iPhones, Idols, and Icons: resisting image saturation

A report from the Triangle Conference on Theology and Culture

Editor’s note: today we are very pleased to be able to bring you the writing of Carolyn Etzel Branch, who writes about the intersection of theater and theology at The Rewilding Script. Recently she visited Triangle Church in Durham, NC to attend a lecture on a topic of profound interest to the RUINS editorial staff: the role of images in our current cultural moment. Images of all kinds have been potent sources of meaning throughout human history; but these days it seems there are so many of them—especially in the digital realm—that it can be hard to notice what images are doing to us. In what ways does this constant flow of imagery affect our thinking—about ourselves, about others, about God? Without further comment, then, here is Carolyn’s field report.

On a steamy midsummer morning in North Carolina, I turn into the circular drive of Triangle Grace Church and park. The church building wins me over immediately—wildflowers exploding in their beds, round windows, arched brick doorways, the curve of a columbarium set back a ways in the trees. Someone here cares about beauty.

I have arrived for the church’s two-day Triangle Conference on Theology and Culture: iPhones, Idols, and Icons. Triangle Grace Church holds free conferences a few times a year as a means of creatively engaging with culture while practicing hospitality towards the greater Research Triangle community.

This weekend, the conference features Dr. Matthew Milliner. Dr. Milliner teaches art history at Wheaton College, is a six-time appointee to the Curatorial Advisory Board of the United States Senate, and writes the monthly “Material Mysticism” column for Comment magazine. He has written extensively about images and their place in the world; his two books are The Everlasting People: G.K. Chesterton and the First Nations and Mother of the Lamb: The Story of a Global Icon.1 The topics for the weekend center around the issue of image saturation. Life within a digital culture means we are awash in visual content, often to the point of valuing the image over text in communication. The internet affords us constant, instant access to perfect images: is this image saturation a bad thing?

Dr. Milliner recaps his first talk from the previous evening with a selection of book recommendations, most featuring some combination of the words: “anxious,” “digital,” “generation,” and “toxic.” In particular, he refers to an essay by Ross Douthat titled “An Age of Extinction is Coming. Here’s How to Survive.” Afterwards, I scroll the article, itself spattered with advertisements for an AI assistant offering to do my writing for me. The article explains that the reductionism of digital content is pressing us towards a cultural bottleneck in which “languages will disappear, churches will perish, political ideas will evanesce, art forms will vanish, the capacity to read and write and figure mathematically will wither, and the reproduction of the species will fail—except among people who are deliberate and self-conscious and a little bit fanatical about ensuring that the things they love are carried forward.”2

Bleak.

Subtler and perhaps more troubling, the digital world confronts us with a false sense of the infinite, and this is where Dr. Milliner is heading today. The image saturation of the internet lures us towards a pseudo-world of images so perfect and easy they have been stripped of any humanity, where none of the fragility or mystery of human life can unsettle us or call us towards heaven.

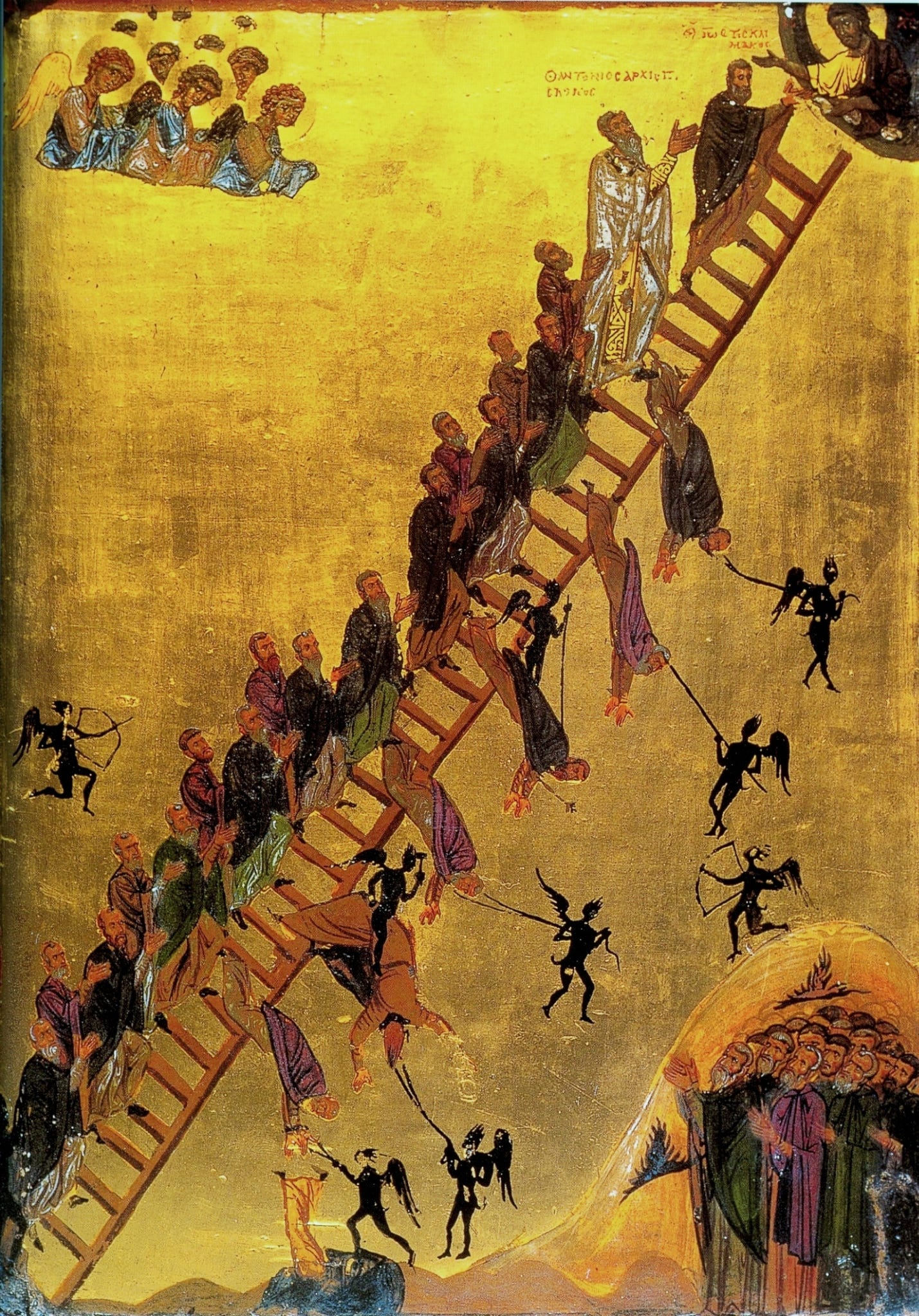

This morning we’ll be looking at the particular vices of an image-saturated culture through the lens of art history. Dr. Milliner displays the Ladder of Divine Ascent Icon for us, which portrays monks clambering towards heaven while being assailed by various demons, each of whom represent one of the Eight Deadly Thoughts. These thoughts are a precursor of the Seven Deadly Sins introduced by Cappadocian monk Evagrius Ponticus, to whom we’ll return in a moment. Dr. Milliner walks through each of the Deadlies, defining them and explaining their role in the digital world.

Gluttony—a vice which ranges from eating ravenously and excessively to consuming fastidiously. Our phones aggrandize this temptation, inundating us with opportunities to fixate over food beyond a means of pleasurable nourishment.

Lust—a perversion of sexual desire. As Milliner explains, we hardly need to expound on the ways the internet invites us to objectify ourselves and others, from social media to the pornography industry.

Greed—an intense selfish desire. The online world makes it impossibly easy to see something you like and make it yours with only a few clicks. It will even learn what you like and find more pictures of those things to show you, without you even having to seek it out.

Anger—while anger is not inherently wrong in the Christian tradition, it so very easily slips towards wrath. Dr. Milliner explains that posts, videos, and images that arouse anger or controversy—rage bait—have better engagement online. We congregate around outrage.

Envy—That which originates with a comparative notion of self, says Dr. Milliner. Social media in particular overwhelms us with images of those around us, stoking us towards envy over admiration.

Vainglory—excessive pride or vanity in one’s accomplishments. The digital world provides us with constant opportunities to craft narratives of only our successes, to risk the “humble brag” in hopes of tempting others’ envy.

Listlessness—sometimes labeled as sloth, but Dr. Milliner prefers this term, which captures the dejection, restless escapism, and busyness included in the original idea. Quick, constant digital images lure us towards doomscrolling, a mindless, restless numbing of our true selves.

Pride—he likes this definition: “a perverse desire for preeminence over others.” The internet encourages a superiority complex. It is so easy to feel as though you know everything from a momentary search, or to assert your remarkable insights to others.

There’s no need to marinate in catastrophe; no one is laboring under the misconception that a boundary-less embrace of the digital world edifies us. But each of these Deadly Thoughts are a doorway into that age-old temptation to make gods of ourselves. Here is an apple, a tower of Babel, where with very little effort and flawless visuals, perhaps even false ones generated from the stolen art of human creators, you can craft your own eternity. This pseudo-world lures us away from true humanity, away from life abundant towards an oversaturated atrophying pixilation. Come in, and confuse glory with gratification.

Image revolutions are not a new concept. Dr. Milliner points to the shift between medieval and renaissance art; Christian limited-perspective iconography giving way to immersive scenes of humanism, individualism, and secular life. Just as with the dawn of the internet and its image-based culture of immediacy, people grew nervous that the new frontiers of art would cultivate new sin.

Dr. Milliner’s use of the Eight Deadly Thoughts is not to conjure undue panic over the internet, but to point out that sin, like energy, is neither gained nor lost over time, only converted. Those vices which plagued the monks of the patristic era have only reinvented themselves; we have neither morally progressed nor deteriorated.

Throughout his presentation, Dr. Milliner narrates the story of Evagrius Ponticus, the man who coined these Eight Deadly Thoughts. Raised among the Cappadocians, Evagrius journeyed into Constantinople to rally against the Arian heresies, only to find himself tangled in some vague romantic indiscretion. From there, he fled to Jerusalem to shelter under the leadership of Macrina the Younger and her monastic orders, before she sent him into the Egyptian desert to the African monks there.

Dr. Milliner pauses to show us some photographs of extant art in the Cappadocian cave churches and the African cells where Evagrius lived. He twirls a laser pointer around some ceiling murals of the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist as they point towards Christ, noting the damage to the art caused by time.

“Isn’t it wonderful?” He says. “The only images you can trust are those that are broken, because they lead us to grace.” We follow his gaze towards Christ in the middle, his undamaged figure revealing the marks on his hands and feet.

In one such Cappadocian church, a now lost inscription once read, “The image itself is insignificant (which you have before your eyes.) But mighty is He who carries upon Himself the image of the Infinite. Worship the prototype (of which you have here only an image.)”3 In these spaces, images functioned not only as a means of beauty, but as a window into transcendence.

In dim, prayer-filled cells, nourished by the desert monastic tradition, Evagrius grew into a wise and well-respected scholar. Students and penitents flocked to the wilderness to learn from this ascetic, requesting his insight and prayer. The desert mothers and fathers were renowned scholars and healers, trusted to diagnose the demons assaulting a given individual and able to offer them antidotes in scriptures, prayer, and images. Visuals of grace were assigned to cut through the weight of sins.

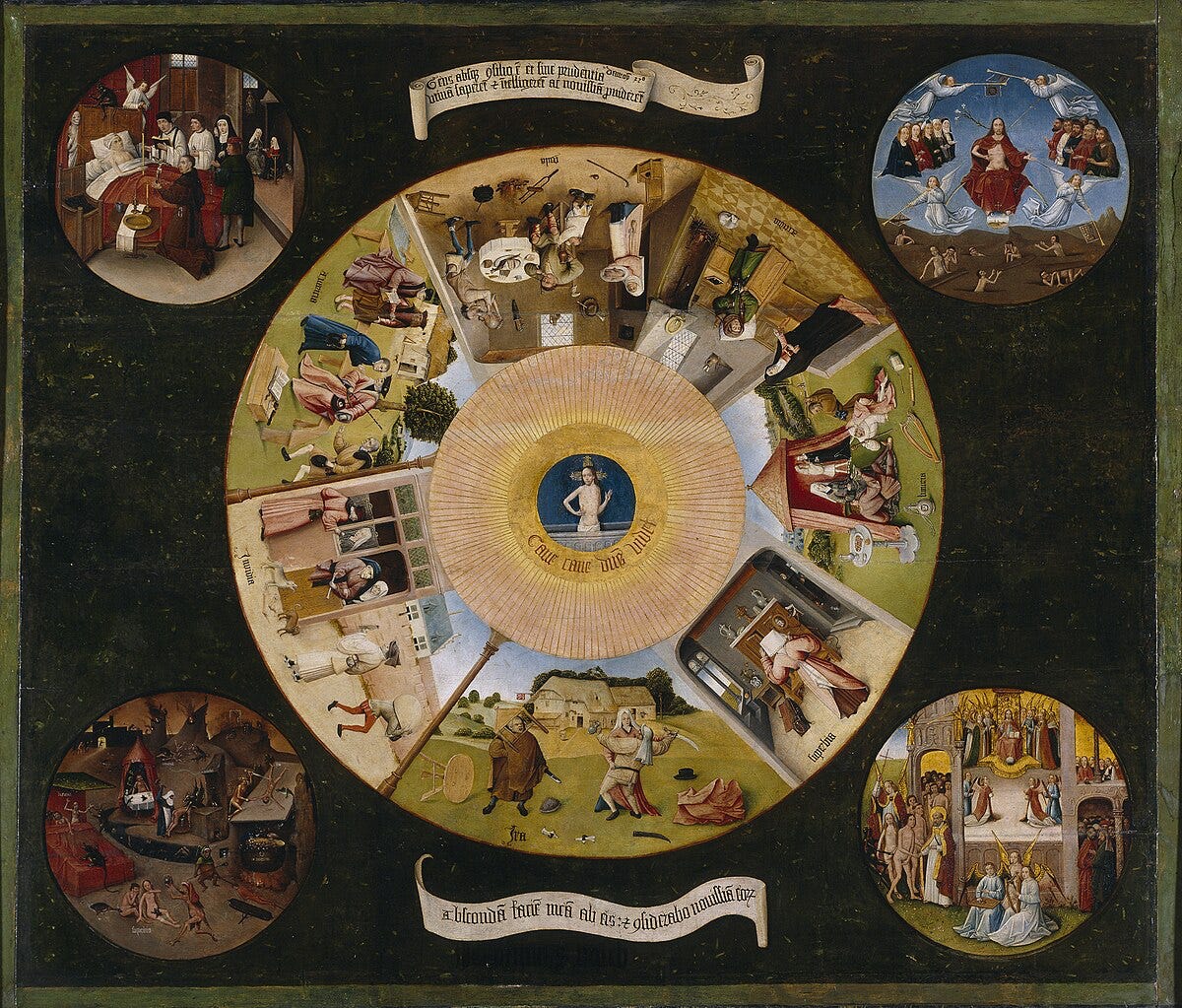

Dr. Milliner shows us such paintings, one of which portrays a deer ensnared by serpents opposite the same animal freed by grace. Images of the Seven Deadly Sins or Evagrius’ Eight Deadly Thoughts also arise from this period and continue throughout art history. In many visual representations of these vices, the images include the eyes of Jesus. One implication of his gaze is that God sees all, that final judgment will lay bare and make right every wrongdoing. But in another sense, this image follows the desert monastic tradition and reveals the antidote to these vices: to be beheld by grace.

Our sins are timeless, merely formatted anew in pixels; but their antidote is equally enduring. Although the conference has leaned into the dangers of image saturation and a digital life, it has also offered a few examples of visual art’s power for attuning us to truth, beauty, and goodness. Images themselves are neither good nor bad, but they may either lead us towards idolatry, or towards the Image of the Invisible God, our wounded icon of divine love. The digital world is not inherently evil, but it can distract us from the gaze of Christ by making our own eyes our gods.

“Images, at their best, are wounded,” says Dr. Milliner. The best visuals do not seek to erase all limitations, but to communicate perspective and message through them. I leave the conference reflecting on his message, one that is frank yet tempered by a potent hope of grace. Saturating ourselves with perfect, instant images tempts us to conjure a false sense of the infinite in our own beholding. Rather, we need to measure our engagement with the digital world by its ability to summon us to the true infinite, the eyes of Jesus, beholding us with grace.

Related reading from the RUINS archive

Ross Douthat, “An Age of Extinction Is Coming. Here’s How to Survive,” The New York Times, April 19, 2025.

Spiro Kostof, Caves of God: Cappadocia and Its Churches (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 91.

Great to hear how Dr. Milliner situated the digital onslaught within the larger history of how Christians have sought Christ within the imperfect artistic world! Well done, Carolyn.

One thing: how did the other panelists figure into his comments?

Great article, this is my favorite quote:

“Isn’t it wonderful?” He says. “The only images you can trust are those that are broken, because they lead us to grace.” We follow his gaze towards Christ in the middle, his undamaged figure revealing the marks on his hands and feet.

In the world but not of the world comes to mind.