William Morris, the greatest painter who ever lived

It can be hard to describe William Morris to people who have never heard of him. “He was an interior designer.” “He was a socialist.” “He was involved in the Arts and Crafts movement in England.” “He was a polymath.” That last one is probably the best way to describe him; he had his fingers in all the pies in late-nineteenth-century English artistic society—sometimes it seems he was everywhere, doing everything with a boundless energy. He wrote enormous amounts of poetry on medieval themes; he was a key player in such disparate fields as the development of modern fantasy literature, the revival of traditional handicrafts, and the Utopian Socialist movement. He designed stained-glass windows; he made tiles, wall hangings, furniture . . . you get the idea. He was everywhere. About the only thing he didn’t do was shave. I’m reading Fiona MacCarthy’s massive biography of him at the moment;1 he seems quite an interesting character, and it seems evident that the key to understanding Morris’ psyche is that he cared about things. That statement can be taken two ways: Morris cared about things—physical objects and places—but he also cared about things in a way that is not often encountered, especially in our hectic, distracted, post-industrial-revolution society. Morris was concerned about the everyday world and the furnishings that surround our lives, and he thought that these kinds of things were vital to the well-being of the whole person. His credo was “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.” Even little details like wallpaper were, for him, not inconsequential; nothing was not worth doing well. He was also the greatest painter who ever lived. But we’ll get to that in due time.

Could it be that the fragmentation often noted in our modern mode of living makes it too emotionally expensive for us to care about our jobs? I’ve worked in blue-collar trades for most of my adult life, and this is something I’ve seen over and over: the production worker employed by some corporation and paid by the hour to produce according to plan finds very little reason to care about what they are doing. Why, indeed, would they care? What difference would it make? They are supposed to be following someone else’s plan and sticking to the blueprint given to them by the design team up in the office. They aren’t allowed to express any individuality in the work they are doing; besides, they’re going to go home at the end of their shift and culture tells us to keep work separate from our personal lives. Work is what you have to do to get the money to afford the things you want to do. You care about your “real life,” whatever that might be, but not about your work—despite that work being, in all likelihood, the most substantial way you contribute in a productive fashion to the broader society as a whole. Shouldn’t you care about that work? Maybe . . . it should be what you care about the most? Does it make sense to give the bare minimum at work and care enormously about whatever esoteric hobby or arcane interest you might have?

These thoughts of mine are, obviously, rather haphazard and not fully formed.2 The above paragraph is an exaggeration, of course, but it sketches the outline of a distressing tendency I’ve noticed in modern culture: a culture of indifference, of I-just-work-here-ism, which threatens the bedrock of society. But William Morris stands as an example of what it could mean to live a life of intense caring.

Morris was an interior decorator by profession; each decorative art was, for him, so important that he would personally learn how to practice them himself, so he could understand them. In today’s world, what would it mean for production workers (and that category would certainly include jobs like software developers and “knowledge workers” as well as people cranking out widgets in factories) to exhibit a similar level of care for the tiniest details of their jobs? Is it even possible for our contemporary society to allow that sort of caring? If we indeed started to care about our contribution to society in such a deliberate and intense way, would we grow to see some aspects of modern life as actually harmful to human flourishing? This is a subject I’m not even going to touch because there are thinkers who have discussed it much more eloquently than I can; besides, I was planning on writing about William Morris—the greatest painter who ever lived—and it seems I’m getting off track a little.

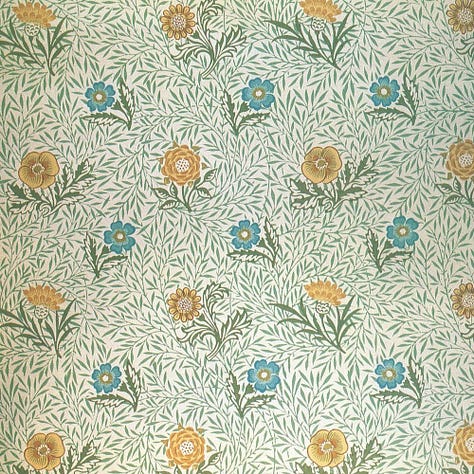

Above are some examples of wallpapers that William Morris designed.3 Before I started reading extensively about the Pre-Raphaelites (of which Morris was an adjacent figure), probably all I knew about Morris was that he was involved, in some way, with domestic furnishings. His firm, Morris and Co., designed all kinds of domestic appointments of which Morris’ printed fabrics and wallpapers are probably the most enduringly well-known. His designs are indeed beautiful and excel in quality, yet I have absolutely no context for an appreciation of them. This puts me in a strange place as a critic. Were his designs representative of the period? Did they stand out from other wallpaper made at the same time? What did the Victorians think about Morris wallpaper—was Morris merely supplying something which had a large market already, or was he being truly innovative? What did people think of wallpaper in general? The simple fact that Morris and Co. remained in business and kept producing different kinds of wallpaper leads me to believe that there was indeed a demand for their products, and that the view shared by Timothy Hilton in his book The Pre-Raphaelites was probably not a common one:

There is never in Morris’s art, whether in his poetry or his handiwork, any sense of energy, of movement or progression. This is surely the reason why Morris’s art is so repetitive and so boring. For boring it is. The classic elements of tedium are all present. First of all, it is largely anonymous: while the style is recognizable, there is no feeling of a single distinct artistic personality. Secondly, it is repetitious. There are variations of style, certainly, but they are small, and not at all like the variations of style in painting. The ability to reproduce is the enemy of any impulse to progress. And there is no progression, for Morris’s objects always assume the inertia of the endlessly echoic, willingly abandoning the ability of art to surprise. Thus the classic method of Morris’s art is patterning, and his classic production is wallpaper, wallpaper. As is often glibly said, the human eye delights in pattern; but pattern is not an adequate substitute for composition. Furthermore, pattern is only pleasing when kept within bounds. The bounds need to be those of a picture-frame, not those of a whole room. Just as rooms need windows, they need pictures; but no picture could properly exist in a room draped in Morris paper. The whole concept of wallpaper is an insult to the human eye’s ability to distinguish one thing from another. So too is Morris’s poetry, so very like wallpaper in that there is no reason for it ever to stop, and so too is the third aspect of Morris’s boringness, the fact that his productions, though not entirely (for nothing is) meaningless and unemotional, all tend in that direction. 4

I myself am not a connoisseur of wallpaper; I’m rather indifferent to it. I’ve never lived in a house that had any. Absent any kind of context for appreciating Morris’ wallpaper designs I find that they speak to me directly and without mediation in a way that is rare for art to do: most art comes to me with a historical context that informs and influences my understanding of it. But Morris’ wallpaper designs are able, for me, to exist on their own, as isolated artistic artifacts. They stand or fall on their own merits alone, without my needing to know anything at all about the artist who made them. This ought to be a characteristic of all craftwork and art made for the domestic sphere; it should be able to become anonymous and to blend seamlessly into the lives of the people who live with it. In these days, where we are coming out of a multi-century fixation on the person and personalities of artists and where even architecture—thought by Morris to be the starting point of all successful art—is replete with “stars” and big, important names, it is wise to consider what an art would be like if all the ego, the fame, the striving, was simply gone, and if artists were to give their time to making, in line with Morris’s thoughts on the matter, “beautiful useful things.”

William Morris painted the above picture in 1859. It is meant to be a portrait of Iseult from the Arthurian legends; Iseult, betrothed to king Mark of Cornwall, instead drinks a love potion and falls for Tristram, the knight who is supposed to be escorting her to her future husband (who also happens to be Tristram’s uncle). The model for Iseult was Jane Burden, whom Morris would later marry. Burden’s physical appearance captivated the Pre-Raphaelite painters, most notably Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who would paint her, in increasingly misty and voluptuous guises, for the rest of his career.

This painting of Iseult by Morris is the only extant painting from his hand.5 Yet Morris’s painting is a well-known Pre-Raphaelite classic: La Belle Iseult is reproduced in every book about Morris and the Pre-Raphaelites that I’ve seen. Think about that: one hundred percent of the paintings produced by Morris have entered the public consciousness as masterpieces of their kind and style. Compare this percentage with other famous painters. Picasso? He made an enormous amount of pictures including some very famous ones; but he made many, many paintings, especially during his last decade, that no one ever looks at. Van Gogh is the same way. He created finished canvases at the rate of over a dozen a month in the last three years of his life, but I doubt that more than a small fraction of those are known by the average art-lover; there’s just too many of them. What about someone who wasn’t so prolific, someone like Vermeer? he only made 34 canvases that we know of; but even my Vermeer book at home shows me only about twenty of them. Leonardo fares a little better. Most of his paintings would probably be included in lists of the great works of the Italian renaissance; however, a quick search on Wikipedia showed me several Leonardo paintings that I had never seen before.

But Morris? —He outshines them all. If we consider painterly greatness as the percentage of pictures which have entered The Canon, Morris is the cream of the crop. One hundred percent!

You can’t get any better than that!

William Morris: A Life for Our Time (Knopf, 1995)

Eventually I hope to write at greater length about Morris, the Arts and Crafts movement, and related topics.

They are all reproduced from Elanor Van Zandt, The Life and Works of William Morris (Shooting Star Press, 1995).

Timothy Hilton, The Pre-Raphaelites (Thames and Hudson, 1970), p. 171-172.

Well, technically, there is one other. He helped in the painting of the frescoes of Arthurian scenes in the Oxford Union debating hall; but as Timothy Hilton tells it, “Not one of these young men knew anything about fresco technique. The walls, newly built, had damp plaster on them. No ground was used apart from a coat of whitewash. Some of the paint sank in, some of it flaked off. The hall was lit by gas lamps, whose fumes badly damaged what was there. The Morte d’ Arthur faded away: Launcelot’s Vision of the Sangreal, Sir Pelles and the Lady Ettarde, King Arthur and Excalibur, Sir Gawaine and the three damsels, all perished, Morris’s work being the first to disappear. After six months all that was visible of his painting was a portion of Sir Tristram’s head, and a little row of sunflowers.” —Hilton, The Pre-Raphaelites, p. 164.

People are slagging off William Morris? Then they misunderstand. His greatness was that he took something that IS everyday, boring, repetitive and elevated it to a thing of beauty when the public likely wasn't demanding it.

That excerpt about wallpaper being boring made me think of genAI.