Jesus Through Medieval Eyes (Grace Hamman, 2023)

There is a terrifying and awe-inspiring mosaic in the Cathedral of the Transfiguration at Cefalù, Sicily, one of a number throughout Europe of the genre known as Christ Pantocrator. It is an enormous picture, filling the apse of the Cathedral and towering over the worshippers assembled below. In the mosaic, Christ glares down at the rest of the church with a powerful, transcendent gaze; he appears very “other,” totally serene and at the same time intimately involved with the world here below—as the title of the painting indicates, he is shown in his role of “God who can do everything” and even “God who has done everything.” Looking at this picture, my first thought is of the holy fear that is sometimes referenced in the Bible; my second thought is that, despite the striking physical similarities, this ain’t no Warner Sallman Jesus.

My own mental image of Jesus has, I’m sure, been distorted by Sallman’s 1940 painting Head of Christ, and it’s something I try to fight against as much as possible. In her new book Jesus Through Medieval Eyes, Grace Hamman advocates for a strikingly original and clever method of counteracting our own internalized misconceptions: why not look at Jesus through the eyes of other people whose assumptions and perspectives were different from our own?

As she phrases it in the book’s first chapter,

We all have our own ideas about who Jesus is, ideas mired in our cultural expectations of saviorship. With varying degrees of self-awareness, each one of us may worship self-help Jesus, historical Jesus, super-angry Jesus, archconservative Jesus, lefty anarchist Jesus, or some combination thereof. Sometimes these caricatures capture aspects of Jesus well, but they exaggerate some features while diminishing others. Sometimes they distort him beyond recognition.

[C.S.] Lewis helps us here. The traditions and writings of the church of ages past are a gift. They keep, in Lewis’s memorable phrase, “the clean sea breeze of the centuries blowing through our minds,” clearing out the accumulated musty air behind the closed doors and windows of our own assumptions.

“Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater” is surely an applicable phrase when discussing Medieval theology. The people of the Middle Ages had their share of errors, heresies, and other faults, but they also had many valuable insights; unfortunately these insights can be easily overlooked. Speaking as a member of the Protestant tradition, I often feel a great disconnect with the history of my own religion. To hear some Protestants discuss the issue, you would think that Martin Luther invented Christianity in 1517. But if we recall that Luther lived and wrote three-quarters of the way into the history of the Christian religion, a sense of humble perspective ought to prevail. Are we really to believe that none of these people had any insights, anything of value to pass down to us?

Hamman’s book is a vital corrective to the kind of solipsism that can easily categorize the approach of some, but not all, modern thinkers. Each chapter of this book examines a different way in which we might find ourselves at odds with the medieval church’s understanding of who God is—and then asks us to seriously consider what we might learn if we see these issues “through medieval eyes.”

As an example of this approach, consider Hamman’s chapter titled “The Mother,” which discusses maternal imagery associated with Jesus. Here, she describes this metaphor and how it was perceived by the Medieval church:

The metaphor is not new, New Age, or about Christ’s biological sex as a human; it is grounded in robustly theological and biblical metaphor. In fact, themes of labor, pregnancy, and embodiment appear throughout Scripture as an unfolding way of understanding divine, authoritative, and sacrificial love.

The medieval writers and thinkers which Hamman cites took these Scripture passages very literally, and tied them to the concept of Christ’s suffering. The logic went like this: Christ’s suffering was for a purpose, just like the suffering of a woman in labor is for a purpose. Even more, Christ’s suffering can be seen as the matrix from which the church was born. Hamman reproduces two astonishing images to illustrate this point. One, from a mid-13th-century book, shows Christ on the cross, and the church, represented by a little man with a crown and chalice, actually coming out of the wound on Jesus’ side. The other image, from a Norman prayer book of the 14th century, goes even farther: it depicts Christ’s side wound as a vulva. These pictures stretch the metaphor to the extreme limits of logicality—but they are honest and sincere in their wrestling with a concept that can seem very hard to understand: the meaning of Jesus’ agony on the cross.

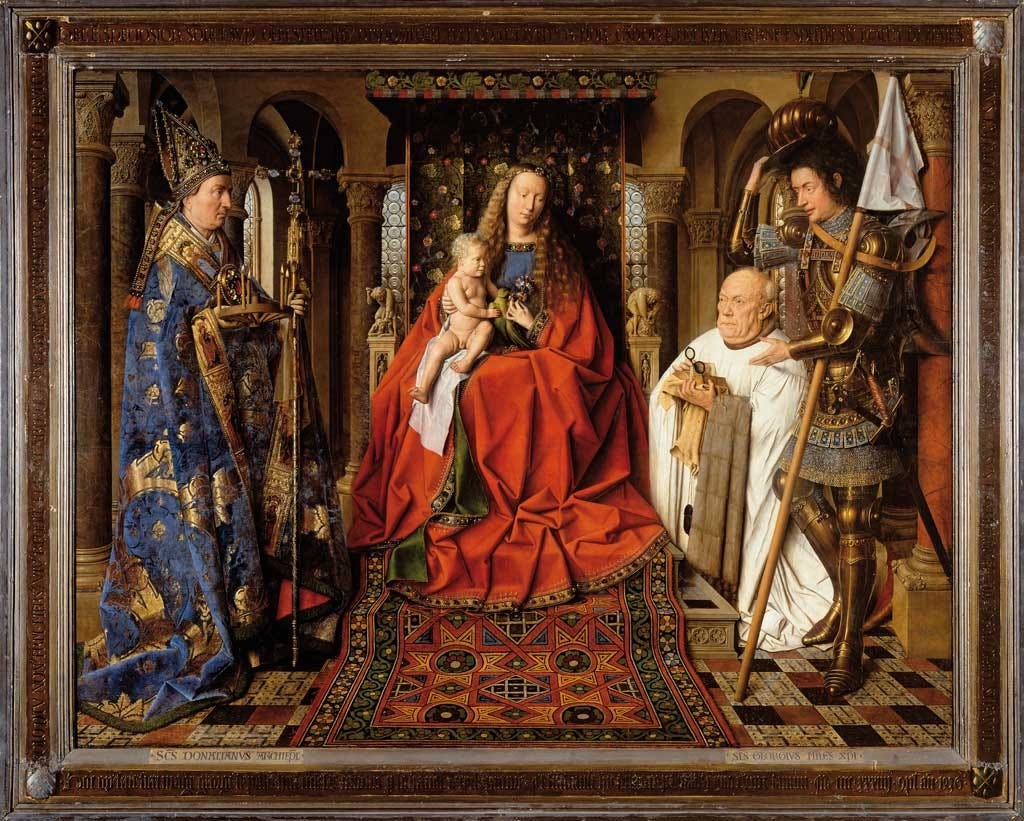

Perhaps Medieval Christians were more willing than us to think in images. They did not confine their speculations to the usual channels of theological discourse but spilled them out in a profusion of pictures and decorations on their prayer books. In a chapter called “The Good Medieval Christian,” Hamman examines the genre of paintings which include the owner or commissioner of the painting as being actually present at the events described in Scripture. She shares a picture from a prayer book showing the owner of the book assisting the Archangel Gabriel at the Annunciation. I’m also reminded of the painting by Jan van Eyck called Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele, one of the most moving images of personal piety I’ve ever seen. “Too presumptuous,” we moderns might say; “there’s more than a little hubris in putting yourself right there in the action.” Well . . . “You are too detached from the story,” a voice from the Middle Ages responds. “You ought to take seriously the scriptural passages which speak of us partaking in Christ’s ministry.” It is a very natural and human thing to say “I wish I had been there;” perhaps we of the twenty-first century ought to let ourselves express those imaginings more concretely, more imagistically—more medievally.

There were a few times, though, when I found the Medieval perspective simply too strange to consider objectively. Hamman’s chapter “The Lover” explicates a line of thought which is very difficult for me to endorse. Perhaps I, too, have been misled by the excesses of purity culture, and perhaps I’ve swung too far in the other direction, thinking of Jesus’ love as only a platonic, cerebral kind of love. For the medieval writers and illustrators whom Hamman cites, Jesus’ love was certainly not limited to matters of the mind; and some of what these writers describe seems extremely hard to accept. Hamman reproduces a woodcut from a German prayer book which depicts Jesus “tenderly undressing a soul in preparation for divine union.” The picture looks to me like wedding-night stuff; as Hamman says, “To speak of Jesus as lover can feel either cheesy or creepy or somehow, horribly, both. [. . .] It conjures the 1990s and early aughts purity culture inanity of teaching teenage girls that Jesus is their boyfriend until they get married, and then, well, they’ll have a human husband they can finally sleep with.” But she also mentions that many people in the Middle Ages read Christ’s injunction to “take up the cross and abide in me” as carrying simultaneous connotations of both suffering and the bliss of lovers. These concepts were sometimes mingled together in ways it is hard to accept and even understand; as Hamman says, “Following wise ones like Mechthild, or later saints like Teresa of Avila, I understand the layering of the cross and the marriage bed as descriptive, not prescriptive.” Who is right and who is wrong here? Was anyone doing brand control, or giving an official endorsement to this imagery? I don’t know.

Toward the end of the book, Hamman discusses the theme of wounds and uses as an example the famous Isenheim altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald. This painting was made for the Monastery of St. Anthony in Isenheim, which was also a hospital and specialized in the treatment of skin diseases such as plague sores and ergotism. In this painting, Grünewald chose to portray Jesus with plague sores, in a sort of solidarity with the patients at the hospital, who would therefore have seen a Jesus that was just like them, a Jesus who suffered as they suffered, but whose suffering was not without purpose.

With that thought in mind, refer back to Warner Sallman’s Head of Christ. Perhaps the Sallman Christ can take on a new legitimacy—instead of being a myopic and potentially xenophobic refashioning of God in man’s image, the Sallman Jesus becomes instead just one particular cultural group’s envisioning of a Christ who is “just like us,” in the same way that Grünewald painted plague sores on his Christ. It is a historical accident that Warner Sallman painted his picture at a particular time and place, and within a particular cultural context; it is also not his fault that he painted it right at the time when mass communication and manufacturing / marketing at scale would spread his image far beyond its intended audience.

When we depict or describe or imagine Jesus in a particular way, we are of necessity limiting him. Or are we? Perhaps we are merely emphasizing one aspect of his being or personality. Like the blind men groping around the elephant in John Godfrey Saxe’s poem, we each focus on some part of who God is, and then describe him in words or pictures which emphasize that aspect. But doesn’t God himself do this with his self-appellations such as “God Our Righteousness” or “God Who Heals”? However, just because God describes himself in this fashion does not logically imply that we are also allowed to do so. These are very contentious issues, and not only in the Protestant tradition; they have followed the church throughout its history on Earth—recall that it was a dispute over the proper use of images which precipitated the Great Schism out of which came the Orthodox Church.

Images, Picasso famously said, are lies which make us see the truth.1 But is the potential truth worth the possible lie? Any time we try to capture some aspect of God for our own use, we risk going off the mark. “You saw no form of any kind, therefore watch yourselves carefully,” God tells his people through Moses in Deuteronomy2; if we make art that contemplates only one aspect of the divinity, could it be that what we lose is of far more value than what we gain? I’m kind of begging the question here—after all, I’ve gone on record stating my views on the appropriateness of images of the Deity. But if there is anything at all that Grace Hamman teaches me in Jesus Through Medieval Eyes, it is that my own position, informed, as it is, by my Protestant Calvinist religious upbringing, might indeed be too one-sided, and that it behooves me to at least study the perspectives of Roman Catholic and Orthodox Christians regarding the use of images of God.

And by extension—and this is the whole thrust of the argument in Jesus Through Medieval Eyes, the whole thesis—it behooves me to look to all of my spiritual forebears and determine if their perspective has anything to teach me in general. It is very easy, here in my comfortable America, to forget how desperately serious some of these theological positions could become. What would Julian of Norwich, who had herself built into the wall at Norwich Church and lived like that for more than twenty years, have to say about modern Americans’ tendency to go church-shopping or to think of community as just another consumer good? What would the Medieval proponents of suffering think about the modern aversion to pain, risk, or inconvenience of any kind? What would the builders of the cathedrals of Europe think of our willingness to spend lavishly on weddings, vacations, and big screen televisions, yet then build churches which look like little more than community centers or office parks, with little to no decoration or art in them? Who is right and who is wrong in these examples? Do we really think we have figured it all out, that we have a full understanding, and that the past has nothing to teach us? I would hope that the answer to that rhetorical question is obvious.

Although this book is a very easy read, with short chapters that encourage quiet contemplation, it still exhibits a very detailed scholarship, the result of long years of extended study motivated by love of the source material. One thing I often find lacking in books about medieval art is the quality of the illustrations, but this book does not share that fault; a lavish spread of full-color plates reproduces the black-and-white images in the body of the text. Each chapter ends with prompts for further reflection; this is very much a “stop and think” kind of book.

If you feel even the slightest bit wary of considering your own position as normative; if you feel that the Christians of past ages might have something of value to impart to you; if you ever wonder if maybe your own faith tradition might have got something wrong along the way—then I would highly recommend that you find time to read Jesus Through Medieval Eyes. It will, I’m sure, be worth your while.

The actual quote is a little more nuanced: “We all know that art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand.”

Deuteronomy 4:15.

As a committed Catholic and longtime historian: it sounds like Hamman is evaluating pre-Protestant Christianity and finding that it’s...extremely Catholic. There are no themes or depictions here that are scandalous or even unfamiliar to me. This “version” of Jesus never went away! You just won’t find him talked about this way in low-church Protestantism. And it’s telling that--as far as I can tell---the things in these spiritualities that give the author pause are precisely those same Calvinist and Protestant reactions to that earlier “version” of Jesus.

thank you for this excellent review!