all intents and purposes, as the main entrance to the old building. It is profoundly perplexing to me. An informative card tells me that the inscription refers to the benighted attitudes of the conquistadores and friars who subjugated the old lands and people of the American continent. This is the first time so far that I’ve felt a dissonance between the museum’s own attitude toward itself, and its situation in Omaha. This part of America was never visited by the Spaniards depicted in the medallions on this doorway—the first white people to come here trickled in gradually, first as hunters and trappers, then as explorers, and finally as settlers and entrepreneurs. So what are these representatives of the Spanish empire doing here? In our current cultural moment I’m not at all surprised that the museum’s curators have taken the chance to decry the doings of the Spaniards—and even to use them as punching bags for beating up the entirety of European activity on this continent. But what were the builders of the original museum thinking in 1931, when this inscription was carved over this door?

The past is a foreign country, someone once said; upon entering this door and leaving the world of contemporary art behind I am now entering the past, and perhaps I am entering it to discover or even to redeem it—but I’m hoping that my doing so will not be denounced with the same amount of vigor as the doings of the conquistadores have been. There is nothing the museum’s current caretakers can do to eliminate the sense of disassociation between the original building and the newer wings; there is simply too much division between the two parts of the building as well as between the two kinds of art showcased within. The important question that everyone must ask themselves upon visiting the Joslyn is how they are going to approach these two kinds of art—the old-fashioned, historical, past-centric kind, and the modern, contemporary, fresh and new kind: and it is a supremely clever and enlightened touch that the museum is set up to force this question upon us.

But the whole area of the entrance to the old museum is quite confusing. A series of doorways seems to beckon, but also I seem to be descending, deeper and deeper, into the bowels of some sort of basement level. Where is the art? Finally I come to this gloomy room of interactive / informative displays representing seven distinct art movements; but are we ever going to see any art? Or is this building just an education center of some kind? There is a picture of the Virgin on a wall in this room, as if the museum curators couldn’t find any other place for it.

I make my way through a little maze of winding stairs and then, finally, I’m in the museum proper: there is the entrance to the Witherspoon concert hall,3 there is the fountain court, and there, at last, is the former main entrance.

From the former atrium the architecture does not lead me in one way or another. This is the second-biggest difference between the new gallery spaces and the old: I felt as though there was really only one way to go through the Schrager gallery and the abstraction gallery, but here I’m presented with a more stochastic methodology. The building hints at what is to come but does not shove or even nudge. From the entryway, vistas open to two galleries; but the fountain court, full of beauty, also beckons. The museum is a choose-your-own-adventure, a garden of forking paths, a neural net.

My favorite part of the museum has always been the fountain court, with its inviting trickle, its columned arcades, its plants, its little details. It is one of the most beautiful indoor spaces in the city. Once, at a very fraught and tender moment in my teenage years, I took a girl here; what we said by the fountain meant, to me, probably more than if it had been said in some other place. And once I tried to take a different girl here but she wasn’t interested in coming, and that told me something about her.

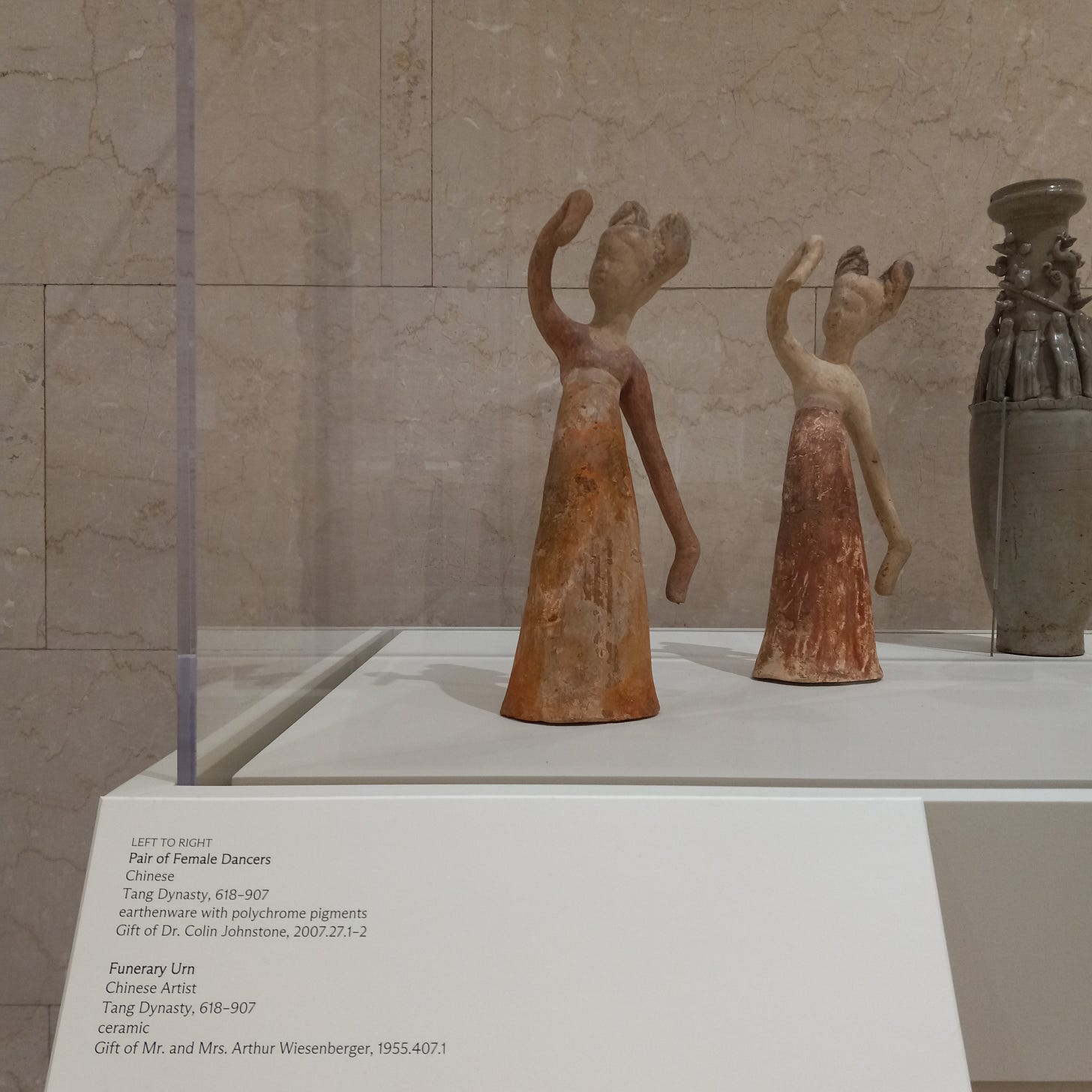

My favorite artworks in the museum are the ones installed, almost as if they were afterthoughts, in the arcades and passages surrounding the fountain court: the museum’s collection of Asian, Mediterranean, and Egyptian art. All of these craft objects are so full of beauty and skillful craftsmanship: the vases, the jars, the bits and pieces of old temples, the very tiny statue of a cicada.

There is so much to think about when pondering these craft objects. Who used them? What was it like to use them? Were they everyday objects, or were they reserved for special use, for the Japanese or Mycenaean equivalent of thanksgiving dinner? I love the tersely descriptive captions on the title cards. “Drinking cup” — “storage vessel” — “Carved strut from a temple car” — “Pair of female dancers.” The opposite of the paragraphs of explanatory text in the newer wing, they invite speculation, even wonder. Who made these dancing girls? Why did they do it?

This is the equivalent of outsider art, like that of Henry Darger—only it is we who are the outsiders, forever kept away from these objects’ true significance in their makers’ lives.

Besides the craft objects this side of the museum also contains a collection of European and American art. This section is presented as a row of galleries in a very long U-shaped line; in this sense it is linearly constructed like the more modern galleries. But paintings tended to be smaller in earlier times, and also these galleries are each quite large; so the viewer is much more able to wander at will. It annoys me that one of my favorite paintings in the museum—Daniel Huntington’s Roman Ruins in Southern Italy, which is featured as the cover artwork for this blog—is currently off display. But the crowning glory of the museum’s holdings is still visible: the collection of Native American and western art, including the records of Prince Maximillian’s journey across the prairies in 1833-34. Maximillian was accompanied by Karl Bodmer, a watercolorist who documented the landscape, wildlife, and people on the plains in stunning detail; the museum has a fine collection of his paintings, along with an array of associated objects (including Maximillan’s journal of his expedition). This part of the museum is what ties it most strongly to the Omaha community; much of this art documents the cultures which existed in this part of the world and which are now irretrievably gone. In contrast to the modern and contemporary wings in the other part of the museum — and in contrast with the beautiful Asian craft objects shown nearby—the collection of American art at The Joslyn feels like art which still speaks intelligibly to me, connecting me to a not-quite-distant time and people who lived in the same place as I do. Their lives overlap with mine in a much more immediate and tangible way than the lives of the makers of the vases and temple furnishings in the nearby hallways.

And thus we come to the conclusion of our trip to see The Joslyn. As I said earlier, some aspects of the renovation make me sad, and some, I think, are fine touches. The sharp division between “then” and “now,” between the white-cube world of contemporary art and the temple-of-humanism older wing of the museum, is an inspired feature; it’s not The Joslyn’s fault that there is such a profound break between the past and the present in the world of art, but the museum’s builders were wise to accentuate that divide.

Still, I wish the newer wing was more . . . interesting. While I was in the original wing I kept noticing little architectural details, like this air duct cover and this stair railing. Why couldn’t these kinds of details be included in the contemporary galleries? I saw nothing of such obvious beauty in the furnishings of the museum’s newer wings.

The inclusion of these details subtly hints to me that for all the faults of the old style of museum culture, with its idea of the Canon of Great Works and all the associated cultural baggage that goes with that idea, there was still an awareness that art is not just the stuff in frames on the wall; art could extend to even the tiniest details of regular life, to the stair rails and the furnace ducts. But what does the contemporary wing tell us? Gone are any hints of beauty in the furnishings of the newer gallery, unless you count the beauty of the grand architectural gesture—the curving stair, the exposed steel beams. Is beauty only something that trained professionals can ever do? The art on the walls in the Schrager gallery: let’s be honest with ourselves and admit that none of it was beautiful. Thought-provoking, yes; even pleasant at times—but never beautiful in the same sense as the works of the Old Masters or even the Impressionists. Modern art is fleeing any association with the concept of the beautiful in favor of the self-expressive, the innovative, and similar concepts. And contemporary, non-beautiful art gets put up on the museum wall almost as soon as it gets made. For the average person who just wants to go to a museum to see the best pretty pictures ever made, or for the aspiring art student who is trying to figure out how to launch their career, I’m afraid museums such as The Joslyn are proclaiming a very clear message that beauty doesn’t matter anymore.

I hope I’m wrong.

It is likely that the David has transcended that category—its reputation is unimpeachable and therefore it can be parodied (and parody is itself a kind of warped reverence).

Well, technically, it’s still being used as an entrance. But when I went there it did not appear as if I was expected to use it. Much of the grand doorway (split into three parts, like a cathedral door) was boarded up with plywood. I was able to get in, but the girl at the counter who gave me my metal pin did not seem as though she thought anyone at all was going to come through that door. She took my zip code by writing it down on a sticky note because her computer wasn’t booted up.

Actually, now that I think of it, it would be possible to go in the museum via the old entrance and have a completely different experience of the museum than if you used the new entrance. You wouldn’t even have to enter the modern / contemporary galleries at all if you didn’t want to, yet you would still have a completely satisfying museum experience. This is a very intriguing possibility for me.

Originally the museum was meant to showcase performance art as well as visual art; the concert hall is still used, but not as much as was originally intended.

My husband and I visited the 'new" Joslyn last December. I must say, I am not a fan of the contemporary art collection. Just not my scene.

But, I love the older stuff. And even my Parisian husband was impressed by the architecture and the art collection.

Enjoyed this.

A relevant book, if you haven't read it, would be Inside the White Cube by Brian O'Doherty.