Unscheduled off-topic brain dump about localism: a pseudo-manifesto

1

This extra edition of RUINS addresses an idea that I’ve seen popping up with increasing frequency and force in the last few months: that the social internet, as we know it, is dead. There is some hyperbole inherent in that statement, of course, but the word “dead” is the broadest net I can find to catch all the multiple strands of thought encompassed by the idea. The internet is boring; the internet is a distraction from reality; the internet is superfluous; the internet is harmful; the internet is blasé; and so on. Rather than worry over a precise definition of the idea, though, I will bring to your attention some essays which have appeared recently and let you note the connections between them, the overlaps, the gestalt. These are just a few of the essays I’ve read recently which address this idea; there are more, but these are the best ones.

Rachel Haywire, Offline is the New Online

Nathan Woods, We Have to Make Phones Lame

Thomas J Bevan, The End of the Extremely Online Era

Danny Anderson, Deleting Myself (For Now) From Social Media

See a pattern here? The people with their finger on the pulse are leaving the social net and openly predicting its imminent collapse. Rachel Haywire gives it four years tops before less than fifteen percent of the population will be using the old social sites; she sees a future of salons and backchannels like Discord rising as the legacy giants crumble apart. Danny Anderson and Katy Carl are quitting, just like that, because they’re sick and tired of the manipulation experienced on these platforms. Bevan and Woods predict that internet usage will rapidly lose its luster and that only the very uncool will allow themselves to be seen in public using their devices—Woods has even poked his ears into the future and has come back, like a prophet, with snippets of the kind of dialogue he heard: “Psh. Did you see Josh at lunch, thinking he’s slick and checking notifications under the table?” “Yeah, what a phonecel.” “Total doomscroller. Take him off the invite list for this Saturday.”

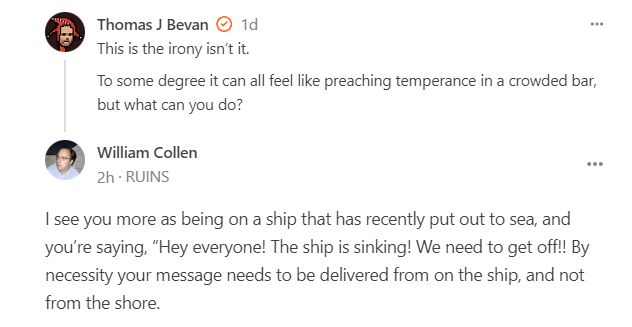

I’m aware of the irony of talking on the internet about how the internet is dead. Yes, yes, the haters can jump all over the above essayists and say that the authors are being duplicitous, or worse, that they are simply indulging in a craven grab for clout or virality. More sympathetic readers are concerned that, if we were to have followed this advice, we would not have ever encountered the advice in the first place. But I don’t see it like that. This is what I told Thomas Bevan regarding the irony:

These conversations will always have a whiff of catch-22-ism about them; but that’s not the fault of the conversations or those involved in them—it’s simply a reflection of how pervasively the internet has colonized our discourse. It is indeed true that, without the internet, we would not have encountered these authors. But the internet wasn’t necessary to get authors in front of readers until only, at most, two decades ago . . . and we could go back to that time if we really wanted to. But it will take a lot of work. I’m disturbed by the voices I’ve heard who predict that it will be impossible to return to the days when the social net didn’t matter—here is Ray Downs arguing that, since people work from home so much now, the social internet will colonize their entire lives:

This means people will be physically alone for much of their day. And what do people do when they’re alone? They go online. They scroll. They entertain themselves with funny videos, music, and this Substack. They live their digital life, which is sometimes more visceral and meaningful than their physical one.

Yes, that is indeed what people are doing when faced with the loneliness of working from home; but Downs seems to be mistaking this is what we are doing right now with this is what we could be doing. (Also, surely the work-from-home people aren’t working 24 / 7? Surely they can interact with the physical world after their workday is done?) Like I said earlier, we could disengage with the social internet . . . if we really wanted to. To do so will require a deliberate cultivation of an older sense of how to engage with ideas. We will need to prioritize reading and thinking slowly. We will need to resist the urge to share every little thing that pops up in our consciousness; we will need to determine if what we see is even worth sharing at all, is even worth responding to in any way. We will need to give up on our desire to come into intimate contact with the writers we admire. And we will need to be ready to invest much more heavily in discourse forms which favor the local over the global.

2

A few months ago, after I published my thoughts on listening to music in the Spotify era, Kevin LaTorre issued this command.

It’s true that there are hints of localism and place-centric community scattered throughout my writing; but I don’t know if I have it in me to write a manifesto in the old, high style, the kind of manifestos that the artistic avant-garde have been cranking out for the past twelve decades or so. What I have instead is a set of principles which can be used by anyone seeking to implement the kind of internet-is-dead philosophy expounded in the above essays.

The most insightful, prescient piece of social commentary ever written in America was Henry David Thoreau’s line from Walden about the telegraph.

We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas; but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate. We are eager to tunnel under the Atlantic and bring the old world some weeks nearer to the new; but perchance the first news that will leak through into the broad flapping American ear will be that Princess Adelaide has the whooping cough.

Well . . . it’s happening. People are finally realizing that they don’t really care about Princess Adelaide’s whooping cough, or what kind of sauce Taylor Swift was dipping her chicken strips into, or all the other little things that the internet loves to push in front of our faces. But if Maine and Texas aren’t communicating anything to each other, what are they to talk about, and with whom?

Maine will talk to Maine about Maine, and Texas will talk to Texas about Texas. It’s that simple. Once we get over our silly desire to have up-to-the-moment updates on all the things that don’t affect our lives and that we can’t do anything about anyway, we will realize that the world immediately in front of us—our city, our backyard, our neighbors—is quite impeccably worth our attention.

On that great day

the server farms will burn

and all our internets will fall away

and we will finally hear our thoughts

and be confronted with the world around us.

Then we will see that all the people next to us

were good enough the whole time.

So: get ready for the copious unfolding of the new localism, in every aspect of our lives and in every intellectual discipline. Take art criticism, for example: we won’t talk so much about the stuff that is happening in art capitals such as New York or London; instead we will devote substantial amounts of time and energy reporting on what’s happening at our hometown galleries.1 We will engage with art that has its home where we are—art which has an ability to communicate to us in ways that simply aren’t available for art that we only see from reproductions in books or read about online. We will prioritize the supporting and encouragement of local talent; we will offer financial incentives for artists to stay in our hometowns, which will facilitate closer and more personal relationships with local artists, which will cause us to develop greater empathy, humility, and respect—qualities which are often lacking in the current critical scene. What’s not to like in such a program?

But if, in this pseudo-manifesto, I may make one definite and specific demand, it would be for LOCAL MEETUPS. Nathan touched upon this subject in his “Make Phones Lame” essay above, advocating for poets as throwers of dinner parties at which poetry is read. I applaud this suggestion; but there are many more ways a renewed localism could manifest itself in meetups. Dinner parties; reading clubs; picnics;2 close colloquys by a slowly-dying fire;3 lazy afternoons of slowly-unfurling chat4—all of these methods are worth studying and deploying. And I’d like to hint that, until we see the full development of local communities with shared intellectual interests, there is nothing wrong with a journey of a few hours, or even a few days, for the purpose of meeting for a long talk with a friend who had previously existed only as part of the ever-shrinking, increasingly-irrelevant online scene. It is time to make the kinds of long pilgrimages with which the old novels abound. Jane Bennet staying for the season with her aunt and uncle in London, and Anne Shirley and Diana Barry staying with Diana’s great-aunt in Charlottetown, ought to be our models going forward.

3

But if you don’t want to partake any longer of the rapidly-decaying landscape of social media, and you don’t have a readily available group of local friends with whom you can discuss the serious stuff, where are you to turn for connection on an intellectual level? The answer has been with us all the while: magazines. There is something undeniably special about getting a magazine in the mail; and a well-crafted magazine with a robust editorial stance is one of the best ways to engage in the discourse in a way that preserves the autonomy of the reader, rather than playing games with the readers’ attention and emotions as too often happens on the social net.

In mid-November I will be going to San Antonio to visit an event held by the team at Plough magazine, about how small presses and magazines can serve as a vital link in our societal landscape.5 The interesting thing about magazines is they don’t have to be a big production; the heritage and history of small presses indicates a wide latitude in form and format. Dostoevsky wrote and published The Diary of a Writer entirely by himself. Addison and Steele distributed The Spectator to subscribing coffeehouses, where each copy would be read by thousands of readers. Paul Williams’ Crawdaddy started out as a fanzine mimeographed by hand by Williams’ friend Ted White. Charles Bukowski published some of his poems in Gallows, a magazine which only printed two issues. Anyone is able to cobble together some writing, by themselves or their friends, print it out in chapbook or zine form, and go around town dropping it off at coffee shops and other sympathetic places.

A few days ago I went on a quick grocery store run and saw a beautiful and still-too-rare sight in the parking lot: four kids, maybe sixteen years old if I could guess, were gathered together. They had a box of doughnuts, and they were just eating doughnuts and talking. No phones in sight—just enjoying each other’s company.

This is my vision of the new, localized, net-dismissive culture. People hanging out, being in relationship with each other. Talking about whatever. Maybe they were making plans for a new micro-press zine or something like that; maybe they were talking about school stuff, or movies, or books—or maybe it was Doughnut Club Night and the new creme filleds had just come out of the fryer. I don’t know! But they sure were having a good time, in glorious propinquity, and with no devices in sight!

Literary example: Chernyshevsky, What Is To Be Done?, chapter 3, part 6.

Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring, chapter 2, “The Shadow of the Past.”

Wells, Tono-Bungay, chapter 4, part 3.

And if any RUINS readers would like to meet together on the 17th, I’ll be in San Antonio all day!

A noun for your localist principles, as they develop for aesthetics and culture: neighborliness.

The realization that screen worlds can be deleterious to well-being has a long history. Christians have been wary of the theatre as a simulacrum delighting the eyes in a way similar to Eve's eye-rationale in Genesis 3:6. In my childhood it took the form of being told to go outside and get some exercise rather than watching TV. In the very earliest days of the Internet (before the www), Cliff Stoll, an expert on virtual realms removed himself from them entirely after epic immersion hunting hackers. He wrote about why in "The Cuckoo's Egg".

I think also of the various Silicon-Valley tech gurus who don't/didn't let their kids have smartphones. And that brings up artistic depictions of the danger of virtual worlds (screens in particular) in films like 2001: A Space Odyssey. (Kubrick may have had his own private reasons to warn and confess his culpability in creating virtual illusions... e.g., in The Shining, but we'll leave that rabbit-hole to another thread!)

Lastly (and my mind is still reeling from this one), the book "American Cosmic," by D.W. Pasulka contains some mind-blowing nuggets about how dark spiritual forces seem to love leading us by the eyes. One big idea among many: some of the founders of the Internet, back at SRI, in the 1970s were also involved in dark government experiments into remote viewing... which is basically demonic. Now, think about the Internet (and especially video on it, live or recorded) and let that thought sit for a bit. As for me and my house, it's a paper Bible every morning to get my head screwed on straight before I reach out to "places" like this!