The aesthetic subcultures and the floating world

With each outfit we wear and each accessory we curate, we tell a story about ourselves, our culture, and our inner world.

—Rachel Haywire1

Because they fall we love them—the cherry blossoms.

In this floating world, does anything endure?

—Ariwara no Narihira (823—880)2

I: OPPOSITIONAL AESTHETICS

Walk around the busy downtown of any major city. Walk around the buildings; walk in the park. You will see all kinds of people and nearly all of them will be wearing some variation of what counts, these days, as basic, ordinary, normal, average fashion. Their clothing choices will exist on a continuum from suits and ties all the way to jeans, t-shirts, and flip flops. There is a lot of room between these two sartorial poles; mix and match and vary the pieces and you get things like the hipster look, athleisure, business casual, the beach bum, etc.—but all of the variants you will encounter will be entirely normal and societally sanctioned forms of personal self-expression, the clothing choices of a more-or-less thoroughly assimilated and homogenous public, fully appropriate for living an average life in the modern era. Most of these people will pass into and out of your awareness without your noticing a single thing they are wearing; their very similarity and unity-in-diversity will facilitate your overlooking their fashion choices. The crowd blends into itself; their conformity to societal expectations and worldviews—their qualifying as an undifferentiated crowd—is evidenced by the way they dress.

Every once in a while, though, as you stroll through the crowded city, you will notice something different. Someone will be wearing clothes which, by their outlandishness, their bizarrerie, their eccentricity, cannot escape your notice. Perhaps someone will be wearing black clothes and cadaverous makeup; perhaps you will see someone with a wildly spiky haircut, wearing chains, patches, and safety pins; perhaps you will see someone who seems to be wearing the outfit of a Victorian-era porcelain doll. If you venture away from the real world and onto the internet, you will see an even greater proliferation of styles and outfits. The performative aspect of wearing clothes has, mostly, been relegated to social media; these strange and wondrous modes of sartorial display exist, with only a few exceptions, almost entirely online. But what does this all mean, though? Online or in real life, why are people dressing this way? You walk along the city street—you know it’s rude to stare, but you just can’t help yourself; what is going on here with these crazy kinds of clothes? What systems of thought or belief would make a person want to dress so outrageously, to attract attention to themselves in such an ostentatious way? Is there a meaning to it?

There is indeed a meaning. It is a complicated one, often very subtly expressed and possibly not what you would expect. The people who wear unusual clothes in public are manifesting distinct and deeply held attitudes toward the whole of human society and existence, and especially the problem of evil. They are all concerned with a conception of truth, beauty, or goodness which is at odds with the perceived meaning of those concepts in the broader culture; and despite their distinction and variety, nearly all of them share something in common—they all signify a deep sense of grief over a broken world.

Let’s call these “oppositional aesthetics,” and the sets of people who embrace these aesthetics, “aesthetic subcultures.” We’ve been conditioned by the culture3 to consider these people as nothing more than weird, annoyingly weird perhaps. But we really ought to study them closely and take seriously the social criticism these aesthetic subcultures represent.

The oppositional aspect of the aesthetic subcultures has its roots in the reaction to the stringent and austere economic policies enacted after the end of World War II in Britain. In response to continued shortages and rationing, some English youth began to make their own clothes and developed styles of their own: Teddy Boy, mod, rocker. They went to great lengths to cultivate their own shared sense of community and displayed that community in their clothing choices, and all of this freaked out their elders and betters, who saw these youths4 as threats to the social order. It didn’t help that some of these groups, the mods and the rockers in particular, had a tendency to harass each other and even get violent at times. But despite their shenanigans being confined, with only a few exceptions, to their own circles, the mods, Teddy Boys, and rockers met with stiff resistance from their parents’ generation. They were perceived as delinquent and deviant, an aberration, a movement to be suppressed—because the culture saw, in them, a very subtle and muted criticism of itself.

This muted criticism gained in volume over the decades following the war and was finally expressed with full force with the advent of the punks. Punk culture is complicated, multivalent, and at times confusing. There are elements of resentful xenophobia in it, sometimes, even, of fascism, but it is primarily an aesthetic movement dedicated to a reactionary nihilism: the punks saw something seriously wrong with the way the adults were taking care of things, and they wanted to tear down the whole mentality of their parents’ generation and expose its crassness and vulgarity, its emptyheaded indifference to the serious problems of the world. The combination of focused attention to details of style and dress coupled with resistance, hostility, and even hatred from the broader culture only served to entrench the punks in their own ways and give them a sturdy sense of self-confidence. It was a heady brew they were distilled from, and their aesthetic of deliberate, conscious, and loudly critical opposition to the established cultural narrative was a profound shock to polite middle-class British and American society when it emerged in the mid-1970s.

Punk culture has been analyzed to death—quite literally. What was once a source of consternation for the bourgeoisie is now just another kind of fashion choice. Punk outfits are no longer deployed as a challenge to the general culture; now they are often worn to annoy one’s own grandmother. The backbone has been ripped out of the movement’s inherent hostility to establishment values—and in a sharp ironic turn, you can go to the mall and buy punk clothes and gear at Hot Topic, which is owned by the same private equity firm5 that owns such brands as Ann Taylor, Lane Bryant, and Staples. Punk is now a performative aesthetic with about a bazillion offshoots and substyles (Aesthetics Wiki lists 48 different kinds of punk); the people who wear punk are not the angry critics of culture that they were fifty years ago. Often the label “punk” is applied to a purely visual aesthetic—cyberpunk, steampunk. What happened to the oppositional aesthetic tradition? It has gone through some serious changes—a cycle, in fact. Refer back to the diagram above and take a good close look at it, and travel clockwise around its perimeter.

The rage of the punks went unacknowledged by the culture and was subsumed into grief. What the punks saw was a broken world that refused to dialogue about its own brokenness; in turn, the punks became consumed by despair . . . and turned into goths.

Goths have been analyzed also, but not as much as the punks have; as a consequence they still have an aura of scariness about them. The culture still feels that goths are a strange and fearful thing and doesn’t know how to think about them. The culture sees goths as obsessed and fascinated with death, yet the reality is that goths are just as disgusted with death as the rest of us, but death is all they can see in the world around them. Someone once made a witticism to the effect that French postwar intellectuals can eat the best food in the world and give themselves up to the most exquisite carnal pleasures, yet still say that life is very obviously an obscene pointless horror.6 The difference between this view and that of the goths is that the average goth simply can’t indulge in the food and the carnal pleasures. For them, the sense that the world is going down the drain is so overwhelming that it overshadows everything else; it dominates their thought process, and they must admit the truth of the “obscene pointless horror” in everything they do, especially in their public-facing fashion choices and in their music.

But despair can only be endured for so long. If you indulge in despair, you end up either killing yourself—or getting over it. Just like most hardcore vegans eventually renege on their principles and become some sort of vegetarians, most goth kids end up being dissatisfied with the aesthetic’s extreme stance and start looking around for a different way to register their social protest. Many of them go goth lite: they keep the frilly shirts but they buy white ones instead of black; they throw away their fishnet stockings and wear tweed skirts instead; they take down their poster of Robert Smith and put one up of Byron—in short, they go all dark academia. No more Siouxsie and the Banshees or Love Spirals Downwards; now Schumann is suddenly cool. Donnie Darko? Nah, let’s watch Dead Poets Society or Kill Your Darlings instead.

Like goth, dark academia has a very gloomy and somber tone. Otherwise, though, the two aesthetics differ markedly in their overall concerns. Dark academia is not an aesthetic of outward-facing social protest motivated and fueled by despair. Dark academia actually represents a denial of the angsty doomism favored by goth; instead of weeping over a meaningless world, dark academia seeks to return, in the mind at least, to a world that didn’t seem to have lost its meaning yet. The aesthetic is all about seeking to overcome the tragedy of modern life by renewing a sense of meaning grounded in the strength of old traditions and ancient knowledge. Think of the students gathered around Julian Morrow in Donna Tartt’s The Secret History, studying moldy old Greek texts with no thought of the world around them. Dark academia is often charged with being elitist, which, of course, it is—who else but the elites have the option of ignoring the problems of the world? Dark academia considers the difficulties of the world to be beneath notice, something only the plebes would care about anyway; and with those clothes on you know they won’t be working with their hands or otherwise needing to earn their living. They will stay in their hallowed halls of learning, and they will study, pushing themselves ever forward and onward, ever more rigorously, toward a fuller engagement with the life of the mind.

The dark academia aesthetic signifies and communicates a sense that the petty struggles and travails that the culture gets flustered about are of no significance compared to the eternal verities of the Western Tradition. Marcus Aurelius already figured out all that existential stuff anyway, right? And the obstacles to fulfillment aren’t found out there, in a dark and dying world of “obscene and pointless horror;” they are all inside our mind and can be overcome by sustained and heroic efforts of study. More books and texts! More late nights fueled by coffee and amphetamines!

Is it any wonder, then, that the culture at large—the mob, the massed rabble, the kind of people who were always suspicious of book-learning and who would much rather venerate almighty mammon than worship at the altar of the muses—often misses the point of dark academia and sees it only as a preppy kind of elite fashion? Thinkpieces abound (here, here, and here are some good recent ones), evidence that at least the pundits are aware of dark academia and are puzzling over what to make of it. The resemblance of dark academia to a ruling elite is uncanny, though: it is true that the last time anyone in the West had a ruling class, that class wore Oxford shoes, waistcoats, and tweed jackets. Besides, those clothes . . . look good! All of the aesthetic subcultures have their own canons of taste and style, but dark academia most closely approaches the general culture’s idea of “dressing up.”

However, the people involved in dark academia can themselves forget the point of the aesthetic; they can get so wrapped up in the pursuit of it that they forget their aesthetic is meant as a reproach to the culture’s habits of easy subjectivity; they can begin to see reading, study, the hallowed halls, and all the rest as a particular set of accoutrements to the good life. This is reflected in the style known as light academia, which is not merely dark academia in summer clothes; it represents a fundamental value shift, from self-denial and striving to enjoyment and pleasure. Of course it’s “fun,” in a twisted sort of masochistic sense, to waste one’s self away in pursuit of the higher learning. But if we were honest about our own laziness, we will admit it’s more fun to read Mansfield Park than The Critique of Pure Reason or even Doktor Faustus, and it’s even more fun to do it while sitting on the balcony and sipping Earl Grey. Or to play chess while wearing a cravat. Would you rather search through musty quartos bound in calf . . . or would you rather do anything while twirling a parasol?

Light academia is serious and fun at the same time, emphasizing the more intrinsically enjoyable, pleasant aspects of the studious life as opposed to the realities of what that life is really like (if dark academia is a romanticization of the academic grind or the weight of tradition, light academia is more of a romanticization of the pose of being an elite college student). What else could be considered in this manner? At this point, light academia casts its gaze about and realizes that the real problem with modern society is that we’ve abandoned a whole slew of lifeways that are still capable of beauty, charm, and pleasure. And thus we are borne to the next spoke on the wheel; from the lace collars and tea-on-the-terrace of light academia it is only a logical step to the bonnets and picnics of cottagecore.

Let me emphasize, again, that all of these aesthetic subcultures are, at their root, cultivated reactions to the realities of modern life. As such they all present several interesting parallels with each other. Cottagecore, like dark academia, is very interested in a small subset of human activity, and it is sad for a lost way. Like the goths, cottagecore sees modern culture as irredeemably lost, and like punk, it is angry about that. But like light academia, it would much rather have fun and enjoy things than worry about their meaning. Here it would be instructive to pause our survey for a moment and mention a few other aesthetic subcultures which get their inspiration from the ones we’ve seen so far.

Most of these derivative subcultures are only concerned with promoting a visual aesthetic and do not have a specific philosophy of their own. Lolita is a derivative of punk, not goth, because it is meant to shock. Anything which builds a lifestyle around a hobby is in some sense a reflection of or antecedent to dark academia, or at least shares the same view of the world: scene, grunge, K-pop fandom, biker, surfer . . . they all take some aspect of the human dramedy and amplify that aspect until it becomes a life-defining fixation. Preppy aesthetics are either a watered-down and modernized version of light academia, or light academia is an exaggerated and amplified version of preppy. Cottagecore is the near twin of all those “cozy” mood boards on Pinterest, as well as the whole “trad wife” movement; in fact, get rid of the religious element and the need for relations with the male gender, and trad wife easily starts looking like cottagecore.

Cottagecore is the oldest of all these aesthetic subcultures—Marie Antoinette started it back in 1779 when she took charge of the Petit Trianon and turned it into her private, nearly male-free paradise. Her iteration of the Petit Trianon was a complete falsehood, though, and therein lies the difficulty: like Marie Antoinette eventually did, today’s practitioners of cottagecore find a fundamental disconnect between the outward appearance of their chosen aesthetic and the truth of the real world. Cottagecore is very easily performed on social media, but do you really think that, after the photo shoot is done, the people in the pictures actually live like that? Cosplaying the nineteenth-century farmwife ignores the realities of muscles sore from churning butter, eyes and backs ruined from bending over all the sewing, and the filthy, reeking barnyard full of animal smells. But maybe . . . those grungy, coarse, earthy aspects of life should be embraced? Civilization is, fundamentally, a grand march toward cleanliness, but maybe we should just give up on the whole business?

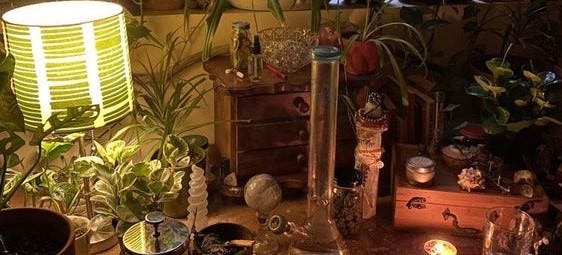

That’s where goblincore comes in. It is a movement which embraces every kind of natural, instinctual, basic impulse and rejects the entire project of civility and decorum. This is not to say that goblincore is uncouth or raunchy. Goblincore simply does not acknowledge the dirtiness of dirt, the grossness of bugs and fungus; goblincore embraces the dirt, finds it interesting. It cares about the things that culture overlooks; it is a movement of collectors of pebbles and bits of bark and moss. And if cottagecore rejects any male sensibilities and becomes almost a parody of “girly stuff,” goblincore goes even further and rejects all gender whatsoever. Perhaps you have seen this goblincore rallying cry—

—which perfectly captures the aesthetic.7 “Male” and “Female” imply relationships, propriety, decorum, civilization; goblincore rejects all that. It is feral. If Thoreau had just had the courage to stop writing, and collect cool bits of forest litter instead, he would have been the patron saint of goblincore.

Goblincore still exists in a relationship with the culture, however tenuous that relationship may be. What goblincore most desperately desires is to be left alone, but that won’t happen; the totalizing worldview of modern culture insists that all people everywhere must exist as part of mainstream society. Modern culture shudders at the goths, criticizes the dark academics, and puzzles over cottagecore; but in no case can it just let them be. In the case of the punks, culture actively tried to suppress them. Goblincore sees all this and realizes that culture is in opposition to them too; culture cannot allow goblincore to exist unmolested, because goblincore, like all the rest, is an affront to modern-day mainstream ethics and values. What was it that Pascal said about how atheists view religion? “Men despise religion. They hate it and are afraid it may be true.”8 This is how culture feels about all these aesthetics; and if ever culture directs its ire against goblincore, of all these aesthetics the one most distant from the culture’s beliefs, values, creeds, and worldview—if ever it works up a genuine moral panic, as it did with the Teddy Boys in postwar England—the beast will let out its claws. Goblincore’s reaction to the hate will be that of a caged animal desperately trying to survive. The dog, called a wolf enough times, bites its tormentors, and goblincore, finally in touch with its fiercer side, will turn into punk. At times it almost seems as though goblincore realizes that if culture would only just get torn down and get out of the way, goblincore could finally become its true, wild, feral, untamed self.

There’s a passage in Exploring Egregores, on the subject of the Lovecraftian cult of Shub-Niggurath, which is worth quoting in full in this context.

The predator within has been offered red meat, and it’s not content to stay on its leash anymore — the Man wants ease and entertainment, but the Wolf wants to be at the top of the food chain. Right now you live in a world dominated by human technology, where even a wolf with human cunning is overmatched by all sorts of things, and so your feral side has no better option than to go play when you let it and to stay quiet the rest of the time. But in the new world of the Shub Niggurath’s dream, the Wolf could rule. You would be deadlier than any man, and almost any beast. You would run across the blood-spattered snowfields, and howl at the uncaring stars, and gorge yourself on the warm flesh of your prey, as much as you wanted. It’s a possibility that you’d never really bothered to consider, for obvious reasons, but now that it’s lodged in your mind . . . you find yourself dwelling on it fondly when you’re not careful, and slipping more and more into wolf-thoughts.

True cultists of Shub Niggurath want her help to overthrow all the hypocritical artifice. Not just because it will be a “return to nature” and “heal the scars of pollution” (although that’s nice), but because only in a fully liberated world can they be themselves.9

That is the journey from goblincore to punk. The whole cycle, expressed in images, looks like this.10

II: FLOATING WORLD

Of course, the reasons why any particular person might have for getting involved in these aesthetics has the potential to be wildly different from what I’ve discussed here. And perhaps I’m wrong about the whole thing; all I can really report to you is what I see and observe in the world, and all I can really offer is some hunches about how all of these aesthetics are related to each other, if at all.11 Earlier I hinted at the correlations between these six aesthetic subcultures. A huge part of aesthetic theory is made of the cataloging of correspondences, resonances, and affinities. Recall the wheel diagram from before, but think of it like this:

As can be seen, the aesthetics can be grouped in pairs reflecting their prevailing mood towards their own personal sense of well-being and fulfilment. The wheel can also be divided down the middle with the aesthetics on the top taking a reactionary stance toward the culture—a more directly oppositional stance, perhaps—and the ones on the bottom existing as more aspirational ideologies, communities of people who think they have found a better way to live than what the culture presents. Another way to think of all these aesthetics is to give them slogans like this:

“The world is rotten, and—

—we cannot bear that it is so” (punk, goth)

—we aren’t going to let that truth bother us too much” (the two academias)

—we found a better alternative” (cottagecore, goblincore)

Or, perhaps, think of the transitions between the six aesthetics as a series of cognitive movements, like this:

Punk to goth: falling into despair

Goth to dark academia: resignation to circumstances

Dark academia to light academia: corrective nuancing

Light academia to cottagecore: broadening of scope

Cottagecore to goblincore: carrying to logical limits

Goblincore to punk: turning from private to public protest

Maybe we can gain some insight by tabulating the aesthetics by color, emotion, preferred physical environment, and defining fashion accessory?

PUNK: red—rage—subway—mohawk hairdo

GOTH: black—grief—mall—black nail polish

DARK ACADEMIA: brown—neurosis—academy—waistcoat

LIGHT ACADEMIA: white—fascination—house—frilly shirt

COTTAGECORE: yellow—love—farm—blanket

GOBLINCORE: brown—longing—forest—satchel

Notice, also, that in social media posts or Pinterest boards, people performing the three aesthetics on the “reactionary” side will, most often, be shown facing the viewer, but images of people from the three “aspirational” aesthetics will be seen with their backs to the viewer, from neck down, or otherwise with their face obscured; sometimes, even, what’s shown isn’t people so much as objects, accoutrements, lifestyle props. This is because the three aspirational aesthetics are involved in the question of glamour, which requires illusion and distance—they present themselves as a way of life to be desired, a better and higher way, and the point isn’t the people, it’s the vibe.12

You could also draw a line from the upper left to the lower right of the wheel; the aesthetics would then be arranged along the axis from a “dirty” pole (goblincore and punk) to a “clean” pole (the academias) with cottagecore and goth existing at the neutral node. One more, one more: take any aesthetic and match it with its opposite on the other side of the wheel and you will get a kind of yin-yang dualism: goth / cottagecore are gloomy / sunny, punk and light academia are hard / soft, and goblincore / dark academia are wild / civilized. The big point to remember, though, is that all of these aesthetics are different ways of trying to make sense of the problem of evil and the brokenness of the world. “The world is broken and that’s not acceptable” is what they all are saying, to a greater or lesser extent. In that regard they are all rather similar to what the philosopher Albert Murray called “The blues idiom.” In an article on Murray, the blues idiom, and American religious life, Alan Jacobs states it like this:

The blues idiom begins with the recognition that—Murray uses many variations on this phrase—“life itself is such a low-down dirty shame.” But it doesn’t end there. What matters is how one responds.13

How one responds . . . there is, of course, always the option of not responding at all. I want to direct your attention to the bottom of the wheel; there at the bottom is light academia, and if by now you get the feeling that of all these aesthetic subcultures, this one seems most in it for the mere appearances, is the most indifferent to the problem of brokenness, you are correct; it also happens to lie closest to what is below the wheel, in the land of the floating world.

The floating world is dandyism; it is a preoccupation with beauty for its own sake, and it is always pulling at the six oppositional aesthetics like a giant planet acting as a gravity well. It beckons and entices, offering the option of forgetting this whole gloomy blues idiom / broken world moodiness and instead caring for outward appearances only. We’ve already seen how a great deal of punk iconography and signifiers have been co-opted into a merely performative, visuals-only aesthetic. The same is possible for all of these aesthetics; all of them can be done without recourse to the philosophy which undergirds them. The floating world has its own philosophy—aesthetics for aesthetics’ sake; a hedonistic enjoyment of the pleasures of life without thought to their significance or meaning, and certainly without thought for the broader existential questions which are the basis for the oppositional aesthetics. If the underlying assumption behind the oppositional aesthetics is “the world is broken and that’s not good,” then the underlying assumption of the floating world is “the question of the world’s rottenness is not an interesting one; it may very well be rotten but we don’t see why we should care.” Recall the French Philosopher parody from earlier, and invert it: the floating world, when told that life is very obviously an obscene pointless horror, shrugs its shoulders, raises its eyebrow, and turns to the pleasures of the table and the drawing room without a single prick of conscience, with supremely untroubled and indifferent abandon.

This “floating world” view of things has a long history. It popped up in the royal courts of Europe with regularity. In 19th-century England it was adopted as a pose by some members of the upper class, most famously by George “Beau” Brummel, who invented modern men’s evening wear, and by Oscar Wilde, who, in the introduction to A Portrait of Dorian Grey, penned this famous / notorious credo: “All art is quite useless.” The aesthetic had its fullest flowering in Tokugawa-era Japan, where it recieved its name: the era of peace and social stability which began in the early 1600s left the samurai class with nothing to do, so they devoted themselves to lives of aesthetic enjoyment in the specially crafted pleasure district of Yoshiwara. There, they cultivated an intense and refined appreciation for “the beauty of impermanence, the thrill of transience, and the meaningless existence of the individual.”14 The life they lived was celebrated throughout Japan in exquisite woodblock prints which detailed every aspect of the “pointless pursuit of pleasure” independent of the petty, mundane, everyday concerns. “Living only for the moment, turning our full attention to the pleasures of the moon, sun, the cherry blossoms and the maple leaves, singing songs, drinking wine, and diverting ourselves just in floating, floating, caring not a whit for the pauperism staring us in the face, refusing to be disheartened, like a gourd floating along with the river current: this is what we call the floating world,” wrote Asai Ryoi in 1661.15 Life is very obviously an obscene pointless horror? Um, as if!

This aesthetic—this Whistler-in-the-Peacock-Room, nothing-really-matters, Lord Henry Wooton / Robert de Montesquiou aesthetic, this aesthetic of decadent uselessness, is the exact opposite of an aesthetic defined by a search for something more borne of a dissatisfaction with the brokenness of the world. And it is beautiful. I can think of little that is as aesthetically perfect as some of the terrifyingly voluptuous paintings of Gustav Klimt, or the line drawings of Aubrey Beardsley, or the ukiyo-e prints of masters such as Hokusai or Hiroshige—their conception of line, form, and color is unparalleled. These artists worked at their craft with a singularly focused, all-consuming passion, yet were satisfied to use that passion in service to nothing greater than their art itself.

“Art for art’s sake”—what a deliciously enticing, gloriously attractive concept! To be concerned with art and with beautiful things, and to not have to justify them at all or relate them to anything else going on in the world! To be an artist—a creator of culture, of civilization—without having any responsibilities!! Do you understand, by now, how tempting this philosophy can be?

What a contrast between the earnest and at times incomprehensible striving of the oppositional aesthetics, and the carefree decadence of the floating world! The question of how to balance these two opposites—how to hold in tension the belief, on one hand, that one’s entire life (and especially one’s visual environment and manner of dress) should reflect the reality of what you see in the world at large, and on the other, that whatever is happening in the world is of no concern to one’s private conception of what is good or true or beautiful (emphasis on beautiful, of course)—is one which will continue to preoccupy many people for a long time to come, as our society continues to grapple with the fallout from the turn-of-the-millennium blues that was the death of modernism and the de- and re-enchantment of the world. What is your choice? Or at least, are you now less likely to look askance at the kids these days and the crazy clothes they wear?

Much gratitude to all the people who discussed these ideas with me on Substack notes, as well as my squad of early readers who reviewed various portions of this essay in draft form; you are all much appreciated, thanks immensely!

From “Cyberpunk Fashion: The Chronicles.” Cultural Futurist, March 27, 2023.

Quoted in Ching Yee Lin, “The Pursuit of Pleasure: How the Floating World Defined Edo Japan,” The Collector, March 18, 2022.

Unless stated explicitly otherwise, in this essay “the culture” refers to the general, mainstream, bourgeoise, human-herd culture-at-large to which the various aesthetic subcultures exist in opposition.

Sycamore Partners, in case you really wanted to know.

Pascal, Pensées, number 187.

From “Shub Niggurath, the Black Goat of the Woods with a Thousand Young.” Exploring Egregores, August 7, 2017. Exploring Egregores is the best and most absolutely crazy high-concept old-school blog you will ever discover.

Nearly all of these pictures were taken from Pinterest mood boards (the image alt text is a link to the relevant image source) and represent a real person either practicing the aesthetic or choosing the image as an expression of their aesthetic.

And if there is anyone reading this who is a practitioner of any of these aesthetics—I would love to talk with you about it, about your personal motivations, and if you think I’m way off the mark in any way; you can send me an email via this link.

I am indebted to a. natasha joukovsky for sharing this insight with me; and she would know a thing or two about glamour.

Alan Jacobs, “The Blues Idiom at Church.” Comment, Spring 2023.

This quote (and the next) from Ching Yee Lin, “The Pursuit of Pleasure: How the Floating World Defined Edo Japan.”

Quoted in Philip McCouat, “The Floating Pleasure Worlds of Paris and Edo,” Journal of Art in Society.

Thank you for this. Even as an afashionable person myself, I track all these worn forms of modern discontent. And the floating world is truly the ultimate utopia.

This is an absolutely fascinating read, spot on in so many ways. Well done!