The Painted Word (Tom Wolfe, 1975)

Ah, Tom Wolfe, Tom Wolfe—you alien! You man from Mars!1 You who exist so far outside the circles of thought and practice which you so delightfully describe—no wonder your views are vilified and dismissed! In the 1960s, Tom Wolfe made a name for himself by looking into the nooks and crannies of popular culture, the strange and wild stuff on the fringes, and writing about what he saw with some of the most memorable prose of the twentieth century. He cultivated a stance at once intimately involved and intellectually distanced; as time went on he shifted his focus from the weirdos of the sixties to the phonies of the seventies in the pages of New York magazine. In 1975, he focused his attention on the world of contemporary art—the result was his devastating and absolutely hilarious little book, The Painted Word.

Wolfe’s main complaint in The Painted Word is that what paintings actually look like has become subservient to the theories behind the art, the isms to which the artists subscribe. He traces the history of the modernist sensibility in American art from its first appearance in the twenties up to his current time, which was, in 1975, the height of such movements as minimalism and conceptual art. Gordon Matta-Clark, Sol LeWitt, and Bridget Riley were big names during this period; critics such as Clement Greenberg and Leo Steinberg had been propounding new theories to explain the art—abstract expressionism, pop art, conceptualism—or was it the other way around? Were the paintings made to match the theories? Without the critical-theoretical apparatus, would the paintings have been able to stand on their own merits? Wolfe looks very dubiously on this arrangement.

All these years, along with countless kindred souls, I had made my way into the galleries of Upper Madison and Lower Soho and the Art Gildo Midway of Fifty-seventh Street, and into the museums, into the Modern, the Whitney, and the Guggenheim, the Bastard Bauhaus, the New Brutalist, and the Fountainhead Baroque, into the lowliest storefront churches and grandest Robber Baronial temples of Modernism. All these years I, like so many others, had stood in front of a thousand, two thousand, God-knows-how-many thousand Pollocks, de Koonings, Newmans, Nolands, Rothkos, Rauschenbergs, Judds, Johnses, Olitskis, Louises, Stills, Franz Klines, Frankenthalers, Kellys, and Frank Stellas, now squinting, now popping the eye sockets open, now drawing back, now moving closer—waiting, waiting, forever waiting for . . . it . . . for it to come into focus, namely, the visual reward (for so much effort) which must be there, which everyone knew to be there—waiting for something to radiate directly from the paintings on these invariably pure white walls, in this room, in this moment, into my own optic chiasma. All these years, in short, I had assumed that in art, if nowhere else, seeing is believing. Well—how very shortsighted! I had gotten it backward all along. Not “seeing is believing,” you ninny, but “believing is seeing,” for Modern Art has become completely literary: the paintings and other works exist only to illustrate the text.

The text, of course, being the theories of the critics. The extremely insular and chummy art scenesters at the time (only a few thousand people, whom Wolfe calls “Cultureburg”) were not looking to their own tastes and likes, but to Greenberg et al. to declare to them what art was good and what wasn’t. Wolfe heaps a great amount of scorn on this system of critical pronouncements → new theories → art to match, such as in this passage describing the career of Morris Louis, the founder of the Washington Color Field School:

A forty-one-year-old Washington, D.C., artist named Morris Louis came to New York in 1953 to try to get a line on what was going on in this new wave, and he had some long talks with Greenberg, and the whole experience changed his life. He went back to Washington and began thinking. Flatness, the man had said . . . (You bet he had) . . . The spark flew, and Louis saw the future with great clarity. The very use of thick oil paint itself had been a violation of the integrity of the picture plane, all these years . . . But of course! Even in the hands of Picasso, ordinary paint was likely to build up as much as a millimeter or two above mean canvas level! And as for the new Picasso—i.e., Pollock—get out a ruler!

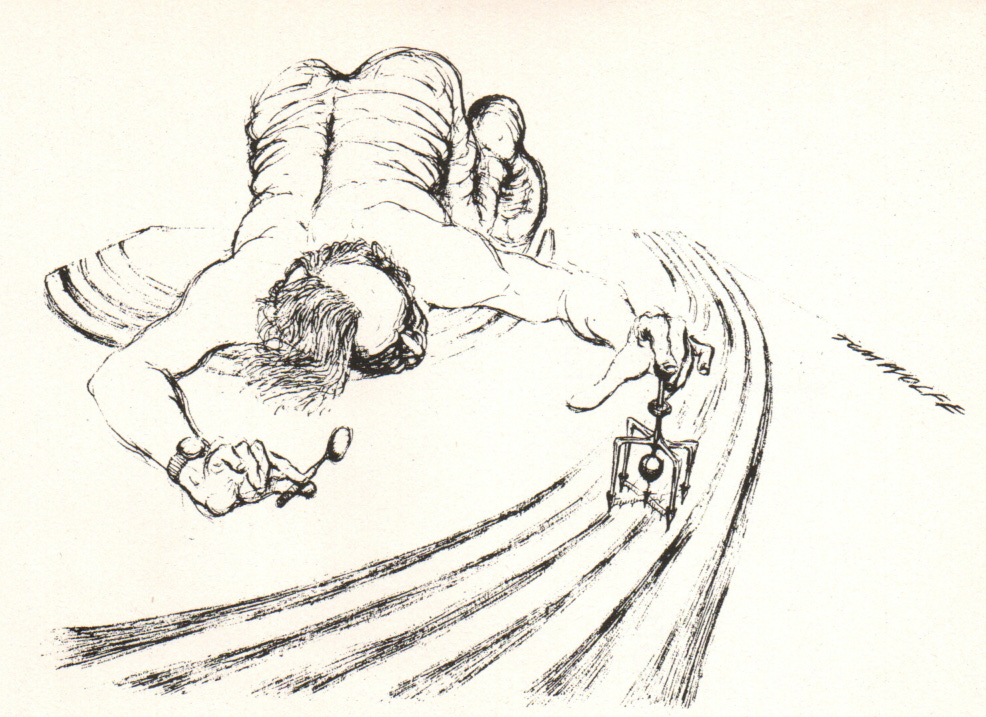

So Louis used unprimed canvas and thinned out his paint until it soaked right into the canvas when he brushed it on. He could put a painting on the floor and lie on top of the canvas and cock his eye sideways like a robin and look along the surface of the canvas—and he had done it! Nothing existed above or below the picture plane, except for a few ultramicroscopic wisps of cotton fray, and what reasonable person could count that against him . . . No, everything now existed precisely in the picture plane and nowhere else. The paint was the picture plane, and the picture plane was the paint. Did I hear the word flat?—well, try to out-flat this, you young Gotham rascals! Thus was born an offshoot of Abstract Expressionism known as the Washington School. A man from Mars, incidentally, would have looked at a Morris Louis painting and seen rows of rather watery-looking stripes.

Wolfe depicts Louis in a deliberately unflattering light here; if Louis seems to come off as a dupe of the critics, it’s because Wolfe has nothing but scorn for Greenberg and the other theorizers. He sees them as only self-serving, jockeying for status, influence, and the bragging rights which come to the discoverer of the newest school:

Meanwhile, Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg made a grave tactical error. They simply denounced pop art. That was a gigantic blunder. Greenberg, above all, as the man who came up with the peerless modern line, “All profoundly original work looks ugly at first,” should have realized that in an age of avant-gardism no critic can stop a new style by meeting it head-on. To be against what is new is not to be modern. Not to be modern is to write yourself out of the scene. Not to be in the scene is to be nowhere. No, in an age of avant-gardism the only possible strategy to counter a new style which you detest is to leapfrog it. You abandon your old position and your old artists, leaping over the new style, land beyond it, point back to it, and say: “Oh, that’s nothing. I’ve found something newer and better . . . way out here.” This would dawn on Greenberg later.

Of course, when the book came out, the art world cried foul. Accusations and denunciations were everywhere; one reviewer called the book “a moustache painted on the Mona Lisa,” one said it was “a philistine utterance,” and another called him “A six-year-old at a pornographic movie; he can follow the action of the bodies but he can’t comprehend the nuances.” The biggest critique was that Wolfe was not part of the art world and therefore couldn’t possibly know what he was writing about. It was all art-world insiders who said these things, though; as Wolfe himself said about his critics, “Intellectuals aren’t used to being written about. When they aren’t taken seriously and become part of the human comedy, they have a tendency to squeal like weenies over an open fire.”2

However, it’s easy to criticize Tom Wolfe’s methods. He mocks the avant-garde artists for their tendency to always move to New York to jumpstart their careers—but isn’t that what Wolfe himself did, when he left his job as the Cuba correspondent for the Washington Post and moved to New York in 1962? He complains about theory being of more importance than substance—but he himself expended much energy explaining and theorizing about his own writerly style in The New Journalism and “Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast.” More to the point, when he gets annoyed at paintings which are all about theory or merely illustrations of texts, he forgets that paintings have been primarily illustrations of literary texts for the last several hundred years. All those Old Master pictures of Biblical subjects are incomprehensible if you don’t know the Scripture passage that goes with the painting, and the allegorical-mythological paintings on Greek and Roman subjects are even worse.

Wolfe never suggests a way forward; he never breaks character as a journalist, never reveals what his own feelings are on the matter, never says what kind of paintings he himself likes. Consequently, there is a little whiff of nihilism around his gleeful pointing and laughing at the whole critical-artistic apparatus as it existed in the sixties and seventies; but what Wolfe was really doing was culture care, even if it seems as if he is tearing down instead of building up. He is clearing the ground so that something else can be grown there, even if he is not the one doing the planting. And if Wolfe’s methods might seem brash, it’s because he is simply carrying on the tradition of high, pointed literary satire which stretches back from himself to Jonathan Swift (“A Modest Proposal”); Martin Luther (The Bondage of the Will); the Greek satirists, especially Menippus of Gadara; and even all the way back to the prophets Isaiah and Elijah, who mocked and ridiculed the Israelites who chose to worship false idols instead of the revealed God.3

The Painted Word ends with an envoi discussing the reception of the works of the photorealists, painters who rejected the tenets of the abstract expressionists and painted scenes of contemporary realism. Painters such as Richard Estes and John Baeder would blow up a photograph and then copy it in exacting detail onto the canvas; “One of the things they manage to accomplish in this way,” says Wolfe, “is to drive the orthodox critics bananas.”

Such denunciations! “Return to philistinism” . . . “triumph of mediocrity” . . . “a visual soap opera” . . . “The kind of academic realism Estes practices might well have won him a plaque from the national Academy of Design in 1890” . . . “incredibly dead paintings” . . . “rat-trap compositional formulas” . . . “its subject matter has been taken out of its social context and neutered” . . . “it subjects art itself to ignominy” . . . all quotes taken from reviews of Estes’ show in New York last year. Photo-realism, indeed! One can almost hear Clement Greenberg mumbling in his sleep: “All profoundly original art looks ugly at first . . . but there is ugly and there is ugly!” . . . Leo Steinberg awakes with a start in the dark of night: “Applaud the destruction of values we cherish! But surely—not this!” And Harold Rosenberg has a dream in which the chairman of the Museum board of directors says: “Modernism is finished! Call the cops!” Somehow a style to which they have given no support at all (“lacks a persuasive theory”) is selling.

What a topsy-turvy situation! Again, Wolfe, being a journalist, is very careful to not display his own feelings on the subjects he writes about, but I can’t help but wonder what he thought of the whole thing. In a few later essays (most notably “The Invisible Artist” from Hooking Up) he seems to indicate that he himself puts a high value on skill and craft in art, at the expense of content or message. But these moments of self-disclosure are rare in Wolfe’s works, and absent entirely in The Painted Word.

So . . . how are things coming along today? Has the art world moved beyond the hangups that Wolfe discussed? What’s going on these days in Cultureburg? It is, of course, impossible to tell, at the current moment, who will be talked about in fifty years’ time, just as it was impossible to tell, in 1943, that Jackson Pollock was going to be big stuff in the years ahead. But a big difference I’ve noticed is that the avant-garde has embraced the social consciousness that Wolfe notes as being specifically not part of the sixties / seventies avant-garde toolkit. He mentions that in the thirties there was a short burst of conscious art coming out of the avant-garde. But that got chased out by the theorizing of the critics in the forties and would not be seen again until our contemporary moment. Another difference: I get a definite feeling that the contemporary art world is even more insular and defensive than it was when Tom Wolfe peeked into it. These days, it feels like the bottom has been hollowed out of the avant-garde; for students fresh out of school, the making of an artist statement and the crafting of a theory seem so . . . formulaic. The avant-garde has swallowed the academy and adopted its methods. Things like video installations and site-specific performance pieces are being taught with the same mannerisms that Gérôme and the academics were using in the 1870s, before impressionism got big.

And who are the top critics now? Where is this generation’s Clement Greenberg? It doesn’t appear that there are really any critics at this time who enjoy as high a profile as Greenberg had, but that almost seems to be because the function of a Greenberg-esque critical voice, one who is actively championing new styles, has been delegated to the most prominent collectors and dealers such as Charles Saatchi and Larry Gagosian. This trend has been extensively chronicled in Don Thompson’s excellent book The $12 Million Stuffed Shark; as it is, it really does feel like there isn’t much remaining of the intellectual, theory-driven side of art critique and practice, and we are left only with the hoary old dictum of the avant-gardists of the nineteenth century, the command that art should, above all else, shock the bourgeoisie. Yet the big collectors just keep buying it all up. Does the art-loving public really love art? Or do they merely love the status, or the investment value, that art brings with it?

If that last question must be answered with a “yes,” then I fear we are in a new emperor’s-got-no-clothes situation, similar yet distinct from what Tom Wolfe chronicled in The Painted Word. Either way, I find it supremely ironic that all these avant-garde styles seem to slide into a tame kind of domesticity after a while; I’ve seen plenty of pseudo-Rothkos and quasi-Klines on the walls of doctor’s offices, hotel lobbies, and chain coffee outlets. For all the lofty philosophizing of the theoretician-critics, the fate of even the most fiercely confrontational artists of the mid-twentieth century tends toward becoming material for interior decorators. I’m certain Tom Wolfe would find that worth a good laugh.

As reported in The Sydney Morning Herald, December 18, 2004:

It's hard to imagine Wolfe blending in with the crowd, but that's never been his strategy. Wolfe began wearing the white suit in 1962 and continued because it provided a helpful barrier between himself and his subjects. “It made me a man from Mars,” Wolfe says, “the man who didn't know anything and was eager to know.”

Richmond Times-Dispatch, August 17, 1975.

Great write-up about Tom Wolfe’s take on modern art. It’s funny how much our appreciation is guided by reaction and impulses that tend to settle and soften over time—hence the reason we see modern art in doctor’s offices and think nothing of it. It’s hard to imagine that book being published today, yet in its day it was a daring statement.