Varieties of artistic toil

Note: A heartfelt thanks to the new readers who joined me this week; there seems to be quite a lot more of you this morning than is usual, but you are all welcome. If you haven’t yet done so, feel free to take a tour through this list of what I consider some of my best writing. Thank you!

1.

Pictured above: Albrecht Dürer’s watercolor of a rabbit from 1502, a masterpiece of observation. in many of his paintings and graphic works Dürer displays a near-omniscient power of noticing; in this one he has captured every imaginable nuance of light and shade, of texture and sheen, of the creature’s body. The fur is painted with the most exquisite detail, every hair reproduced. Each individual whisker is drawn. The folds of the rabbit’s skin on the back of its neck are astonishingly realistic. Dürer painted other pictures of animals—a bird’s wing, a deer’s head—but this one has something special about it: a dead bird’s wing can be labored over indefinitely, but this rabbit seems so alive—how did Dürer persuade the famously timid animal to sit for its portrait? Or was Dürer’s observational skill such that he could create this painting after only a quick glance before the creature hopped nervously away?

Whatever the case, the picture is remarkable for the amount of toil it evidences. Hundreds and hundreds of brushstrokes were needed for all those little hairs. Dürer would have had to log many hours of practice in the medium of watercolor before he could know how to finely balance the darks and lights he achieved in this notoriously tricky medium. And how much hand-eye coordination is required to paint, not just the whiskers, but the highlights along the top of those whiskers? Masters like Dürer make the hard work look easy, but the hours of hard work, the endless practicing, the student exercises and false starts, were all a necessity before Dürer could become a master. The reward is here in this painting: Dürer proves, here, beyond a doubt, that he was a master dedicated to the ways of the craft and unafraid of spending hours perfecting his skill.

There are many other examples of this kind of patient toil in art. Think of the elaborate inlaid tile floors of paintings such as Jan van Eyck’s Madonna, St Michael, and Catherine, or the painstakingly-reproduced patterns in Ingres’ portrait of Madame Moitessier. These examples could be multiplied many times over throughout the history of art, and not just in paintings, either. Imagine the patient care it would have taken to chip away at a block of marble, or to carve the ornate stonework on the facades of medieval cathedrals: one slip of the chisel and the work could be destroyed.

More than anything, these examples serve as instances of just how willing the great artists are to undergo tedious, repetitive, finger-cramping work—toil—in the service of their craft. In some of these examples, such as the stonework of a cathedral, there was a higher purpose to justify the toil. But often it seems that the artists engaged in toilsome labor simply for the joy of it. There’s no reason why Ingres had to paint such a complicated floral pattern all over Madame Moitesseir’s dress, no reason why Van Eyck’s Madonna had to be seated on an ornate parquet floor—other than to showcase the painter’s skills. And Dürer’s rabbit? There is no evidence that he painted it for any other reason than his own personal enjoyment. These artworks indicate that for the artist there can be joy in toil—else why do it? It can be easy to forget this kind of joy in the present day, when it seems that many of the most celebrated artists of the last century rarely exhibited a willingness to toil at their art. The works of painters such as Pollock, Rothko, Barnett Newman, or De Kooning—not to mention the conceptual art of such people as Damien Hirst or Sol Lewitt—make it seem as though toil is unnecessary. And when anyone can get an AI image generator to produce a picture to their specifications within moments, what is the reason for investing hundreds of hours perfecting a skill?

Of course, the question can be asked of any type or kind of human work. Why do it? Is there a value inherent in labor, in toil, beyond its immediate productive results? For me these are rhetorical questions; I’m reminded that work was given to Adam and Eve before they brought the curse of sin into the world. Therefore I would hope that anyone pondering an artistic career would not hesitate to embrace the patience, discipline, and toil which have characterized the arts throughout the ages.

2.

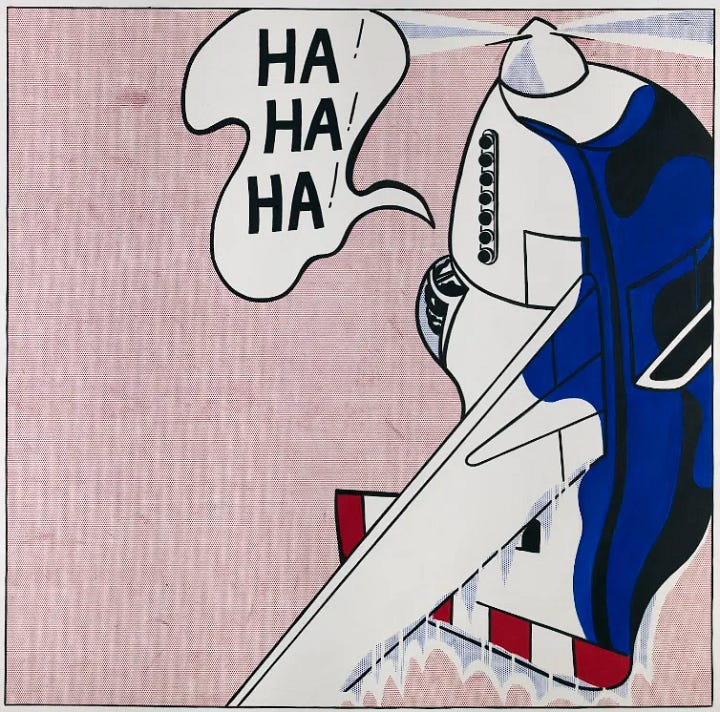

But are some kinds of toil just too much? Surely there are some aspects of labor—the dangerous or the mind-numbing—which aren’t worth being done by humans and which can be offloaded to machines. The history of art is full of this kind of toil, too; hence artists have invented rulers, French curves, mahlsticks, and other tools to help them steady their hands and make the work of drawing a little easier. Certainly an artist could work on perfecting their muscle control and eye-hand coordination to the point of not needing compasses or rulers, but with such simple and efficient tolls at hand, why bother? Roy Lichtenstein’s art contains a particularly striking instance of an artist’s use of a tool.

Lichtenstein’s paintings present an interesting challenge to the viewer who sees them reproduced in books. At the size of an average printed illustration they look almost exactly like the comic book panels the artist was copying; little to no trace of the painterly hand is in evidence. If you stare hard enough at the printed reproduction you will notice some of the colors are made of patterns of evenly spaced dots. This might seem to be a product of the printing process; the effect is called Ben Day dots as commonly employed in the mass market romance comics of the middle of the twentieth century. Most art books don’t use such a cheap printing technique as that because the quality of the illustration suffers when Ben Day dots are used, and they will instead employ the halftone process for color reproduction of artworks. The truth about the dots in Roy Lichtenstein’s paintings is that he painted them by hand, deliberately.

His method, though, changed over time. His first painting with fields of dots in it is Look, Mickey! from 1961; I am not aware how he made the dots in that one—it is possible that he painted them one at a time by hand, but I’m not sure. In his next painting, Popeye, he dragged a lightly-laden brush across the canvas, allowing the texture of the canvas itself to create a dot-like effect; this, however, he found unsatisfactory. His solution was to get a small piece of sheet aluminum measuring two by sixteen inches and drill holes into it, using graph paper as a guide to the placement of the holes. He could then lay the resulting stencil over his canvas and push paint through the holes with a toothbrush. The effect can be seen in several of his paintings from 1961, such as Engagement Ring:

Engagement Ring was one of the paintings shown in Lichtenstein’s first solo show, the famous one at the Gagosian gallery which sold out even before it opened; but Lichtenstein himself wasn’t happy with the kind of dots he was getting from his homemade setup. As you can see in the above images, he had alignment problems every time he had to move the piece of aluminum to continue the dot pattern; also, it seems he wasn’t precisely accurate in the drilling of his holes—they aren’t spaced exactly evenly apart. So he tried something else: a large metal screen with mechanically-produced and precisely-spaced rows of holes, which he sourced from an industrial supply company.1 The result looks almost exactly like the Ben Day dots found in the comic books from which he was plagiarizing his imagery.

Although Lichtenstein stated that his goal was to remove every trace of his own painterly activity from the finished work, signs of his labor still persist: here is a super-zoomed-in view of a typical artwork of his from the seventies—Still Life with Red Wine—showing his pencil sketch and how the paint, squeezed through the holes in his metal grid, seeped underneath the metal:

So the question is: was Lichtenstein being lazy in not learning how to draw all those dots with a brush one by one? This has important implications for the use of AI image generators in artistic practice. How far ought an artist go in the effort to ease their own workload? Is it a betrayal of the muse to type out a text prompt and let the machine do the rest? What about using stencils to make rows of dots? Rulers and compasses to make lines and curves? Apprentices to paint the skies and clouds? Ought a real artist grind their own paints, weave their own canvas, etc., etc., etc.? Where is the line to be drawn? Obviously the answer is up to each individual artist. And notice how I totally dodged the question, earlier, when I asked if there was a value inherent in artistic toil beyond the immediate results. That question is also up to the artist to answer.

I do think, though, that if Albrecht Dürer had used some sort of mechanical device to draw his rabbit—some sort of special brush, maybe, which could lay down dozens of rabbit-hair-lines at once—part of the charm would be somehow lost from his lovely little painting. But I also believe some of the aesthetic effect of Roy Lichtenstein’s paintings would be diminished of he were to draw each and every one of those dots by hand; they wouldn’t look as much like comic book panels as he would have wanted, and we would start to be entranced by the little particularities of his brushwork when he was trying to replicate the aesthetics of the comic art as a whole. Part of the reason aesthetic questions like this ought to be answered by each artist for themselves is that every artist has a different set of concepts they are trying to get across; each artist is working with a different facet of that enormous and infinitely varied Ideal of Beauty, and so their art of necessity won’t look all the same. And there’s nothing wrong with that kind of variety.

3.

I mentioned AI image generators a moment ago. It seems likely that their greatest value would be as part of the surrealist toolkit. The surrealists introduced all kinds of randomizers into their art, from Yves Tanguy’s “Exquisite Corpse” game (still popular amongst kids) to Max Ernst’s frottage and decalcomania. Perhaps it could be argued that this emphasis on randomization is just as lazy, just bereft of valuable artistic toil, as the Pollock / Rothko / etc. kind of art; and maybe that’s true. But not all the surrealists abandoned the pursuit of artistic excellence to further their aims. The best of the surrealists, in terms of technical skill, was Salvador Dali. Dali once said:

As a small child, I learned a painting rule which I will never forget. It was in the painting class of the French Brothers. We painted aquarelles made of simple geometric elements first traced with a ruling pen. Our teacher told us: painting this well, and, in general, painting well, consists of not going beyond the line.

Not going beyond the line! Here you have a conduct rule that may lead to a whole integrity and a whole ethic of painting. There always existed two kinds of painters: those who went beyond the line, and those who, patiently, and with respectfulness, knew how to just reach their limit. The first, because of their impatience, were qualified as being impassioned and inspired. The second, because of their humble patience, were qualified as being cold and solely good craftsmen. If it is true, nevertheless, that going beyond the line is a form of impetuosity signifying always the beginning of intoxication, confusion, and weakness, it is true as well that there exists a type of passion which consists precisely of the patience of not going beyond the line; and that this passion for balance is a strong passion and an enemy of all intoxication.2

Dali himself was a superb draftsman and never colored beyond the line; there is absolutely no sloppiness at all in his aesthetic. His comment about the humble patience reminds me of this late painting of his.

What better example could there be of an artist working humbly, patiently, and with great concentration—toiling—to produce their artwork? What a lot of work must have gone into the setup, the planning, the conceptual side of a painting like this. Maybe that is where the real toil is evidenced in much of the last hundred years’ worth of art: in the behind-the scenes side of things, the conceptualizing and thinking and planning and selecting. A glorious and astoundingly superb surrealist painting such as Max Ernst’s Europe After the Rain II isn’t so much about the toil of detailed brushwork—in fact, most of what we see in Ernst’s picture is the result of squishing paint between the canvas and a piece of glass and then pulling off the glass—as it is about seeing the possibilities in seemingly random processes. It’s a species of curatorial labor, and it, just like the other kinds of artistic labor, is also a valid and worthwhile kind of work, even if it isn’t toilsome.

All of these details are from Roy Lichtenstein: A Retrospective (James Rondeau and Sheena Wagstaff, 2012). The detail view of Engagement Ring is actually a photo I took of a picture in a Lichtenstein book I found at a used bookstore in Omaha, but although the book is full of stunningly gorgeous illustrations, the text is in German. I might buy it anyway, though, just for the pictures.

Quoted in Tiny Surrealism: Salvador Dali and the Aesthetics of the Small (Roger Rothman, 2015).

The Italian painter Giovanni Bellini allegedly once asked Dürer what kind of special brush he used to get the fine hairs on a beard or animal fur. Dürer showed him a normal brush. He didn't have a special brush for that type of work. Variations of the story, whether true or not, have Dürer painting a woman's hair in Bellini's presence, to prove his skill.